Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

This church is dedicated to Sveti Sophia that is the Holy Supreme Wisdom of Christ. It was inspired by the mighty and splendid imperial Cathedral of Constantinople, which was built under the auspices of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (527-565) and was considered one of the most beautiful edifices in the world. Constantinople was a centre of Orthodoxy and of Byzantine art. Each town of any importance had a church built in imitation of the cathedral and even if not a perfect replica, the local church at least had some features in common. For several centuries from the beginning of the eleventh century, Ohrid was the religious centre of the northern part of the Balkan Peninsula. From the ninth century onwards it was the centre of Slavic literature, which began in the time of the Slavic apostles Clemens and Naum. Innumerable works were translated into the Slavic Cyrillic language here.

It is assumed that the original structure of the Sveti Sophia dates from the end of the tenth century, when it served as a cathedral during the reign of the Bulgarian Czar Samuil I, after the elevation of the archbishopric to a patriarchate.[1] During recent excavations in 2002, the foundations of an earlier building were discovered below the north side of the present church.

The church was rebuilt by Archbishop Leo I of Ohrid (1037-1056), the former chartophylax of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. This was a number of years after the fall of Samuil who died in 1018 and before the middle of the eleventh century.

After the defeat of Samuil, his territory was annexed by the Byzantine Empire. Ohrid came under the control of Byzantium again and the religious symbol of Bulgaria’s independence was degraded to the rank of an (autocephalic) archbishopric.[2] Its jurisdiction extended over a vast area. In order to retain its influence over the Macedonian Slavs the court of Constantinople suggested to the Patriarchat of Constantinople that he should appoint as head of the Ohrid archbishopric influential and capable ecclesiastical dignitaries of Greek origin: writers and philosophers, learned theologians and poets. Leo I, who was one of the most outstanding champions of the Orthodox Church in Constantinople, was appointed archbishop. He and the patriarch Michael Caerularius were the leading figures in the dispute within the Church that finally led to the schism of 1054.

It may be assumed that the Sveti Sophia in Ohrid was constructed and ichnographically decorated according to the ideas of Archbishop Leo between 1040 and 1045. The wall paintings in this church indicate the ties the archbishop had with his former seat of Constantinople. They are a manifestation of the glory of that city. It may be assumed that the painters who performed the ambitious work in this church originate from Constantinople or at least from Thessalonica. The simplicity of the drawing and the archaic structure of the forms, the size of the figures and the restricted palette lead to unexpected contrasts of light and dark colours. The firmness of the form and the monumental posture of the saints, also enable us to place these frescoes within the monumental style of this epoch.[3]

The church has survived the centuries, but its appearance now is quite different from the time of Leo I (picture 1).

Picture 1: Church Sveti Sophia, eastern side

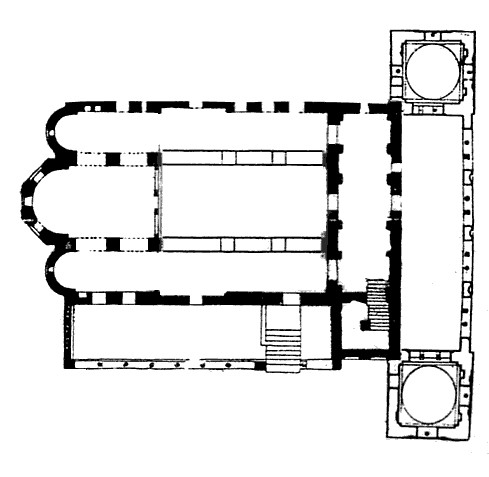

Sveti Sophia was built in the form of a three-aisle basilica with a length of 32 meters. It had a central nave and two aisles each with an apse, a transept, a dome, galleries in the aisles and a narthex (see fig.). It has been suggested that in front of the west facade a high bell-tower was built.[4] Another source, however, has proved that such was out of the question.[5] The church had a stone iconastases with sculptural decorations, a similar ciborium and a decorated stone ambo. In 1313 - 1314 under Archbishop Grigorije I a large exonarthex was added with two domes, together with a hall, galleries and an upper story. The paintings here are dated between 1355-1371. It is remarkable that most depictions of the church show this narthex (picture 2-3).

Picture 2: Church Sveti Sophia, exonarthex

Picture 3: Church Sveti Sophia, outside

About mid fourteenth century the staircase and the chapel of John the Baptist were painted most probably at the order of the despot Jovan Oliver.

The entrance is on the north side after some descending steps. On this side is an open gallery resting on antique columns.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, when the country was under the control of the Turks, the Ohrid Cathedral was converted into a mosque. Significant alterations were made. For example, the dome was demolished and the vault levelled. The Turks removed the iconostasis and its stones were partly used to transform the ambo into a Moslim mimbar. Other relief plates of iconostasis and/or ambo have been found in the floor. A minaret was erected above the north-west dome. All wall paintings were plastered and whitewashed. In the year 1998 new restoration work was started: the mimbar was removed and a new low marble iconostasis was built to separate the naos from the bema. The floor of the church is now covered with marble plates. The church has a double function: it is used as a concert hall and it can also be used for religious services.

The restoration work started in 1951, uncovered the wall paintings. They are considered to be the largest complex of preserved eleventh century Byzantine wall paintings,[6] and are arguably the most important painted works of that period, not only because of their monumental clarity, but also in terms of their thematic content. What has survived is about half of the original wall decorations. Regrettably, the other decorations have been lost in the course of the centuries, due mainly to the measures taken during the Turkish occupation. The remaining compositions have been found in the apse, in the diaconicon and prothesis, on the north and south walls and on the vault. About half of the original decorations from the time of Leo I, have survived. In addition, there are wall paintings in the narthex and Grigorije’s exonarthex, though these are of a later date.

In the literature about the wall paintings in this church experts differ considerably as to the meaning of these paintings. It may, however, be assumed that the paintings from the time of Archbishop Leo I were produced by just one school of artists and by more than one painter, taking into consideration the style of painting, which is somewhat severe and gives an archaic impression. Leo I, who originally came from Constantinople, would have been aware of the religious tendencies in that city. He knew what saints were most honoured in his time, especially in Constantinople, such as the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, John the Baptist and the hierarchs. Is any influence from Constantinople noticeable, or was it the influence of Leo I personally? The majority of experts share the opinion that the wall paintings in the Sveti Sophia are the work of artists from Thessalonica.

Because the central dome was demolished, the most important picture now is in the half dome of the main apse of the sanctuary. It represents Maria seated on a throne and holding an oval shield in both hands before her breast. This shield bears the figure of the infant Christ.[7] The large imposing figure of the Virgin is represented frontally and in majesty (picture 4).

Picture 4: Throning Virgin

A scene like this is called a Maria Platytera. In later years it was also referred to as a Maria Nikopoios, albeit in the latter case it has a different expression. The painting refers to words from Isaiah: “…Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel.”[8] In fact it is an unusual wall painting because it reverts to depictions from before Iconoclasm. This oval shield/mandorla-type is reminiscent of the position which was held by a Nike. In the same way the Nike was wearing the shield with the head of the emperor, Maria holds the shield with the Christ-child. The Nike was ordered to lead the emperor to victory. This task was taken over by Maria. But victory is no longer to the emperor but to Christ, the Pantocrator. [9] The Virgin is dressed in a blue maphorion and sits on a richly decorated lyre-backed throne. Her feet in red shoes rest on a suppedion. The brilliant mandorla in her hands depicts the infant Jesus with the body of a child and the face of a grown-up, representing the doctrine of the two natures of Christ, God and man. He holds a scroll in his left hand, with the other he makes a gesture of blessing. The background of the scene is deep blue like the heavens. The rest of the panorama depicted on the side walls shows the Virgin surrounded on both sides by two rows of five adoring angels (picture 5).

Picture 5: Angels adoring the Virgin

They are approaching with bowed heads, their outstretched arms covered in their himations, in a rhythmical procession equal distance from each other. They are depicted in three quarter pose, kneeling on one knee and one foot forward, making an obeisance in the direction of the Virgin to whom they bring homage. Their wings are thrust into the air. Each of them has a tania in his hair. As is usual with angels they have an androgynous outlook, with a calm and lovely expression on their faces. The linear folds of their clothing indicate the lines and curves of their bodies.

A large and interesting wall painting showing the Communion of the Apostles is on the cylinder of the apse below the enthroned Virgin.[10] Christ officiates the offertory in the centre before the altar. His head is below the ciborium of the altar which rests on four pillars with capitals. His right hand makes a gesture of blessing and in His left hand He holds a round loaf of leavened bread. This is Christ sanctifying and sacrificed (picture 6).

Picture 6: Christ at Communion of the Apostles

There was a dispute in that time about bread to be used in the Eucharist, leavened in accordance with Greek tradition or unleavened (azymes) as became customary in the Roman Catholic Church.[11] During the time of Archbishop Leo I, the Orthodox Church considered the use of unleavened bread a serious transgression in the worship of the Eucharist and the theological influence on this wall painting is clear and unmistakable. Leo I played a leading role in the theological polemic of his time and it is known that he was an adversary of the Roman church. His influence is the reason that Christ holds leavened bread in His hand. The fact that the eucharistic bread was painted suggests that the decorations may have been painted before 1054, the year of the schism, even though the matter of the bread was not the main reason for the schism.[12] Such a scene with leavened bread is unique and is to be seen only on the walls of this church.[13] Christ is assisted by two angels dressed in a white sticharion, who serve as deacons. They hold the liturgical flabella. On both sides six apostles are approaching: on the right side Peter is to the fore; on the left side Paul (pictures 7-8).

Picture 7: Apostles approaching Christ

Picture 8: Apostles approaching Christ

Although the names of the apostles are not mentioned both can be recognised by their physiognomy. The apostles have their hands veiled in their himation in accordance with court etiquette. This was the way to approach the emperor. It is remarkable that only Peter comes nearer with bare open hands. Their respective faces have individual features and the expression on their countenance is severe, as they are aware of the importance of the moment. On the altar stands the stone bottle for the wine.

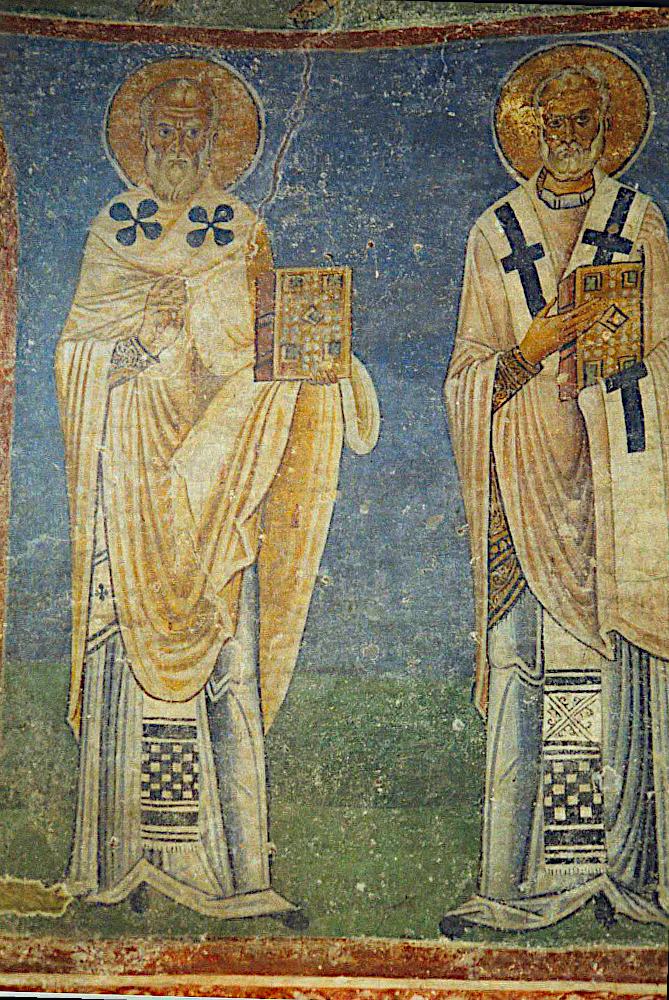

Below this scene a number of hierarchs have been painted between the windows on the apse in the lower zone.[14] They are the earthly witnesses of the Eucharist and underscore its oecumenical character. They belong for the most part to leading fathers of the Eastern Church: from left to right: St. Gregory Thaumaturgos (the Wonder-Worker), St. Gregory of Nazianz (picture 9), St. Ioannes Chrysostomos (picture 10), St. Basil the Great of Caesarea (picture 11), St. Athanasius of Alexandria, and St. Nicholas of Myra (picture 12).

Picture 9: Archbishops Gregory Thaumaturgus and Gregory of Nazianz

Picture 10: Ioannis Chrysostomos

Picture 11: Basil the Great

Picture 12: Athanasius of Alexandria and Nicholas of Myra

The information regarding the life of the hierarchs greatly depends on legends, but some facts are known:

Gregory Thaumaturgus (circa 213-270)[17] was born in Pontus and became a disciple of Origenes, the first bishop of Neocaesarea. He became bishop of Neocaesarea himself in 240. Legend tells that he became known as Wonder Worker. He was a missionary and ecclesiastical writer.

Gregory of Nazianz[18] (329-389) was the eldest son of St. Gregory of Nazianz the Elder. He was a native of Arianzos in Cappadocia. He studied in such important places as Alexandria and Athens where he met Basil. He had set his heart on a monastic life and joined his friend Basil in Pontus. In 361 he was ordained priest, and in 372 consecrated bishop of Sasima, a position he did not like. From 379 he strongly resisted Arianism.[19] For only a short period in 380 he was bishop of Constantinople, but resigned and retired to Arianzos where he died in 389. He wrote a large number of homilies, forty-four sermons, letters and poems. He was one of the important advocates of the Holy Trinity. He is surnamed by the Greeks “the Divine” - o Theologos.

Basil the Great (circa 330-379)[20] was born at Caesarea in Cappadocia. He became one of the three great Oecumenical teachers of the Orthodox Church. After his study at Constantinople and Athens, Basil visited the monastic colonies of Egypt, Palestine and Syria, and founded one himself on the River Iris in Pontus. For this colony he wrote two constitutions, which are still the standard works of their kind for monastic life. In 370 he was made Metropolitan of Caesarea, and at once began his brave fight for orthodoxy against Arians, who had the support of the imperial authorities at Byzantium. Despite this opposition, Basil saved the whole of Cappadocia for the Catholic faith by preaching and writing doctrinal works. He excelled in both of these activities just as he did in the administration of his diocese. His work on the Holy Spirit is still unsurpassed in Catholic theology. He also edited the eucharistic liturgy which bears his name. In the East, Basil is the first of the three Holy Hierarchs; in the West he is regarded as one of the great teachers.

Athanasius of Alexandria (circa 296-373)[21]. History has given this Hierarch titles which he richly deserved: “Father of Orthodoxy”, “Pillar of the Church”, and “Champion of Christ’s Divinity”. He began his public career as a deacon. He denounced Arius as a heretic. He accompanied his bishop to the Council of Nicea, and on his return to Alexandria (328) was made patriarch of that city. There he governed for over forty years. His life-work was the defeat of Arianism and the vindication of the divinity of Christ. For this cause he was five times exiled from his see: in 336 to Trier; in 339-346 to Rome; in 356-362 to the desert; and a second time again to the desert for four months in 363. The year 365-366 was the last of his exiles. Through it all he managed to guide his flock and to write some very illuminating treatises on Catholic dogma for them. One of his most attractive characteristics was his unfailing humour, which often proved an effective weapon against his adversaries. He is revered in the universal church as one of the four great Greek teachers, and in the East as one of the three Holy Hierarchs. He was an outstanding theologian.

Only a few facts are known about St. Nicholaos of Myra (circa 270-342)[22]. But more numerous were the legends that arose about his life. His relics were surreptitiously taken away from his grave at Myra in 1087 by merchants from Bari.

To continue the description of the wall paintings a Deësis is seen on the triumphal arch, Christ in the centre is flanked by the Virgin at the left side and John the Baptist is on the other side. Two angels stand behind them.

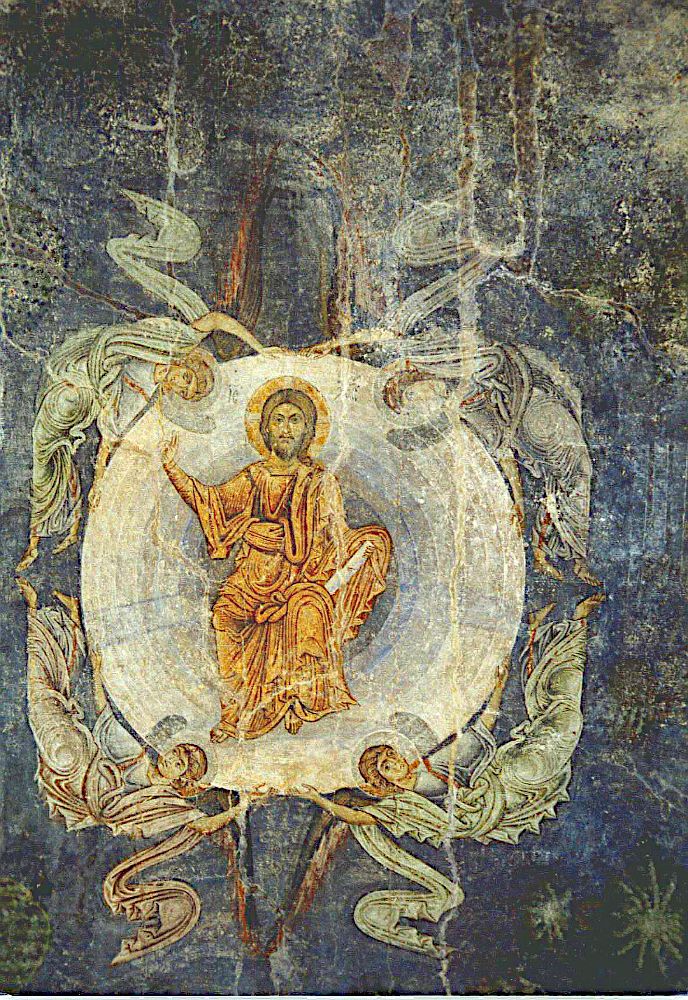

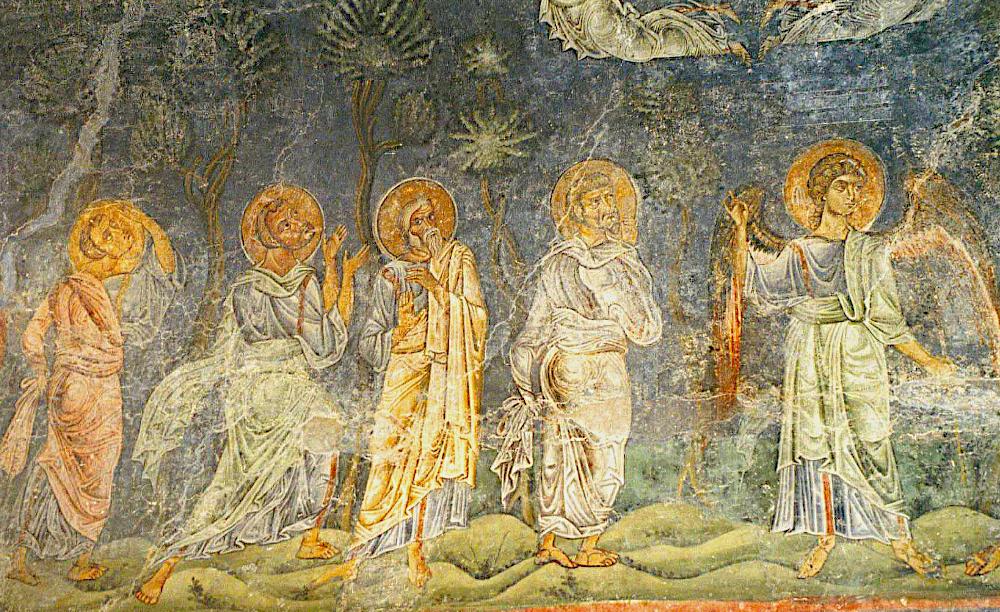

One of the largest well preserved wall paintings from the time of Leo I is the Ascension of Christ or Analepsis on the hemispherical vault of the sanctuary.[23] It is a monumental wall painting, one of the largest of its kind in the Byzantine world and very impressive. A majestic Christ surrounded by a round mandorla sits on a heavenly arch, with his right hand making a gesture of blessing. In his left hand he holds a scroll. He is dressed in a gold-shining chiton with a himation which is partly draped over his left arm. Christ is ascending in glory. Four angels with fluttering himatia fly around the mandorla, their wings stretched out gracefully in northerly and southerly direction, reinforcing the impression of movement and floating. The linear folds of their clothes describe the curves of their bodies. It shows a manneristic lightness of line in the drapery, which is only seen again 150 years later in the Church of Sveti Djordje at Kurbinovo. A blue sky surrounds the group of Christ and the angels, symbolising the light wherein God lives. On each side the apostles are standing in paradise-like surroundings with palm trees. They look upwards to see the King of Glory ascending in the light of his mandorla and their arms are raised in astonishment (picture 13-19).

Picture 13: Ascension of Christ

Picture 14: Ascension of Christ

Picture 15: Ascension of Christ

Picture 16: Ascension of Christ

Picture 17: Ascension of Christ

Picture 18: Ascension of Christ

Picture 19: Ascension of Christ

Most of the scenes in the sanctuary of this church originate in the Old Testament and have an incarnational and eucharistic meaning. The Eucharist is considered to be one of the most important actions of the church and always takes place in the sanctuary. The Sacrifice of Abraham is the Old Testament prototype of the sacrifice of Christ. Abraham, who offered to sacrifice his son Isaac, symbolizes God the Father who will sacrifice his son for the salvation of mankind. The substitute ram that is entangled with its horns in a bramble-bush is a symbol of Christ. The hospitality of Abraham or Philoxenia is symbolically related to the Last Supper. Jacob’s Ladder and the Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace have an eucharistic connection. The wall painting of Basil in which the saint has a vision of Christ making the Offertory and celebrating the first mass is considered to have a corresponding meaning.

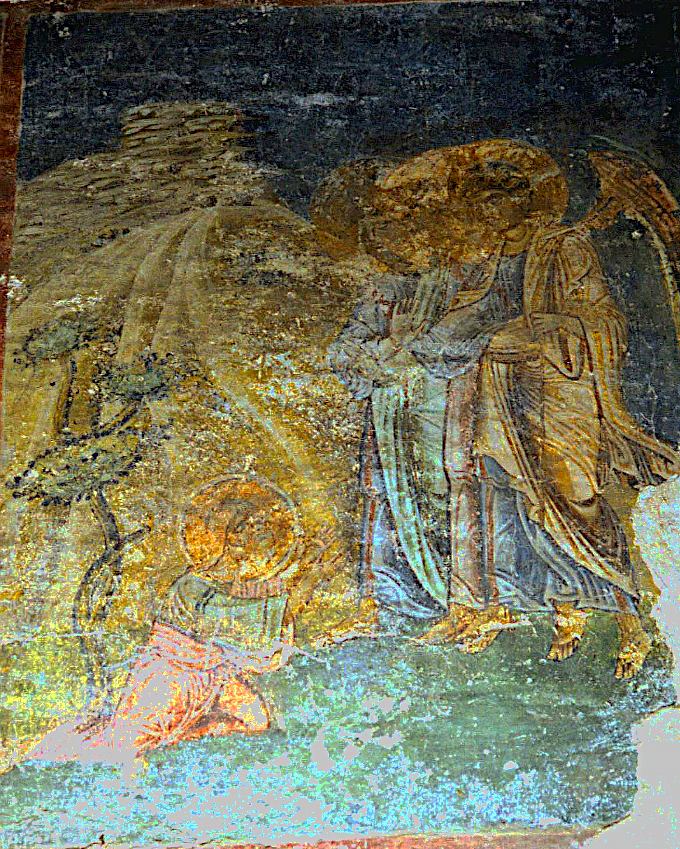

The Philoxenia of Abraham[26] can be seen on the south side of the sanctuary. The wall painting consist of two parts: on the right side three men, here depicted as angels with nimbi and outspread wings, arrive before the tent where Abraham had been sitting. Abraham is shown running to meet them “and bowed himself toward the ground” (picture 20).

Picture 20: Abraham greeting three angels

Scenes like this appear in a number of catacombs, dating from the beginning of Christianity.[27] The second scene has been rather damaged by the attachment to the wall of the Moslim mimbar which was removed in 1998. It shows the three men, sitting behind a table (picture 21).

Picture 21: Philoxenia of Abraham

The man in the centre has a nimbus with a cross and a serene face.[28] According to old Jewish literature the three men are Michael, Gabriel and Raphael.[29] Another source reveals that the three men whom Abraham entertained unawares at Mamre have been identified variously as God, Michael and Gabriel; as the Logos, Michael and Raphael; as the Holy Ghost, God and Jesus.[30] On the left-side wall painting Abraham brings a plate of food he had had prepared. Behind him stands his wife Sarah in the entrance to the tent, which is depicted as the door of a house. From there she peers from behind a raised curtain, listening to the conversation, as recorded in Genesis: “And they said to him: Where is Sarah thy wife? And he said, Behold, in the tent. And he said, I will certainly return unto thee according to the time of life; and, lo, Sarah thy wife shall have a son. And Sarah heard it in the tent door, which was behind him.”

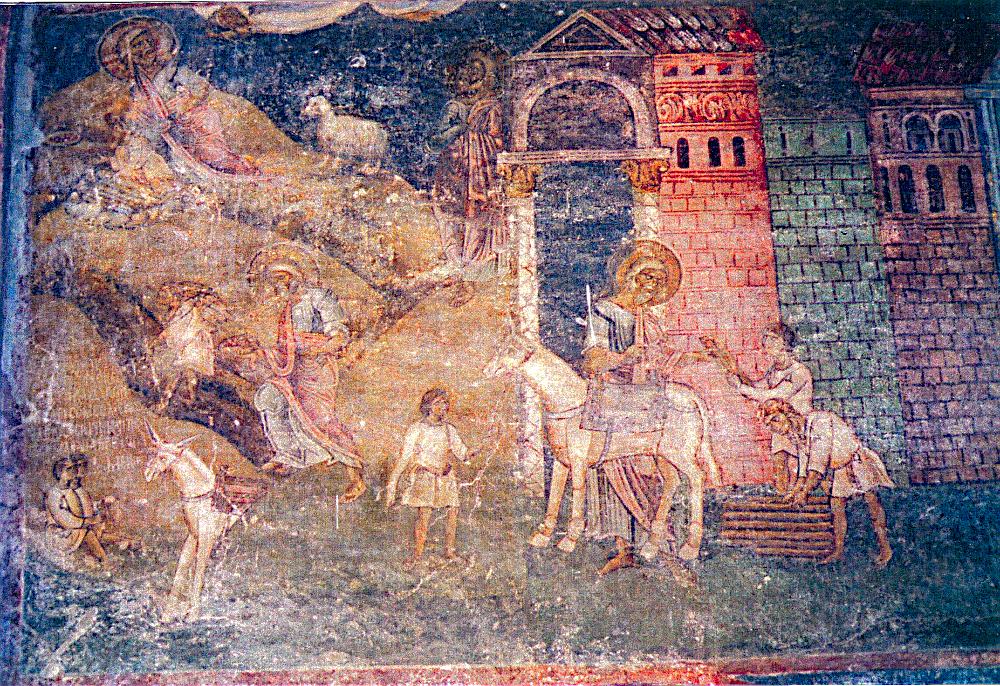

On the left of this scene the Sacrifice of Abraham has been depicted.[31] It is a large scene which has been partly damaged (picture 22).

Picture 22: Sacrifice of Abraham

In the beginning of Christianity this scene was depicted in a number of catacombs.[32] It shows Abraham standing in front of his house. He is busy with two of his servants loading the ass with split wood for the offering. Isaac holds the reins of the animal. The left part of the scene shows a mountainous landscape. The two servants are waiting in the left corner together with the ass. Above their heads an extensive text has been written, most probably containing the story as described in Genesis. Abraham, with Isaac in front of him, is climbing the mountain. They are carrying the wood. On the top of the mountain Abraham is shown intending to sacrifice his only son who is kneeling before the pyre. Below this scene words have also been painted. Abraham turns his head to look up at the hand of God which shows him the substitute white ram. At the other side the hand of God appears for the second time making a gesture of blessing towards Abraham, and beckoning him with a promise to multiply his seed.[33]

On the north side of the sanctuary one can see from right to left in succession the Liturgy by Basil the Great, the Vision of Johannes the Evangelist, the Dream of Jacob with the ladder to Heaven and the Three Hebrews in the burning furnace. Like the wall paintings on the south wall they have a eucharistic meaning or refer directly to the most important acts of the Christian liturgy.

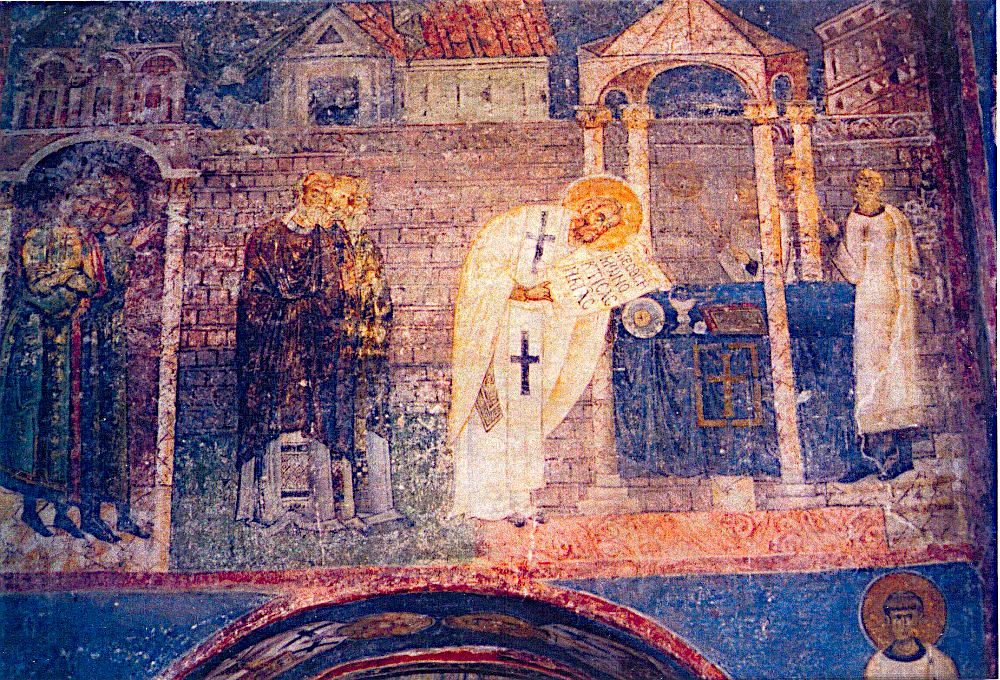

The celebration of the liturgy by Basil the Great of Caesarea is a rare example of illustrations in orthodox churches (picture 23).

Picture 23: Liturgy by Basil the Great

He is assisted by two deacons who stand on the other side of the altar each holding a flabellum. Behind Basil three other bishops are officiating. In the entrance to the sanctuary a number of faithful people are in attendance. Basil holds an unrolled script in his hands which shows a prayer that has a eucharistic meaning. He bows to the Holy table for the prayer of the eucharist. The background shows houses of a town. A loaf of leavened bread with a cross on it is clearly visible on the altar table below a ciborium on four pillars. Next to it stands a bottle for the wine. It is possible that Leo I ordered this scene to be painted for both theological and political reasons. By again showing leavened bread on the altar, he underlined the position attitude of the Eastern Church. It is only in this church at Ohrid that a representation of leavened bread occurs.[34]

To the left of the wall painting of the Liturgy by Basil the Great a fresco can be observed, about which experts hold different views regarding its meaning. The opinion is that the wall painting portrays the Vision of Ioannis Chrysostomos in which Christ, together with Paul and the other apostles, enters his room. Other authors hold that the wall painting represents the Vision of Johannes the Evangelist - Johannes Theologos.[35] In my opinion the latter scene has been depicted here (picture 24).

Picture 24: Vision of Johannes the Evangelist

Depictions from the life of Johannes the Evangelist are rare in Byzantine art. Even though the wall painting is somewhat damaged it is clear that the old bearded saint is lying on a mattress, holding his left hand thoughtfully to his head. Beside and partly behind the bed stands a figure with a nimbus that is difficult to distinguish. He touches the right shoulder of the saint. Just behind this man’s back is the dark opening of a gate of a house, and on the left side there is a mountain. It may be Ephesus where Johannes was living. To the left of the scene a number of people indicated, by their nimbi, are led by two bare-footed men dressed in chiton and himation. They are immediately followed by a third man, who is approaching Johannes the Evangelist. Their faces have been slightly damaged over time so that they cannot be properly distinguished, except for one man in the foreground. This is Paul.[36] The man on the left holds a scroll in his left hand. The two are holding their open hands outstretched in the direction of the saint as if they are asking him for something. A third man is just behind the two men in the foreground, the others are only indicated by their nimbi.

A Syrian legend tells the following story: “And when the Gospel rose upon the world, the Spirit of holiness willed, and Matthew was moved and composed the Evangel; and after him, Mark; and then Luke. And they wrote, and sent (word) to the holy John that he too should write, and informed him concerning Paul, who had entered into the number of the Apostles. But the holy (man) did not wish to write (a Gospel), saying that they should not say ‘He is a youth’, if Satan casts dissension into the world.

And when the Apostles had travelled about in the countries, and had planted the Cross, and it had spread abroad over the four quarters of the world, then Simon Cephas (Peter) arose, and took Paul with him, and they came to Ephesus unto John. And they rejoiced with a great joy, and were preaching concerning our Lord Jesus without hindrance. And they went up to the holy (man), and found him praying. And they saluted one another, and rejoined with a great joy, and narrated to one another all that our Lord Jesus had done, and appointed (as) priests believing men.

Peter and Paul entered Ephesus on a Monday, and for five days they were persuading him, whilst rejoicing, to compose an Evangel, but he was not willing, saying to them, ‘When the Spirit of holiness wills it, I will write.’ And on a Sunday, at night, at the time when our Lord arose from the grave, the Apostles slumbered and slept. And at that glorious time of Resurrection, the Spirit of holiness descended, and the whole place, in which they were dwelling, was in a flame; and those men who were awake, awakened their fellows, and they were amazed. And John took paper, and wrote his Evangel in one hour, and gave it to Paul and to Peter.[37] And when the sun rose, they went down to the house of prayer, and read it before the whole city, and prayed, and partook of the body and blood of our Lord Jesus. And they came to the holy (man), and remained with him thirty days; and then they came to Jerusalem, to Jacob (James), the brother of our Lord, and thence they came to Antioch.

And the holy (man) sat in the hut summer and winter, until he was a hundred and twenty years of age, and there his Master buried him in that place, as Moses was buried on Mount Nebo.”[38] Johannes Theologos is usually depicted in paintings as an old grey man. This concept is most probably developed from the story about his old age; moreover the word of the Lord revealed to him that he should not see death, before he had seen the return of Christ.

It is not quite clear why Leo I commissioned the painting of this scene in the sanctuary, or whether it has a eucharistic meaning. There seems to be no evident reference to a dispute with the Roman Catholic Church which could explain its presence there. A possible explanation is that Leo I originated from Paphlagonia on the north coast of Asia Minor[39] and therefore was aware of the Syriac manuscripts in which the story is related.

Next to this wall painting is a scene called the Dream of Jacob.[40] Young Jacob lies sleeping on the ground. He supports his head with his left hand (picture 25).

Picture 25: Dream of Jacob

In his dream he sees a ladder in front of him based on the earth with the top reaching to heaven. Four angels in different poses are ascending and descending the ladder, in accordance with the text of the Old Testament, the lowest beckons to Jacob to follow him. At the top heaven has been depicted where Christ is waiting. He has been portrayed as the Ancient of Days with white hair.[41]

A dream and a vision beside each other on the same wall can be related to the eucharist. Johannes the Evangelist was resting on the shoulder of Christ. Jacob was dreaming and was blessed by God. In the Sveti Sophia church in Ohrid the paintings have such a meaning. Similarly, the majority of Byzantine depictions of Old Testamentic scenes, when painted in the sanctuary, have such a eucharistic meaning. The basic concept of the sanctuary was always to bring to the fore theological knowledge which could only be understood by well-educated people. In particular the learned bishops loved such themes. This is the reason why these were frequently painted in large cathedrals; Sveti Sophia is a prime example of this theme.[42]

The last painting on the north wall – again partly damaged - is the scene of the Three Men in the Burning Fiery Furnace as has been described in Daniel 3:1-30.[43] In old Christian art it is a beloved theme, which was previously painted in catacombs.[44] Here in particular the scene as described in verses 3:21 to 25 is shown (picture 26).

Picture 26: Three men in the Burning Fiery Furnace

“The men were bound in their coats, their hose, and their hats, and other garments, and were cast into the midst of the burning fiery furnace.” The king said “I see four men loose, walking in the midst of the fire, and they are not hurt; and the form of the fourth is like the Son of God.” A mighty angel with outspread wings keeps his protective arms above and around the three Chaldeans named Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego. They are dressed and each has a hat on his head. Their hands are raised up to their protector at whom they are looking. Below them there is a stone wall with half-round openings, through which the fire-mounds and the flames of the furnace are visible.

The theme of this kind of scene is related to the salvation motif: that is, rescue from death. In particular in this appears in old Christian sepulchral art, again reflected in catacombs. Here in this church it can be related to a eucharistic offering. The suffering of the three men in the furnace is compared to the suffering of Isaac. Both are saved by an angel. It can be related to the sacrifice of Christ who gave His life for mankind.

On the west wall of the naos below the balcony of the narthex, the Assumption of the Virgin, the Koimesis, has been depicted.[45] It is one of the oldest representations of this subject in Byzantine art.[46] The Assumption of the Virgin seems to have been a belief that originated in apocryphal literature from about the fourth century onwards. The death and Assumption of the Virgin Maria, of which there are many accounts in various languages, had a profound effect on Christian theology and practice in both the East and the West. The history of the tradition is largely unknown. Various accounts tell of the death of Maria in Jerusalem. Another source states that it was in Bethlehem to which she returned after visiting the sepulchre in Jerusalem.[47]

The wall painting shows the Virgin lying on a bier, with her head on the left side (picture 27).

Picture 27: Koimesis

Christ, surrounded by a hardly visible mandorla, stands behind the bier amidst a crowd of mourning apostles and some church fathers. He holds the soul of his mother in the shape of a swaddled child on his left arm. A grey Johannes the Evangelist grieves behind the bier on the right side of Christ, his head is close to that of the Virgin. On the left side in front of the bier Peter moves the censer. Behind him stand a number of the apostles and a bishop. At the foot of the bier another group of apostles headed by Paul are mourning. Among them are two bishops.[48] Two angels with veiled hands approach Christ to receive the soul of his mother from him. At the top of the scene at both sides two clouds bring the apostles near. “And the Holy Ghost said to the apostles ‘All of you together mount up upon clouds from the ends of the world and gather at the same time at Bethlehem the holy because of the mother of our Lord Jesus Christ. Peter came from Rome, Paul from Tiberia, Thomas out of the inmost Indies, James from Jerusalem’.”[49]

The wall paintings in the naos suffered the greatest damage during the Turkish occupation. On the south wall there is a painting representing the birth of Maria (picture 28) the right side of the wall painting is in a poor condition.

Picture 28: Birth of Maria

Anna is lying on a bed. A servant is bringing her food. The swaddled figure of Maria is lying in her cradle. The background behind Anna shows a large house.

On the north side of the aisle a fragment of a wall painting has been preserved. It shows the Presentation of Maria in the Temple in fulfilment of a promise by her mother.[50] The fragment shows Joachim and Anna presenting the young three year old Maria to the priest in the temple. The colours of the wall painting are faded. The same applies to the painting of the Birth of Christ and of the Baptism. In the first one Maria can vaguely be seen lying on a mattress and the two midwives are bathing the child. The Baptism panel probably consists of two parts. On the left side, Christ is approaching and talking to some people while on the right side he is standing in the water of the river about to be baptised (picture 29).

Picture 29: Baptism of Christ

It is a remarkable fact that there is a young boy - most probably the personification of the river - also in the water who is bowing deeply towards Christ.

Beneath this wall painting two archangels have been painted on each side of the door leading to the narthex. On the right side the Archangel Gabriel stands with large outspread wings, holding a staff in his right hand and a globe or disc in his left[51] (picture 30).

Picture 30: Archangel Gabriel

He apparently stands there as a watchman. He is dressed in a chiton and a himation. The chiton is decorated. On the other side stands Michael. This wall painting is in bad condition.

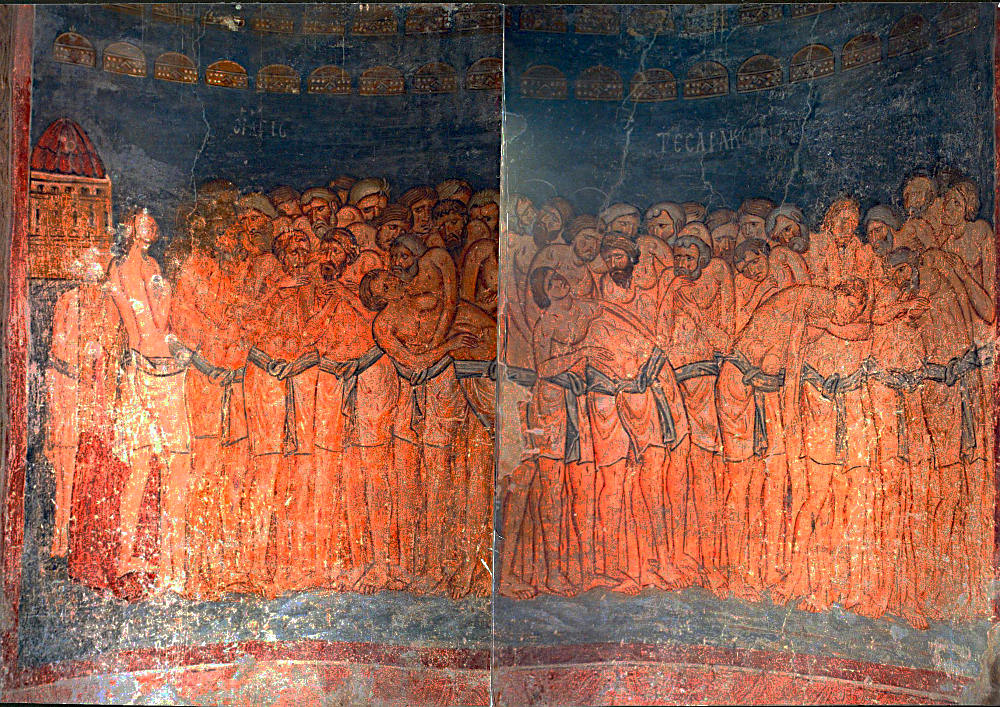

In the apse of the prothesis the scene of the Forty-Martyrs of Sebaste has been illustrated[52] (picture 31).

Picture 31: Forty Martyrs of Sebaste

A window in the middle of the apse divides the group into two parts. The scene was a popular theme in Constantinople, the town from which Leo I came. According to the story, the men, soldiers in the Roman army under Licinus at Sebaste in Armenia, had confessed to being Christians. They were condemned to martyrdom, and dressed only in a loin-cloth, they were left to freeze to death on a frozen lake. One of them retracted his confession and in most portrayals he is seen departing through the door of a warm bathhouse. The story goes that the gatekeeper, a proselyte who had also accepted Christianity, took his place. Later their frozen bodies were burnt and their ashes and bones thrown into the water of the river. The story continues that Bishop Petros of Sebaste collected the bones from the water. The wall painting in the prothesis shows two groups of men covered only with a loin-cloth. Remarkably, those forty men did not die namelessly. History has given them names.[53] Their faces express their pain and the painter has detailed the martyrs’ movements and their reactions. Some of them support a desperate comrade who can hardly bear the punishment. In the left part of the scene, a building, the bathhouse, has been painted. The proselyte comes from there to join the others. The back of the man who is retracting is seen inside the door. Above their heads forty martyr-crowns have been painted. The size of the wall painting denotes its importance as a most celebrated theme. The unknown artist(s) has/have paid great attention to the reactions and individual expressions of the martyrs.

On the south wall of the prothesis above the arches, a long wall painting of poor quality can be seen. It shows the collecting and burial of the martyrs’ bones. Some men and a horse-drawn cart can be distinguished.

In the diaconicon, but also in the prothesis, the naos and in the arches separating the nave from the aisles a surprisingly large number of patriarchs, bishops, theological writers and other dignitaries has been portrayed. This large number could indicate that the archbishop of Ohrid, Leo I, had regular direct contact with ecclesiastical authorities in Constantinople and via them perhaps directly with Rome. Patriarchs from Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem, bishops from Asia Minor and archbishops from Cyprus are shown on the wall in the naos. With his own Paphlagonian origin in mind he had the bishops from Asia Minor also painted in prominent places.[54] It is remarkable that the figures of at least six popes of the Roman Catholic Church have been painted, because popes were not usually honoured in Eastern churches, although there are some exceptions. Presumably these papal portraits predate the letter of 1052 sent by Michael Caerularius, Patriarch of Constantinople, and Archbishop Leo of Ohrid to John, bishop of Trani, which precipitated the schism between the Eastern and Western churches in 1054.[55] In the apse can be seen: Pope Innocentius, Pope Vigilius, Pope Clemens I (picture 32), Pope Leo I, Pope Gregory the Great Dialogos and Pope Sylvester I (picture 33), respectively, although it is not definite that the first one is indeed Innocentius.[56]

Picture 32: Popes Innocentius, Vigilius and Clemens

Picture 33: Popes Leo I, Gregory the Great and Sylvester I

The last three are clearly mentioned by name. The name indication of the other three has disappeared in the course of time. It is suggested that they have been depicted in the apse because in former times they were the believers in an ecclesiastical unity. All six are dressed in the same way, wearing a phelonion, with three large crosses on the omophorion. Each of them holds a richly decorated evangelarium in his left hand. They are tall, standing figures, painted frontally, with a fixed view in their faces. The only difference is their individual expression and the way in which they position their right hands. Two make a gesture of blessing, while the others are pointing at the book they hold in their hands.

Of particular significance on the south wall of the diaconicon near the iconostasis is the presence of the Slavic educators, Cyril and Methodius [57]and of their most noted disciple St. Clemens of Ohrid, better known as Sv. Kliment[58] (picture 34).

Picture 34: Cyril and Methodius and Clemens of Ohrid

Even though the wall painting is damaged, it is clearly visible that they are dressed in the same way as the popes. They each hold an evangelarium in their hands as well. The presence of these portraits in the cathedral church of the Ohrid archbishops is one of the strongest confirmations that their cult was widespread in Macedonia during this period.[59] The portraits were undoubtedly included in the theological decoration of the cathedral on the orders of Leo. He may have been acting out of political expediency with regard to the Macedonian Slav faithful, who followed this cult. He thereby established his own policy, as well as that of the official church towards the patrons of the Slavs.[60] The appearance in this church of the figures of St. Cyril and St. Methodius, and of their disciple St. Clemens of Ohrid, played an important role in the later development of portraits of these saints in medieval art in Macedonia and elsewhere in this part of the Balkan Peninsula.[61]

On the northern pillar looking westward a fragment shows the Virgin holding the Christ-child in her arm. It is notable that the child has bare legs to the knee (picture 35).

Picture 35: Maria with the Christ child, fragment

It may be that this was done intentionally to express the human side of the Christ-child. This concept is only seen again in the thirteenth century in Toscana.[62]

On the southern pillar a fragment reveals the Virgin holding the Christ-child in her lap. The child in a golden himation makes a gesture of blessing with his right hand and holds a scroll in his left hand. Both are looking forward. (picture 36).

Picture 36: Maria with the Christ child

Leo I had a large number of bishops painted on the walls of this church. Not all can be identified. In some instances the names have disappeared.[63] Some of them have been depicted in full length (picture 37), while others, like Bishop Polykarpos of Smyrna (picture 38) have been depicted in half length in the corridor to the prothesis.[64]

Picture 37: Bishops

Picture 38: Bishop Polykarpos of Smyrna

This saint is said to have been converted by Johannes the Evangelist about the year 80. Polykarpos, together with his friend, St. Ignatius of Antioch and their disciples, were the link between the apostles and subsequent generations of Christians in Asia Minor. Because of his faith, Marcus Aurelius ordered him to be burned to death. The flames failed to hurt him so he was stabbed with a sword.

The vault of the diaconicon originally contained a number of scenes relating to the life of John the Baptist. Only some have been partly preserved.

The narthex was completed and extended under Archbishop Grigorije I in 1313 - 1314. It is one of the most beautiful examples of Byzantine and Macedonian architecture of the fourteenth century[65] (picture 2-3).

Picture 2: Church Sveti Sophia, eastern side, exonarthex

Picture 3: Church Sveti Sophia, eastern side, exonarthex, outside

Two domes and a hall were added together with a staircase at the north side which leads to the gallery upstairs. The latter consists of two parts. There is a large room in the middle which is open at the side toward the church. On the other side there is an open gallery. Archbishop Grigorije I was a writer and politician who enjoyed the utmost confidence of Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus and his chancellor Theodore Metochitus.[66] The archbishop is particularly known for his poems dedicated to Kliment of Ohrid.

On the vault of the original narthex and on the walls, there is another group of eleventh century wall paintings, containing a large number of female saints. One of the largest collections is painted between the groins on the vault. Unfortunately hardly any names of these female saints have been preserved (picture 39).

Picture 39: Female saints

On the wall above the entrance of the staircase there is a wall painting not seen very often in Orthodox churches. It is a depiction of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus[67] (picture 40).

Picture 40: Seven sleepers of Ephesus

Their story, which is based on an old legend, is known in the Orthodox Church, by the Copts and Armenians, in the western church and in the Islamic world. Seven boys who worked as shepherds were hiding in a cave during a persecution by the Roman Emperor Decius, but they were found and the cave was sealed off with a wall. About 200 years later, during the reign of Theodosius II, they were found and they woke up. In Byzantine art the scene is usually depicted with the young people lying asleep in a cave. The scene is understood to be an evidence for belief in the resurrection. The wall painting shows six youngsters sleeping in the same position. All are leaning to the left, except on the left side, where one young man leans in the opposite direction. The background is the dark hollow of a cave. They have been given names, but these differ depending on the sources, both in the east and the west. The Painter’s Manual names them as Maximilianus, Iamblichus, Martinianus, Dionysius, Antony, Exacustodianus and Constantine.[68]

Above the staircase there is a chapel consecrated to John the Baptist. The painting of it was ordered by a despot named Jovan Oliver in about the year 1347. It contains portraits of Oliver and his family as well as a depiction of John the Baptist as an angel, holding his head under his arm [69](picture 41). The condition of these wall paintings is not very good.

Picture 41: John the Baptist as angel

The first floor of the narthex was painted in about 1340-1345 and finished about ten years later.

The large room on the first floor contains a number of interesting wall paintings from that period. It is remarkable that less attention has been paid to the wall paintings of that part of the church, because a number of them are rather exceptional in Byzantine wall painting. Maybe they are overshadowed by the older wall paintings from the eleventh century, to which relatively more attention is paid in literature.

On the vault are remnants of wall paintings relating to the Seven Oecumenical Councils. The structure of the paintings here is basically the same. The upper part shows the emperor with the most important holy fathers, whose views prevailed at the council, while the bottom part, depicts the confrontation of orthodox winners and condemned heretics.[70] Most of the wall paintings are in very bad condition. However, two are of special interest. They represent the first and the second Oecumenical Councils. The first Oecumenial Council was held in Nicaea in 325 and was presided over by Emperor Constantine the Great (picture 42).

Picture 42: First Oecumenical Council

This wall painting can be found at the northern side of the room. The lower part, although partly damaged in the left corner shows two groups of bishops. The first bishop of the left group has raised his hands towards the second group. It has been interpreted that the first group represents the bishops who condemned Arianism, while the second group are the supporters of the priest Arius. On the wall between both groups a long text has been painted (picture 43).

Picture 43: First Oecumenical Council, detail

The second Council was summoned by Theodosius the Great (379-395) and held in Constantinople in 381. It is said that the emperor did not join the Council himself.

This wall painting, although somewhat damaged, also shows a number of bishops sitting in a semi-circle headed by the emperor. It has been painted at the southern side of the room. On both sides of Theodosius two young men have been pictured (picture 44).

Picture 44: Second Oecumenical Council, detail

Although no names are mentioned it may be supposed that they are the two sons of Emperor Theodosius: Honorius and Arcadius. It was under the reign of this emperor that Christianity became the official state religion in 384 and a number of years later the pagan religions were forbidden. The emperor decided that after his death the Roman Empire should be divided into two parts, each reigned over by one of his sons; Honorius became the emperor of the West Roman Empire and Arcadius of the East Roman Empire, only later referred to as the Byzantine Empire. The Council Theodosius presided over, was of great importance for the Christian belief, because it was here the theologians formulated the basic Creed recited in the majority of Christian churches today, that of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Related to this series is the wall painting on the south side above the mullioned window showing the vision of Peter of Alexandria.[71] Peter saw a vision of the Christ-child who revealed to him that the thoughts of Arius were not correct.

Another interesting wall painting on the northern wall not seen in other churches, is the so-called David’s Repentance (picture 45).

Picture 45: David’s Repentance

It relates to the story of David and Bathsheba whom he had seen washing herself.[72] He later ordered that her husband Uriah should be placed in the combat zone of the fiercest battle in order that he should be killed. “And when the mourning was past, David sent and fetched her (Bathsheba) to his house, and she became his wife…” The wall painting shows an empty throne. David is kneeling before the Prophet Nathan who informs him that the child he procreated with Bathsheba shall die as a punishment for his sin. Behind the throne stands the personification of Wisdom. Two angels are standing around the throne. The one on the right has drawn a long sword to threaten David with the punishment of God, but the personification of Wisdom stops him.[73] One of the oldest examples of David Repenting can be found in The Paris Gregory from the ninth century and in the Utrecht Psalter.[74]

Another series of wall paintings can be found in the so-called Grigorije’s Gallery, or the open gallery. These are estimated to have been painted between 1355 and 1371. Although they are partially damaged it is plain that they represent the Old Testament story of Joseph, the son of Jacob, who was sold by his brothers to an Egyptian slave-trader and who later became the governor of Egypt under the pharaoh.[75] It is one of the most extensive illustrations of the story in medieval Eastern and Western art.[76] The cycle of pictures starts with a heavily damaged wall painting showing the Dream of Joseph (picture 46).

Picture 46: Dream of Joseph

In the left corner, on the east wall, one can see him lying under a kind of canopy telling his brothers of his dream about the corn-sheaves and the stars bowing to him.[77] The next scene shows how he was sold to an Egyptian slavetrader (picture 47).

Picture 47: Joseph sold to slave traders

This scene is followed by the marriage of Joseph to Asenath, the daughter of Potiphera, who was a priest of On, then follows Joseph’s appointment as governor. The famine that had stricken Egypt was also bad in the area where his family lived. They had purchased corn from Egypt but when it was consumed Jacob asked his sons to go to Egypt again to buy more food. They took Benjamin with them. The next scene shows the story of Joseph’s silver cup which was found in Benjamin’s sack and the subsequent arrest of the group. Joseph in turn made himself known unto his brethren. This is the subject of the next wall painting. The story is too long to relate further in detail here, but one of the last wall paintings shows the meeting of Joseph and his father Jacob. The last scene shows Jacob’s death as the paradigm of a just earthly life. Joseph and the fate of the soul is a rare series in wall painting. The separation of the soul from the body is illustrated extensively. The soul, shown as a small naked child, will be released at the end of its journey from the infernal torments and sufferings through which it has passed. The first known example was painted in the small Church St. Nicholas at Varoš in the year 1298, by an unknown provincial artist.[78] Another example has been discovered in the Chilander Monastery at Athos, in the tower of St. George.[79]

In the same gallery a number of saints have been depicted, as well as Christ Pantocrator on the eastern wall. Regrettably much has disappeared from this open gallery or is in very bad condition, partly because of the effects of the weather. One of the best preserved is a Deesis on the eastern wall with a very thin John the Baptist (picture 48).

Picture 48: Deesis

The bishop on the right is Archbishop Nikola, who commissioned the wall paintings.

Partially hidden is a wall painting that can be found on the wall that is under the first floor of Grigorije’s Gallery. Between the floor and the wall there is a small opening revealing part of what was most probably the original wall of the church, before the extended narthex was built. On it is a wall painting of the Sacrifice of Abraham. He is seen kneeling before the pyre in a mountainous landscape. In one hand he holds a knife, and in the other he holds his child. He is looking around to an angel that is flying nearer (picture 49).

Picture 49: Sacrifice of Abraham

In style it belongs to the Comnenian or late Comnenian art.

Not all wall paintings in this church have been discussed here or described in detail. More can be found in some dark corners. A large number of names of the bishops on the walls of the church have disappeared. Those who have been identified are of less importance and it is of little value, in my opinion, to mention all the names. Most of the panels showing the feasts of the Dodecaorton on the walls of the church have disappeared. The few left are in too bad a condition to describe. The lower and upper narthex and the gallery do contain a large number of wall paintings as well. Only the most important of these have been discussed here. A lot of them are in poor condition. The paintings in the old church can be dated around the year 1040 to 1045. It is generally assumed that they reflect the ideas prevailing at that time in Constantinople. Whether there is any influence from the previous period of Samuil is doubtful.

The paintings in the narthex were applied at different times. A number of the depictions of female saints in the lower narthex are also from the eleventh century, but most are from the fourteenth century. These can be considered to belong to the Palaeologen style of painting, even though they were not done by great masters but most probably by local artisans.

The many depictions of archbishops and popes on the walls prove that Leo I had frequent regular contact with ecclesiastical authorities and that he has honoured the defenders of orthodoxy by depicting them on the walls of this church. The choice of scenes on the walls of the bema is remarkable for their incarnational and eucharistic meaning. The work indicates the ties the archbishop had with his former seat of Constantinople.

Beckwith, p.237; Antoljak, p. 98, is of opinion that the Ohrid Archbishopric was never referred to as a patriarchy, but only as an archbishopric, with note ↑

Obolensky, p.210 ↑

Balabanov, p. 38 ↑

Djurić, Sophia, p. 11 ↑

Schellewald, p. 100-101 ↑

Stewart, Cecil, Serbian Legacy, London, 1959, p.55-57 gives a short review of the problems to be solved, especially the erection of the southern wall which was leaning outwards some two feet. ↑

Wellen, G.A. in LCI 3, s.v. Maria, Marienbild, I B 3f-Maria mit Christusbild in Mandorla (p.160); Hallesleben, H. in ibid -II B 1) thronende Maria mit Kind (p.162). ↑

Isaiah 7:14 ↑

Wellen, G.A. in LCI 3, I B 3f- Maria mit Christusbild in Mandorla (p.160). ↑

Wessel, K. in RbK I, 1966, p.239-245, s.v. Apostelkommunion; Lucchesi Palli, E. in LCI 1, p.173-176, s.v. Apostelkommunion. ↑

Ware, p.66; Smith, Mahlon, H., And taking bread … Cerularius and the Azyme Controversy of 1054, Paris, 1978 ↑

There was a struggle for power between the increasing influence of the popes in Rome and the Byzantine Orthodoxy. Rome pretended preference above all other churches. The azyme question was at best the inducement. ↑

Djurić, 1976, p.10 ↑

Chatzinikolaou, A. in RbK II, p.1034-1093, s.v. Heilige: in particular p.1038ff: B. Die verschiedenen Hl.-Gruppen. ↑

Chatzinikolaou, A. in RbK II, p.1041 “Sie stehen unbeweglich mit starren Blick, welcher die innere Spannung ausdruckt u. Ehrfurcht einflöszt. In die kirchlichen Hierarchie nehmen die Hierarchen den ersten Platz nach den Aposteln ein, insbesondere nach dem Bilderstreit”. ↑

Papas, T., Studien zur Geschichte des Messgewänder im byzantinischen Ritus, München, 1954; Thierry, N., “Le costume épiscopal byzantin du IXe au XIIIe siècle d'après les peintures datées”, Revue des études byzantines, 24 (1966); Walter, C., “Pictures of the clergy in the Theodore Psalter”, Revue des études byzantines, 31 (1973); Chatzinikolaou, A.,in RbK II, p.1048, s.v. (f) “die Gewänder der Hierarchen”; Kuder, U. in LCI 5, p.403-415, s.v. Bischöfe, heilige. ↑

Detzel II, p.398; Réau, III/2, p.606, Chatzinikolaou, A. in RbK II, p.1034-1050, Book of Saints, p.255; Ritter, A.M. in LCI 6, p.453-454, s.v. Gregor der Wundertäter (Thaumaturgos). ↑

Detzel I, p.396-397; Réau III, p.607-608; Chatzinikolaou, A. in RbK, II, p.1034-1050; Knoben, U. in LCI 6, p.444-450, s.v. Gregor von Niazanz, der Theologe; Timmers, p.261; Book of Saints, p.252 ↑

Kretschmar, G., Studien zur frühchristlichen Trinitätstheologie, Tübingen, 1956; Ware, p.29-30; Wiles, M., Archetypal heresy: Arianism through the centuries, Oxford, 1996; Barnes, M.R., Williams, D.H., Arianism after Arius: essays on the development of the fourth century trinitarian conflicts, Edinburgh, 1993; Gregg, R.C., Groh, D.E., Early arianism: a view of salvation, London, 1981; Gwatkin, H.M., Studies of arianism: chiefly referring to the character and chronology of the reaction which followed the Coucil of Nicaea, Reprint of 2nd edition of 1900, New York, 1978. ↑

Réau, III, p.185-186; Morawa, C. in LCI 5, p.338-342, s.v. Basilius der Grosze; Chatzinikolaou, A. in RbK, p.1034-1050; Book of Saints, p.79. ↑

Detzel II, p.171-172; Réau III, p.145-146; Chatzinikolaou, A. in RbK II, p.1034-1050; Myslivec, J. in LCI 5, p.268-272, s.v. Athanasius der Grosze von Alexandrien; Book of Saints, p.64-65; Timmers, p.236. ↑

Réau III, p.976-988; Chatzinikolaou, A. in II, p.1034-1050; Petzoldt, L. in LCI 8, p.45-58, s.v. Nikolaus von Myra (von Bari); Book of Saints, p.416; Timmers, p.287, s.v. Nicolaas van Myra; fora n extensive description of his miracles, see Chapter XV, Sveti Demetrius church. ↑

The Acts 1:9-12, also Mark 16:19; Luke 24:51; Lit. Wessel, K. in RbK II, p.1224-1262, s.v. Himmelfahrt; Pallas, D.I. in RbK III, p.13-119, s.v. Himmelsmächte, Erzengel und Engel; Schiller III, p.140-164, s.v. Die Himmelfahrt Christi; Schmid, A.A. in LCI 2, p.268-276, s.v. Himmelfahrt Christi. ↑

The Acts 1:11 ↑

Ps.23 (24) and the Ascension of Christ in Chludov-Psalter fol. 22r. in Hist. Mus. Moscow ... “Below Christi Gloriole lies David in Proskynese”; Wessel, K. in RbK I, p.1145-1161, s.v. David, C 8 “David is bei Christi Himmelfahrt anwesend”; ibid in RbK II, p.1224-1262, s.v. Himmelfahrt II f, p.1254; Wyss, R.L. in LCI 1, p.477-490, s.v. David, 2) In Gruppen b) David ist Zeuge bei der Himmelfahrt Christi anwesend, Vat.gr. 1612 fol. 2v. ↑

Genesis 18:1-15; Wessel, K. in RbK I, p.11-22, s.v. Abraham, B: Die Philoxenie; Lucchese Palli, E. in LCI 1, p.20-23, s.v. Abraham. ↑

Ferrua, fig. 49; Schubert, U., Studia Judaica Austriaca II, p.11-34, s.v. Nr. 4 Abraham und die drei Engel in Mamre. ↑

Tatić-Djurić, M., Das Bild der Engel, Recklinghausen, 1962, p.23: “In den alttestamentlichen Schriften wird das Wort Engel gelegentlich auch als Synonym für Gott verwendet, und die Bezeichnungen wechseln ohne genügende Motivierung.” op.cit. ↑

Lueken, W., Michael, Eine Darstellung und Vergleichung der jüdischen und der mogenländisch-christlichen Tradition vom Erzengel Michael, Göttingen, 1898, p.33: “Unter den drei Männer, die zu Abraham kamen, nahm Michael den Ehrenplatz, den Platz in der Mitte zwischen Gabriel und Raphael, ein. ... Gabriel rechts, Raphael links von ihn.” op.cit. ↑

Davidson, G., A Dictionary of Angels, New York/London, 1967, p.289 - It might not be out of place to recall a Greek parallel recorded by Ovid: three of the chief Olympians (Zeus, Poseidon, Hermes) were guests of Hyrieus, an old man of Tanagra. In David’s version, bidden by the gods to express a wish, the old man, being childless, asked for a son. The wish was granted. The son was Orion. ↑

Genesis 22:1-19; Lucchesi Palli, E. in LCI 1, p.20-35, s.v. Abraham. ↑

Bourguet, picture p.37 in the catacomb of Priscille; Ferrua, fig.68 and 113; Schubert, U., Studia Judaica Austriaca II, Wien, 1974, p.11-34, i.p. Nr.5 Opferung Isaaks. ↑

Genesis 22:15-18 ↑

Djurić, 1976, p.10 ↑

Nilgen, U., in LCI 1, p.696-713, s.v. Evangelisten; Lechner, M. in LCI 7, p.108-130, s.v. Johannes der Evangelist (der Theologe); Timmers, p.269-271; Book of Saints, p.317. ↑

Painter's Manual: The twelve apostles and their characteristics: Paul, bald, with a brown, rush-like beard. ↑

In another version it is said that John dictated the Evangel to Prochoros and that three evangelists asked John to write a Gospel. ↑

Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, edited from Syriac manuscripts in the British Museum and other libraries, by William Wright, with English translations and notes, London, 1871, part 2, The History of John, the son of Zebedee, p.58-59, op.cit. ↑

Djurić, p. 11 ↑

Genesis 28:12-15; Lit: Wessel, K. in RbK III, p.519-525, s.v. Jakob; Kauffmann, C.M. in LCI 2, p.370-383, s.v. Jakob. ↑

Daniel 7:9; Lit: Lucchesi Palli, E., in LCI 1, p.390-399, s.v. Christus-Sondertypen, 3) Christus - Alter der Tage. ↑

Djurić, 1963, p.IV. ↑

Ott, B., in LCI 2, p.464-466, s.v. Jünglige, Babylonische; Wessel, K. in RbK III, p.668-676, s.v. Jünglinge im Feuerofen. ↑

Bourguet, p.25; Ferrua, fig.41 and 144. ↑

Wratislaw, L., Okunev, N., “La Dormition de la Sainte Vierge dans la peinture médievale orthodox”, Byzantinoslavica, 3 (1931), p.134-174; Weitzmann, K., “Das Evangelion im Skevophylakion zu Lawra”, Seminarium Kondakovianum, 8 (1936), p.83-98, reprinted ibid, Byzantine Liturgical Psalters and Gospels, London, 1980, article nr. XI; Jones, E.M., “The Iconography of the Falling Asleep of the Mother of God in Byzantine Tradition”, Eastern Churches Quarterly, 9, 1951/52, p.101-112; Gaviloff, M., “The Dormition and Assumption of the Blessed Virgin in Slav Iconography”, Eastern Churches Quarterly, 9, 1951/52, p.113-119; Jacobs, A., “Het ontslapen van de Moeder Gods in de Ikonografie”, Het Christelijk Oosten, 19, 1966/67, p.65-72; Scaffer, C., Koimesis, Der Heimgang Mariens. Das Entschlafungsbild in seiner Abhängigkeit von Legende und Theologie, Regensburg, 1985, esp. p.59-95; Schiller IV, p.83-114, s.v. Der Tod Marias und ihre Verherrlichung; Kreidl-Papadopoulos, K.in RbK IV, p.136-182, s.v. Koimesis; Myslivec, J. in LCI 4, p.334-338, s.v. Tod Mariens. ↑

Grozdanov, Cvetan, Sveti Sophia Ohrid, p. 38 ↑

Elliott, p.691 s.v. The Assumption of the Virgin; ibid, p.701, s.v. The discourse of St. John the Divine concerning the falling asleep of the holy Mother of God. ↑

Paint.Man., note 9 to p.50, states among others that the chief source for the depiction of three bishops is found in the “De Divinis Nominibus” of Dionysius pseudo-Areopagite; although this was interpreted by St. John Damascene to mean that there were four bishops present at the Koimesis, three had become the standard number by the twelfth century, with only very rare exceptions. According to Paint.Man. p.50, the bishops Dionysius the Areopagite, Hierotheus and Timothy should be around the bed. ↑

Elliott, p.702, verse 12 ↑

Elliott, “The Protevangelium of James”, ch.6:1 and ch.7 ↑

Lucchesi Palli, E., in LCI 1, p.674-681, s.v. Erzengel; ibid in LCI 2, p.74-77, s.v. Gabriel; Tatić-Djurić, M., Das Bild der Engel, Recklinghausen, 1962. ↑

Chatzinikolaou, A., in RbK II, p.1034-1063, s.v. Heilige, B.II.e: Hl. Soldaten-Die Vierzig Martyrer (p.1059-1061); Hochenegg, H. in LCI 8, p.550-554, s.v. Vierzig Martyrer von Sebaste. The eldest known scene has been depicted in Santa Maria Antique at Rome of about the year 700. ↑

Paint.Man. p.58/59 with note mentions 39 names; see also Kaster, K.G. in LCI 8, p.550/1, s.v.Vierzig Martyrer von Sebaste. ↑

Djurić, p.10-11; Paphlagonia is a historical landscape on the north coast of Asia Minor, bordering in the west to Bithynia and in the south to Galatia. It was added by the Romans to the province Galatia. ↑

Beckwith, p.237. ↑

Tschochner, F., in LCI 7, p.387-389, s.v. Leo I der Grosze ist einer der wenigen Päpste, die auch in der Ostkirche dargestelt werden. ↑

Tachios, Anthony-Emil, Vyril and Methodius of Thessalonica, the acculturation of the Slavs, Thessaloniki, 1989; Myslivec, J. in LCI 6, p. 23-26, s.v. Cyrillus (Konstantin) und Methodius, Apostel der Slaven. ↑

Knoben, U. in LCI 7, p. 324-325, s.v. Klemens von Ochrid ↑

Balabanov, 1995, p.36, op.cit.; Hamann-Mac Lean in the lay-out of the wall paintings in this church does not mention them. ↑

Balabanov, p.37 op. cit. ↑

Balabanov, p.37 op. cit. ↑

Djurić, p. 11 ↑

Hamann, Plan 1-4 Ohrid Sophienkirche mentions the names so far as they could be deciphered. ↑

Weigert. C., in LCI 8, p. 219-220, s.v. Polykarp von Smyrna; Book of Saints, p. 462, s.v. Polycarp of Smyrna and Comp. ↑

Grozdanov, Cvetan, Sveti Sophia Ohrid, Zagreb, 1988, p. 42 ↑

ibid, p. 42; Theodore Metochites was the founder of the Chora Church in Constantinople, see Underwood, Paul A, The Kariye Djami, New York, 1966, vol. 1, p. 27-28 and frontispiece; vol. 2, plate 26 ↑

Lechner, M., Squarr, C., in LCI 8, p.344-348, s.v. Siebenschläfer (sieben Kinder) von Ephesus. ↑

68 Paint.Man, p.59, s.v. The seven holy children of Ephesus, sleeping in a cave. ↑

See Chapter XII, Sveti Nikita ↑

Grozdanov, Cvetan, Sveti Sophia, Zagreb, 1988, p.43 ↑

Chatzinikolaou, A. in RbK II, 1046, s.v. Petrus von Alexandrien; Kaster, K.G. in LCI 8, 175-176, s.v. Petrus I von Alexandrien. ↑

2 Samuel 11 and 12 ↑

Psalm 51-a Psalm of David, when Nathan the prophet came unto him, after he had gone in to Bathsheba; Wessel, K., in RbK I, 1145-1161, s.v. David; Kunoth-Leifels, E., in LCI 1, 253—257, s.v. Bathsheba; Wyss, R.L., in LCI 1, 477-490, s.v. David; Kunze, K., in LCI 6, 35-36, s.v. David; ↑

Paris Gregory, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, gr.510,fol.143v., Constantinople, 880-886, a reproduction after Omont, fac-simile des miniatures, p. XXXIII, in DOP 41, 1987, p.429; Utrecht Psalter, 1996, p.70 and fig. 54 ↑

Genesis 37-50 ↑

In the narthex of St. Mark at Venici one can find an extensive mosaic about the same subject, which is dated to the thirteenth century; Loose, Helmuth Nils, Die Geschichte vpn Josef und seine Brüdern, die Goldmosaieken im Markusdom von Venedig, Freiburg, Basel, Wien, 1987 ↑

One of the eldest examples of the scene can be found in Ferrua, p. 78, pict. 51 ↑

See Chapter VII, Sveti Nikola at Varoš ↑

Grozdanov, Cvetan, Sveta Sophija, Ohrid, Zagreb, 1988, p. 45 ↑