Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

In the south-western part of Macedonia the landscape is dominated by two large lakes, Lake Ohrid and Prespa Lake, which are separated from each other by the Galičica Mountain range. Prespa Lake is in fact shared by three countries. The northern part is Macedonian, about one-third of the southern part is Greek, and a small part in the south-west is Albanian. Looking down from the Galičica range to the surface of the lake gives an impression of serenity, as if nothing has ever happened here.

A few hundred metres from the north-east shore of Prespa Lake, lies the archaic village of Kurbinovo. One or two kilometres outside the village, on a gentle slope at the foot of the Pelister Mountain range, stands a modest church dedicated to Sveti Djordje. One wonders why this church, which was not the katholikon of a monastery, is in such is a remote place. However, archaeological excavations in the vicinity of the church reveal that, up to the end of the eighteenth century, the village of Kurbinovo was located in the immediate neighbourhood of the church. The modern village now lies much closer to the lake.

The church stands on a man-made terrace surrounded and supported by hewn stones. From the outside it appears to be a simple building with a tiled saddle roof without any cupola (pictures 1-4).

Picture 1: Church from the southern side

Picture 2: Church from the western side with open portico

Picture 3: Church from the western side, entrance

Picture 4: Church from the eastern side with apse

It is built of hewn ashlars and bricks, which are covered with plaster. The first impression is that of a farmer’s house or shed, rather than of a church. It is a single-aisled timber-roofed church with an apse, having an inside length, including the apse, of 8.85 meters and a width of 5.30 meters. The walls are three quarters of a metre thick. On both sides of the apse there are small niches in the wall which have the function of prothesis and diaconicon, respectively. At the west end the saddle roof is somewhat lower and is continued to form an open covered portico. The wooden roof is a replacement of the original and was built after restoration work in the nineteenth century. During this work two windows were made in the south wall. Within this unpromising exterior it is surprising to see that the interior is partly covered with wall paintings of high quality, a large number of which have been preserved.

From Grozdanov, Cvetan and Hadermann-Misguich, Lydie, Kurbinovo, p. 41

It never had a cupola.[1] The church was more or less forgotten for a long time. The few historians, who visited the church before the 1930s, were of the opinion that its wall paintings dated from the sixteenth or seventeenth century. It was in 1940 that an investigator named R. Ljubinkovic drew attention to the church and concluded on the basis of comparable and dated frescoes in other churches, that this church dates from the twelfth century.[2] Conservation works carried out in 1959 brought to light an inscription in Greek letters on the right side of the altar. From this it could be deduced that the painting of the frescoes started in 1191. It is not known who commissioned the building of the church and its decorations.

In the years before this inscription was found a number of scholars and historians had attempted to date the wall paintings of this church on the basis of their style. The majority were of the opinion that the paintings were from the late twelfth or the beginning of the thirteenth century. Some scholars also compared the wall paintings of Sveti Panteleimon at Nerezi with those of this church. Although there are only thirty years between the paintings of the two churches and both belong to the Comnenian style of painting, the differences are nevertheless significant. As we have seen, the style of the Nerezi paintings was influenced by the court of Constantinople, through its founder Prince Alexios Angelos. Can the same be said of the paintings here? If we compare the angel of the Annunciation in this church (picture 5) with the same angel on an icon, now in the Monastery of Saint Catherine in the Sinai of about 1175[3], which is acknowledged as a masterpiece of late Comnenian art, the similarities are evident (picture 6).

Picture 5: Angel of the Annunciation

Picture 6: Annunciation to Maria, icon from the St. Catherine Monastery at Sinai, pict. 29, p. 160

The angel on the icon has the same elongated, slender figure and its drapery shows almost the same rippling and fluttering with meandering folds. The clothing of the figures has taken a life of its own. A corresponding angel can be found in a small church at Kastoria, in the Hagioi Anargyroi (picture 7).[4]

Picture 7: Angel, wall painting in Hagioi Anargyroi at Kastoria

A vague beginning of this style can be discerned in Nerezi, e.g. in the way the clothing of Johannes has been depicted in the scene of the Lamentation of Christ. It is generally believed that the icon in the Monastery of Saint Catherine was painted by a Constantinopolitan artist. This is suggested by the technical handling of the gold and by the intricately painted design on the reverse, also found on other icons, all works that must have been painted at Sinai. Consequently, it may be assumed that the main painter of the Kurbinovo church had knowledge of the way of painting that was applied at that time. The same style can be seen in some parts of a tetraptych with the Dodecaorton, also in the Sinai Monastery[5], as well as in a number of manuscripts. It may therefore be assumed that this manneristic style, which occurred in different places within a restricted period of time, originates from one single centre, and that is Constantinople.

It is generally accepted that the wall paintings in the Kurbinovo church were not painted by one artist.[6] Those on the east wall have been painted in a somewhat more subtle style than the other frescoes. The latter have more dark colours and ochres and the faces are more lined, which is generally indicative of a more provincial style. Whereas the Nerezi frescoes are predominantly graceful and express humanity and sometimes emotions, the Kurbinovo wall paintings are striking by the use of vivid expressions and movement. They have a particular articulation of the human body, with an expressive linearity in the hair, in movement and the meandering in the clothing of the figures exposed. The characterised faces are solid with strong lips and noses and clearly indicated cheekbones.

Originally there were three rows of paintings on the north and south walls. Those in the top row have been only partly preserved. On the south wall there was probably a row of about sixteen standing prophets, each holding in his left hand an unrolled scroll with a text. Nine of these texts are partially readable. The presence of prophets in the top row is a clear indication that the church never had a cupola, for that was the place where prophets would usually have been depicted between the windows of the drum. The second row consists of a cycle of Christological scenes belonging to the Dodecaorton, the twelve feasts of the Orthodox Church. This starts at the east side of the south wall and continues – via the west wall – on to the north wall. The bottom row contained a number of saints, most of which have disappeared. We may assume that a church dedicated to a special saint, in this case Sveti Djordje, had a number of wall paintings relating to the saint’s life and sufferings. Only two such paintings remain on the north wall.

The north wall has been arranged in almost the same way as the south wall, but unfortunately in the bottom row the majority of the paintings has disappeared. On the top row, the feet of fifteen prophets are visible and only five hold an unrolled scroll. The lower paintings of the north wall have almost all disappeared.

The west wall consists of four rows of paintings which partly form a continuation of the Dodecaorton cycle, including the Koimesis. There is no reasonable explanation why the painters put the scenes of the Entry into Jerusalem and the Metamorphosis left and right of the Koimesis. The scene at the top is heavily damaged and it is not clear what it originally showed. The lower row shows Christ enthroned and surrounded by angels. The paintings of the apse and on the west wall are best preserved.

The border that frames the triumphal arch from the half-cupola of the apse contains a text, which is rather unusual. The translation of the Greek text is as follows: “They came to your child, like slaves, the heavenly hosts, rightly perplexed by your child-birth, without seed, O You who will always be a Virgin. For you are pure, both before the conception as after the birth.”

On the half cupola of the apse the Virgin Enthroned has been depicted with a Christ child playing in her lap. Her left arm is around his waist while her right hand holds one of the legs of the child (picture 8).

Picture 8: Throning Virgin with two angels

She is dressed in a red maphorion over a blue chiton. The Virgin does not look at the child, but to the contemplator in the church. The child looks towards his mother, his right hand makes a gesture of blessing and in his left hand he holds a scroll. His gold-shining himation flutters behind him. The throne has no back, but is beautifully adorned with precious stones and marquetry of ivory and nacre. The Virgin sits on an embroidered red cushion, with her feet resting on a suppedium decorated in the same manner as the throne. The background is blue and the lower part is green, representing heaven and earth. The composition of the representation of Christ is considered as a Maria Hodegetria, she who shows the way, but its form is somewhat unusual since she does not explicitly point to the child. Both are flanked by the two archangels Michael and Gabriel with large beautifully coloured wings, who hold their open hands towards them (pictures 9 and 10).

Picture 9: Angels Michael and Gabriel

Picture 10: Angels Michael and Gabriel

The scene as such can be compared to that of the empress at the court in Constantinople, flanked by court dignitaries. The clothing of both angels has been depicted in the same manneristic way with a lot of flutters and curves and fluttering himations. They both wear adorned red shoes, like the angel in Kastoria (picture 7)

In larger churches the Communion of the Apostles is usually depicted below the scene of the Virgin Enthroned in the half dome of the apse, and one row lower is the place for officiating or frontally standing bishops. In this church, however, we see below the Virgin only the co-officiating bishops at an episcopal celebration. As usual they are clad in the polystavrion phelonion, a chasuble decorated with crosses and around their shoulders they wear the omophorion, a pallium decorated with large crosses. Each of them holds a scroll with a text from one of their sermons or books. It is not certain who they are exactly, but taking into consideration their physiognomic features it may be assumed that they are, from the centre to the left side: Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory Thaumaturgos, Gregory of Nazianz and Basil the Great of Caesarea (picture 11).

Picture 11: Four archbishops

The translated Greek text of the scroll of Gregory of Nyssa reads: “Lord our God, who dwells in the high heavens, who considers the humble.”

Basil’s scroll reads: “None of them who are bound by fleshly lusts is worthy.”

From the centre to the right we see: Ioannes Chrysostomos, Athanasios of Alexandria, Achilleus of Larissa and Nicholaos of Myra (picture 12).

Picture 12: Four archbishops

Details about lives of most of these bishops have been given in Chapter VIII. Achilleus of Larissa came from Capadocia. He became Archbishop at Larissa in Thessaly and attended the Council of Nicea in 325. He was venerated as a worker of miracles. His relics were transferred from Larissa to Prespa in 986 on the orders of the Bulgarian Czar Samuil. There Achilleus became the patron saint of Samuil’s cathedral church on the island which bears the saint’s name. This saint has not been depicted as frequently as others, but his reputation in the Prespa area explains his presence in this church[7].

The translation of the Greek words on the various scrolls reads as follows: Ioannis Chrysostomos: “Lord, O our Lord, who has given us the heavenly bread, the food for the whole world.”; Anthanasius: “Lord our God, whose power is incomparable and the glory”;

Achilleus: “Lord our God, save your people and bless your inheritance”; and Nicholaos: “You, who have given us common and united prayers”.

The two rows of bishops stand in three-quarter pose in the direction of a so-called Melismos (picture 13) to celebrate the Eucharist.[8]

Picture 13: Melismos

The depiction of the Christ-child lying in a paten instead of bread began at the fringes of the Byzantine Empire. It is very likely that, in order to combat the heretical movement of Bogomilism, the Orthodox Church deliberately chose to depict explicitly the transubstantiation, in which the bread and wine through the intervention of the Holy Spirit become the body and blood of Christ. The first dated example is in the church of Kurbinovo.[9]

About the same time another Melismos was painted in the Hagioi Anargyroi Church at Kastoria. The biblical basis for the Melismos are the words of Christ: “And as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed it, and brake it, and gave it to the disciples, and said, Take, eat; this is my body.”[10] In this church there is one of the first representations of the body of Christ lying on the altar table.[11] In later depictions the Christ-child is shown in the paten itself. The painted altar table stands just below the window of the apse and is covered by the large aer and by an oblong purple cover, the kalymna. Just behind the kalymna there is an asteriskos, which consists of two bent braces to prevent the offering from being touched by the kalymna. At the head of the Christ figure the chalice has been depicted. Usually the body of Christ at the Melismos is surrounded by officiating church fathers of the Great Entrance[12] and sometimes two angels. The number of church fathers differs as well as the figures; there is no rule as to who may be present.

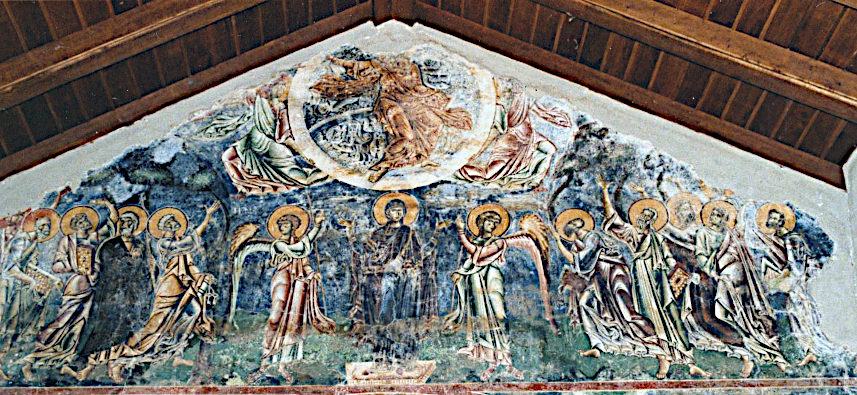

At the top of the triumphal arch around the half dome of the apse is the Analepsis, or The Ascension of Christ (picture 14) which is referred to in the Acts: “And when he had spoken these things, while they beheld, he was taken up; and a cloud received him out of their sight. And while they looked steadfastly toward heaven as he went up, behold, two men stood by them in white apparel, which also said: You men of Galilee, why stand you gazing up into heaven? This same Jesus, who is taken up from you into heaven, shall also come in like manner as you have seen him go into heaven.”[13]

Picture 14: Triumphal arch with Ascension of Christ

After the period of Iconoclasm in older churches the Ascension scene is sometimes depicted in earlier churches in the cupola, as in the Church of Ayia Sophia in Thessalonica, but in later churches it is often placed on the barrel vault of the naos or the bema before the apse. The placing of the Ascension scene on the triumphal arch is remarkable and rare and as far as can be determined, it is the first time that this occurs within the Byzantine Empire and its fringe areas.

The wall painting of the Ascension is slightly damaged at the sides and top, the damage being caused when the new roof was built. Two large angels with fluttering clothes hold the mandorla in their hands and take it to heaven (picture 15).

Picture 15: Triumphal arch with Ascension of Christ, detail Ascension

The mandorla has been shown as a white circular shape that surrounds the figure of Christ. He sits on an arch of heaven and his feet rest on a rainbow.[14] His dress is shiny gold and his himation flutters behind him. He holds a richly decorated book in his left hand and makes a gesture of blessing with his other hand. Unfortunately the head of Christ has been lost. Within the mandorla strange creatures surround Christ: a number of fishes and snakelike animals are there and on the left there is an animal in the shape of a lion: all are surrounded by strange creatures and waves. It was perhaps inspired by the words in Revelation 5:13 “And every creature which is in heaven, and on earth, and under the earth, and such as are in the sea, and all that are in them, heard I saying: Blessing, and honour, and glory, and power, be unto him that sits upon the throne, and unto the Lamb for ever and ever.” It is a unique rendering, no other example of which, as far as I know, exists and for which no other reasonable explanation can be given. There is no relation with the zoomorphic depiction of the tetramorphs mentioned in the vision of Ezechiel, or with the beasts in the Revelation.[15] In this connection, reference has been made to the third prophet on the south wall of the church holding a scroll with the words of Zechariah 14:1 and 4 “Behold, the day of the Lord cometh” and “And his feet shall stand in that day upon the mount of Olives….”[16] These words have a relation to the return of Christ and the Last Judgment, but in my opinion do not refer to his Ascension. A reference can even be made to the words in Psalm 104:3 saying: “Who layeth the beams of his chambers in the waters: who maketh the clouds his chariot: who walketh upon the wings of the wind:” During that period Bogomilism had not yet completely disappeared from the country or its believers excommunicated, but the suggestion that the mysterious animals were painted under the influence of Bogomilism lacks proof.

The heavenly atmosphere of the Ascension has been depicted in blue, while the earth where the disciples and Maria stand gazing upwards is green. Below the ascending Maria the Virgin stands on a footstool in orante attitude. She is dressed in a purple maphorion over a blue dress. She is flanked on both sides by an angel, each of which addresses the disciples behind them. The angels’ hands point to the sky above and they each hold a staff with a lily at the end as a sign of their dignity. Their wings are outstretched.[17] Only Maria and the angels wear shoes, those of the angels being stitched with pearls. The angels are androgynous of nature. On both sides of the scene, eleven disciples with gesticulating arms look around in astonishment. To the left Peter stands with five other disciples: he holds two keys in his hands (picture 16).

Picture 16: Disciples at the Ascension

This refers to the words of Christ spoken to Peter in Matthew: “And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven”.[18] The figure painted just behind Peter is most probably Andreas, who is recognisable by his dishevelled hair. Although no names have been mentioned on the other side we can recognise by his physiognomy Paul, who is followed by four others (picture 17).

Picture 17: Disciples at the Ascension

The presence of Paul is remarkable, because he is only mentioned at a later date in The Acts. But he can be seen in many older examples in various churches on different occasions. Early on in the history of Christianity he was considered to be one of the most important disciples. In the scene, four of them are holding a book and we may assume that they represent the four evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke and Johannes, although Luke was not one of the disciples. The dark haired man on the right is probably Mark, and the young looking man on the left, second behind Peter, is assumed to be Johannes. They are standing in a paradise-like setting with palm trees. Eleven disciples correspond to what is told in The Acts. After the Ascension the eleven disciples returned to Jerusalem and appointed a man named Matthias as the twelfth to replace Judas Iscariot. However, Paul rather than Matthias is usually shown in the depictions of the twelve apostles.

Below the Ascension of Christ on either side of the arms of the Triumphal arch there is a painting of the Annunciation of the Virgin[19], the first of the feasts of the Dodecaorton. The painting is one of the most beautiful in this church and can usually be seen in all handbooks dealing with Byzantine art. On the north side of this work a long slender Archangel Gabriel with outspread multicoloured wings raises his right hand in a gesture of speaking towards the Virgin[20] (picture 5). In his left hand he holds a long staff, which is the attribute of a divine messenger. His face is young and shows he is aware of his important duty to bring a message to a mortal human being. On his long light brown hair he wears a tania. Also here the painter has depicted his clothing, the himation and the tunic with many manneristic folds which move in the air and around his legs. It seems as though he is floating in the blue air and his feet, with jewelled shoes, barely touch the earth which has been depicted in a green colour.

Opposite him the Virgin Maria sits before her house on a richly decorated throne without a back or elbow-rests. Her feet rest on a suppedium (picture18).

Picture 18: Maria of the Annunciation

She is portrayed as an empress at the court of Constantinople might have appeared. On the throne lies an embroidered cushion that is covered with a cloth that is beautified with lilies. She is busy spinning the purple yarn. The basis of her spinning lies in an old story: “Now there was a council of the priests saying ‘Let us make a veil for the temple of the Lord.’ And the priest said ‘Call to me pure virgins of the tribe of David.’ And the officers departed and searched and found seven virgins . . . and the priests said ‘Cast lots to see who shall weave the gold, the amiantus, the linen, the silk, the hyacinth-blue, the scarlet and the purple.’ The pure purple and scarlet fell by lot to Maria. And she took them and went home.”[21] The Virgin looks somewhat surprised in the direction of the angel and her right hand makes a gesture as if she is responding to the salutation of Gabriel. Similarly to Gabriel she has been depicted as a slender young woman with relatively long legs. Her face is clear and calm with a sharp nose and small lips. Her head, with wide open eyes, looks at the angel. In the background her house has been illustrated as having a small roof garden surrounded by a fence. On this roof three trees are growing, one in a large vase. They fit naturally in the background. On the icon in Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai, referred to earlier, [22] (picture 6) there are some trees in the background on the roof of the house.

They serve as a metaphor which Byzantine artists used to express the meaning behind the Annunciation.[23] As a tree takes roots and can withstand storms, so the Lord vested the roots of the religion through the Virgin. “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots: and the spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and of the fear of the Lord;”[24] “But out of a branch of her roots shall one stand up in his estate...”[25] Below this double scene are two niches which most probably served as prothesis and diaconicon.[26] Each of the niches has inside it a portrait of a saint. In the prothesis below the Archangel Gabriel, a deacon has been painted whose name has not survived. It is possible that it is Stephen, the first deacon martyr (picture 19), who is usually shown on the left side of the triumphal arch.[27]

Picture 19: Deacon Stephen

He was the first of seven men at Jerusalem to be ordained deacon.[28] He was accused of speaking blasphemous words and was brought before the Sanhedrin. He defended himself with a lengthy speech which made the accusers the accused. Although no sentence was pronounced he was stoned to death and became the first Christian martyr.[29] He is dressed in the white diaconal sticharion and from his left shoulder hangs a small orarion, on which some small embroideries including a cross can be seen. In his left hand he holds a cross. He is beardless. At the other side in the diaconicon below the Virgin another deacon has been painted, dressed in the same way as Stephen. He also holds a cross in his left hand and he also has been depicted with a young beardless face. It is generally accepted that he is Euplus of Catania on Sicily (picture 20), whose fame was widely spread, especially in the Near East.[30]

Picture 20: Deacon Euplus of Catania

It is likely that he was martyred by the sword, after being found with a copy of the gospels in his possession in defiance of one of the edicts of Emperor Diocletian.

It is generally accepted that the paintings of the apse and the triumphal arch were painted by the most skilful painter. The other walls have apparently been painted by one or more other artists. The style differs, the meandering and lightness of line in the draperies are much more restricted. The way some of the faces have been painted, in particular the faces of women, is indicative that it was done by a less skilled painter. Very heavy lines and sharp noses give the impression of old women, although this may be an attempt to express their suffering, as with the women at the empty grave.

Where the south wall joins the east wall there is the scene of the Meeting of Maria and Elisabeth, called the Visitation or aspasmos (picture 21).[31]

Picture 21: Visitation

Earlier representations of the Visitation are rare, with the exception of a sixth century mosaic in the apse of the Euphrasia Basilica at Poreč in Croatia. The scene in this church has been painted as if it was the first in a cycle of feasts of the church. The Visitation was however, never a recognised feast. Nor was it the object of any special liturgical event. The elder Elisabeth and the younger Maria embrace each other (picture 22).

Picture 22: Visitation, detail

Both women are pregnant. When Maria entered the house of Elisabeth and Zacharias, and Elisabeth heard the salutation of Maria, the baby leaped in her womb. And she said to Maria: “…Blessed are thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb. And whence is this to me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me?”[32] In a theological sense the words mean that Elisabeth is the first to proclaim the divinity of the child that Maria bears. Her words “the mother of my Lord” refer to the Incarnation and are a proclamation of this mystery.[33] The women have been painted in a moving action suggesting that they ran to each other. Their long robes trail in the movement. It looks as though they are moving through the air without touching the ground. The painter has depicted them in a linear style and has clearly indicated the muscles and form of the legs. They meet “in a town in Judea” where Elisabeth was living, as has been indicated by the buildings in the background. On the right side of the same wall painting the women are sitting opposite each other with different gestures of their hands as if they are discussing the wonderful things that had happened to them. The Visitation is not painted frequently and then usually both women are standing. That the women are sitting is unusual, but that they are rendered twice in one wall painting is a rarity.

A niche-like painted ornament is seen on the south wall above the head of the large, standing figure of Christ Pantocrator, which is painted larger than life size. The niche has almost the same form as can be seen around the head of Panteleimon in the church of Nerezi, but there it was a round trefoil stucco arch with sculptured plaited ornaments. This niche creates the impression of atmospheric space. The wall painting is slightly damaged, but it is recognisable that Christ holds a jewel-studded Gospel book in his left hand, and with his other hand, which has relatively long fingers; he makes a gesture of blessing (picture 23).

Picture 23: Christ Pantocrator

The cross in his nimbus is adorned with jewels. His hair is parted in the middle and falls onto his shoulders. There is a small curl on his forehead. There is an expressive linearity in his hair and in his curled beard. His wide open eyes under raised eyebrows are not fixed on a particular point. The cheeks have been indicated by some ochre lines of paint. He is Christ Pantocrator, He who rules everything, who holds everything in His hand, the Almighty.[34]

Just opposite him on the north wall is a similar portrait of Djordje the saint after whom this church is named. Instead of the usual red line that borders a wall painting both paintings have been adorned with ornate painted frames. This serves to stress their importance.

Somewhat lower down on the right side of Christ some remnants of a wall painting of the Virgin (picture 24) together with John the Baptist can be seen.

Picture 24: Maria of the Deesis

They both stand facing in the direction of Christ and each of them holds an unrolled scroll. It is possible that the painter had intended this scene as a Deesis, which is a supplication to Christ to have mercy upon mankind when He judges the world. The painting of John reveals only the middle part of his body, the rest has disappeared. The Greek words on Maria’s scroll read: “What do you ask mother? The salvation of the mortals? They have made me angry. Have pity on them, my son.” These remarkable words form a dialogue between Christ and his mother. The words of Johannes translate: “Behold the Lamb of God, which takes away the sin of the world.”[35]

The next scene in the third row in the christological cycle is the Birth of Christ, the Gennesis (picture 25).[36]

Picture 25: Birth of Christ

It was originally a relatively large scene, but the left side disappeared when a window was made, during restoration work in the nineteenth century. Judging by the manner of painting we may assume that the master painter, who was responsible for the scenes in the apse and the east wall, also painted large parts of this scene and was at least responsible for the clothing of the angels which has been depicted full of meanders and fluttering. The painters of this wall painting have included some interesting features. Usually the child lies inside the cave in the manger and his mother is in front of him. But the painters have chosen to depict Maria in front of the cave. She lies in a reclining pose on a mattress and the swaddled child lies in front of her. Maria’s head is turned towards the child as if she is looking at him, but in fact her eyes are directed to the onlooker in the church. Her head rests on her right hand while her left arm and hand lie alongside her body. The child lies in the manger, which has an altar-like structure. The cave has been depicted as being inside a mountain, and consisting of layers of diamond shaped stones. On the left behind the mother and child the ears of a donkey and the horns of the ox are still visible. They are a reference to the words of Isaiah: “The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib: but Israel doth not know, my people doth not consider.”[37] In the earliest birth scenes from the first centuries, some from sarcophagus covers, both animals were usually present.[38] Five angels move around this scene with outspread wings and gesticulating arms. The two in the centre raise their hands to heaven, indicated as a small round form from whence a beam of light shines down; the angel on the right announces the birth of Christ to the shepherds. Two shepherds are shown: an older man dressed in a white melote carrying two crooks on his shoulders and a young boy in a strange hat sitting crossed-legged on a rock playing an oaten-pipe. A shepherd with a flute has been included in this kind of scene since the beginning of the Middle Ages. One of the earliest examples can be seen in the katholikon of the Hosios Lukas in Greece. Between the shepherds and the mountain a round form has been painted with sheep inside. This is understood to be a fence made of branches, which until the present day shepherds use to make a safe place for the sheep to protect them from wild animals during the night. A dog watches attentively. Below this part of the scene – which is seriously damaged – two midwives are busy bathing the Child. They became known as Salome and Zelomi.[39] Remarkable, especially in Byzantine art, is the fact that it looks as though the midwife at the right side has been illustrated with a bare shoulder. On the far left, where part of the painting has been removed to insert the window, two angels look back at the persons who are following them. The last angel points down to the Child. Most probably they are showing the way to the three wise men who had seen and were following a star in the east. Just above the head of the last angel a hand holds a jewel-studded box with the form of a crown on it, a present to the new-born King of the Jews. The background of the scene is deep blue.

To the right of this scene there are only some remnants of a wall painting of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, the Hypapante.[40] A large part of the wall has been destroyed in order to insert a window. In the centre of the scene, two richly carved closed doors can be seen before a ciborium under which stands an altar table with two glasses; to the left of this stands the only intact figure, in this case Simeon with the Christ-child in his arms. Only the feet of the child can be distinguished. Behind him there was another figure of which only fragments of the nimbus and a small part of an unrolled scroll have been preserved. We may assume that this figure was that of the Prophetess Anna. At the right side just below the window two pairs of feet, very likely those of the Virgin and Joseph, can be distinguished. Although the scene has been seriously damaged it is clear that the painter who depicted the face of Simeon was a skilled craftsman who has succeeded in giving it a serious expression. He has heavy eyebrows above attentive eyes, a sharp nose and his cheeks are indicated by a single line. His linear hair and beard are somewhat dishevelled. On the left side in the background there is a cupola which may form part of the buildings of the temple.

Next to it on the south wall there is a depiction of one of the other feasts of the Dodecaorton, the Baptism of Christ, (picture 26).[41]

Picture 26: Baptism of Christ

The scene was probably painted by one of the painters who worked on the scene of the Gennesis. The main colours are ochre on a blue background. The undressed Christ stands in the water of the River Jordan up to his shoulders. The river is bordered by a mountainous landscape, which has almost the same form as the mountain and cave in the scene of the Birth of Christ. Christ has been depicted as an adult with a small beard. An ascetic John the Baptist stands in a bending position on the left bank of the river. He is dressed in a chiton of dark brown camel’s hair with a belt around his waist. With his left hand John baptises Christ and with his right hand he makes a gesture towards him.[42] Christ holds his left hand to his chest and his right hand makes a gesture of blessing towards a figure beneath him, who represents the personification of the ancient river god. The river god holds a stone bottle in his hand from which water runs to feed the river[43], and he looks up at Christ with raised hand as if to receive the blessing for his water. Although from the beginning of Christianity pagan mythology was resolutely rejected, nevertheless some elements offered the possibility for Christianisation by incorporation into Christian themes. On the other hand it is sometimes said that Byzantine art is in some way a continuation of the former Greek art. The inclusion of the river god is in fact an example of such a continuation. A precious cross has been set up on a marble column in the water behind the personification of the river to mark the place of the baptism of Christ. The cross may be a reference to Paul’s words to the Romans: “Know you not that so many of us as were baptised into Jesus Christ were baptised in his death?”[44] On the other side of the river two angels with covered hands are standing ready with new clothes for Christ. They are both witnesses and servants of Christ. Above the head of Christ there is a small segment of a circle which indicates heaven. The pigeon usually depicted as the symbol of the Theofany is missing here.

The last Christological scene on the south wall is the Raising of Lazarus (picture 27).

Picture 27: Raising of Lazarus

It is sometimes considered to belong to the cycle of the Passion of Christ: the Raising of Lazarus from the dead is considered as prefiguration for Christ’s resurrection from the dead. For the earliest Christians it symbolised the hope of an eternal life as is witnessed by about forty paintings which have survived in catacombs.[45] The story of the Raising of Lazarus is only mentioned by the Evangelist Johannes.[46] The wall painting shows a mountainous landscape with two mountains. On the left side Christ, followed by a number of disciples, has outstretched his right hand in a blessing gesture towards Lazarus whom he summons to come forth from the grave. In his left hand he holds a scroll. Christ is dressed in a dark chiton with a himation that falls down in folds from his right shoulder and from his left arm. On the right Lazarus stands upright, completely bound in grave-clothes, inside a mountain cave in the form of an aedicula. His head is partly covered with a soudarion, but his face and forehead are uncovered. To the left of the aedicula, a man in a dark chiton holds a cloth to his face, a reference to the words of Martha, the sister of Lazarus: “Lord, by this time he stinketh”, for Lazarus had been dead for four days. The man is busy loosening the sindonia from Lazarus’s body. At the right side beneath the feet of Lazarus, only partly visible because of damage to the wall painting, another man, bent under its weight, struggles to remove the stone from the place where the dead body was laid. In spite of more damage to the wall painting the two sisters of Lazarus, Martha and Mary, are clearly visible at the feet of Christ, as they pay homage to the Lord. It was Mary who anointed the Lord with ointment and wiped his feet with her hair.[47] Martha looks back towards her risen brother. The evangelist reveals that many Jews who came to the house of Mary and Martha (some of them had seen the things He did) believed in Him, but others went away to tell the pharisees what had happened. On the far right a number of Jews has been depicted. One of them raises his hands in astonishment. Between Christ and Lazarus some low vegetation can be seen. This painting has been compared with a wall painting from about 1106 in the Church Panayia Asinou on Cyprus (Panagia Phorbiotissa or Panagia tis Asinou), which in a more refined way shows the same scene. Almost all the elements of that painting are to be found in the Kurbinovo painting, although in a more provincial style.[48]

At the left side of the south wall the cycle of the Dodecaorton continues with Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, or Baiophoros (picture 27a).[49]

Picture 27a: Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem

It is a relatively small wall painting in which all the well-known elements have been included. For the early Christians emphasis was laid on the symbolic meaning of the entrance of Christ into the Heavenly City after gaining victory over death. In a mountainous landscape, Christ, who sits astride the foal of an ass, rides to the right in the direction of Jerusalem. He is followed by his disciples, two of which have been indicated. Christ looks more in the direction of his disciples than the city. Christ is dressed in a blue himation over a brown chiton. He holds a scroll in his left hand. Two small figures are busy spreading their garments in the way; they look up at Christ. In a tree in the background two people are busy cutting off branches. One is sitting in the top of a palm-tree.[50] Although the Evangelists speak of a great multitude crying: “Hosannah to the Son of David. Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord; Hosannah in the highest”, only two serious looking men and a woman are pictured welcoming him at the gate of Jerusalem. The man in front has raised his arm to greet him. He holds a child by the hand, who is very naturally, scratching his foot. The presence of a woman can be explained by the words of some evangelists: ‘Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Sion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: behold, thy King cometh unto thy: he is just, and having salvation; lowry, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass.”[51] The background of the scene is a huge mountain. Christ has been depicted in the foreground against a blue sky.

In the centre of the southern wall is a rendering of the Koimesis, which will be dealt with later.

At the right side of the Koimesis there is a painting of the Metamorphosis or Transfiguration (picture 28), the story of which has been told by three of the evangelists.[52]

Picture 28: Metamorphosis

Christ took with him into the mountains Peter, Johannes and Jacobus and he went up to pray. And when He was praying his countenance altered and his face did shine like the sun. His raiment became white as snow and was glistening. It seemed as though He was hovering in the air. In the painting He is dressed in a white shining chiton and himation. He makes gesture of blessing with His left hand and holds a scroll in His right hand. Christ is surrounded by a circular shaped mandorla, which resembles a wide white wheel with flames bursting from the inside. Christ is in a heavenly mandorla, from which beams of light go into all directions.[53] The transfiguration is a glorious Theophany of Christ, and, in its multidimensional theological meaning, bears witness to the Incarnation of the World and the revelation of the divinity of Christ, as well as portending his resurrection and second coming.[54] Christ stands on the top of a mountain. On the right side a beardless Moses can be seen, standing on the top of another mountain. He holds the tablets of the law in his right hand. Elias stands on the other side. His hands are raised in supplication towards Christ. Two of the shafts of light are directed to them. On earth the three disciples, from left to right Jacobus, Johannes and Peter, lie on the ground. Each of them looks up to the miracle that is happening before their eyes. Their hands are raised in astonishment or maybe anguish. Peter points to Christ above him as if he is saying: “… Master, it is good for us to be here: and let us make three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elias….”[55]

The figures are elongated and although some of the paint has vanished, the faces, especially of Elias, show character. His face resembles that of Simeon at the Hypapante and is most probably painted by the same artist. A comparison can be made with an analogous painting in a nearby church, painted some years earlier, the Ayios Nikolaos Kasnitzi at Kastoria (picture 29).

Picture 29: Metamorphosis, from Ayios Nikolaos Kasnitzi at Kastoria

It has an almost similar iconological scheme, although the three disciples lie in a reverse sequence and Moses and Elias have changed places.[56] Between the bare rocks of the mountains some plants have been painted.

The cycle of the Dodecaorton continues on the north wall with the Crucifixion (picture 30).[57]

Picture 30: Crucifixion

The paintings on the north-west side of the church are somewhat less colourful, partly because of calcimining of the wall. In places the paint has disappeared, although the blue background remains. The wall painting shows a lifeless Christ hanging on the cross, His hands nailed to the heavy cross-beam or patibulum, and His arms slightly bent. His body, contorted and bent, is naked except for a sublicagulium, or loincloth. His head inclines on His right shoulder. His feet rest on the suppedaneum.[58] Christ has been depicted as being already deceased. From His feet, blood drips onto a skull beneath the cross, which lies in a hole in a mountain-like place.[59] Legend tells that here on this place the skull of Adam was buried. The Synaxarion for Good Friday states: “It is said that the skull of Adam is lying there, where Christ, the Head of all, was crucified. Adam will be baptised anew by the blood of Christ that flows from His feet. Golgotha is the name of that place, because the skull of Adam was carried away from earth by the Flood and was floating around alone as a visible, miraculous sign. Solomon and his whole army buried it under a pile of stones. This is the reason why, from that time on the place was also called Lithostrotos. It is said by the authorities among saints that they knew from legends, that Adam was buried by an angel as well. Where once the body was, in that place came the eagle Christ, the eternal King, the new Adam, who cured, by the wood of the cross, the old Adam who fell by the wood”.[60]

At the right side beside the cross, Johannes is mourning, his face suffused with sorrow. His head rests on his right hand. At the other side the Virgin, accompanied by two unidentified women, reaches out her hands towards the body of her son.[61] At the top of the cross above the head of Christ a piece of wood containing the accusation can be seen.[62] Two wailing angels float in the air. On the far right a soldier has been depicted holding a large spear upright in his left hand, with his other hand he points at Christ. He has no nimbus. His head looks at Christ while his body is moving in the opposite direction. Most probably it is the centurion who said: “Truly this man was the Son of God”.

It is striking that the painters have depicted the Mountain of Golgotha here in the same way as they did the mountain in the scenes of the Birth of Christ and of the Baptism.

Next to this scene the Deposition from the Cross has been painted (picture 31).[63]

Picture 31: Deposition from the cross

Joseph of Arimathea, standing on a ladder, holds the body of Christ in his arms to take it down from the cross. Joseph’s body is bent under the weight of the dead body of Christ. Nicodemus, also standing on a ladder, is taking away a nail from the left hand of Christ. The Virgin stands on the left and lovingly holds the right hand of Christ against her face. Johannes stands between the two busy men; his body slightly slumped in his grief over his Lord’s death. Behind the Virgin a number of women have been shown without indication of who they are. The same two angels still float in the air. The lower part of the scene has not been preserved, but we may assume that the long band with decorations on it is an indication of the walls of Jerusalem. Some parts of the painting have been made by less skilful painters, for example, the figure of Johannes and the strange arm of Nicodemus.

To the right of this scene is one of the original windows and then a continuation of the previous scene, the Threnos, the Lamentation of Christ (picture 32).

Picture 32: Lamentation

It is reminiscent of the same scene in the church at Nerezi. Maria, in a partially squatted position behind the body of Christ, holds her son in her arms. There is deep grief on the face of the Virgin, which expresses restrained sorrow. Somewhat behind her Johannes deeply bends towards the body of Christ and holds the left hand of Christ to his face and with his left hand he holds the side of Christ. At the far end Joseph of Arimathea holds the feet. Both men look at Christ with profoundly melancholic expressions. Christ is dressed only in the same sublicagulium as at the Crucifixion and the Deposition from the Cross. This is remarkable, because the four Evangelists mention that his body was wrapped in linen. Just above the head of Christ and his mother an open sepulchre has been depicted. The three appear to be carrying the body of Christ to the open grave.[64] It was apparently the intention of the painter(s) to depict both the Threnos and a sepulchre. The surroundings are mountainous. “Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden; and in the garden a new sepulchre, wherein was never a man yet laid. There laid they Jesus therefore because of the Jews’ preparation day; for the sepulchre was nigh at hand”.[65] In the background two women, who were witnesses are sitting on the mountainside. One is in an attitude of deep grief with one hand under her chin, almost covered by her maphorion. The other woman has raised her hands to express her sorrow. They may be Mary of Magdala and the other Mary.[66] Above their heads angels float in the air.

Next to this scene a relatively small wall painting depicts the myrrophores, bearers of spices, at the empty sepulchre (picture 33).[67]

Picture 33: Angel at empty grave and myrrophores

The actual Resurrection of Christ, the corporeal uprising from the grave, has remained a mystery and has not been described by the Evangelists. What is usually depicted are women at the empty sepulchre, one or two angels and sometimes sleeping soldiers. “In the end of the Sabbath, as it began to dawn toward the first day of the week, came Mary Magdalene and the other Mary to see the sepulchre. And, behold, there was a great earthquake: for the angel of the Lord descended from heaven, and came and rolled back the stone from the door, and sat upon it”.[68] The scene shows the two women at the left side, depicted as long standing figures with grieving faces, holding in their hands the sweet spices to anoint the body of Christ. The countenance of the angel is like lightning and his raiment is as white as snow. His large wings are outstretched. With his right hand he points to the empty sepulchre in which lie the bindings – sindona and soudarion, indicated by letters. In his other hand he holds a staff ending in a lily, as a herald, the symbol of the divine origin of his words. The soldiers who were guarding the grave lie down as if dead men, still holding their shields and spears. This part of the wall painting is slightly damaged. Apparently two painters were working here; most probably the most skilled painted the angel, the other one the women.

To the right of this scene and opposite the figure of Christ on the south wall there is a large painting of Djordje (picture 34), the saint to whom this church is dedicated.[69]

Picture 34: Djordje

It is generally agreed that Djordje originates from Capadocia, where he became a soldier under Emperor Diocletian. As a Christian he was often tortured.[70] He is sometimes depicted, as in this church, clad in armour as a soldier, and sometimes as being tortured. The top of the painting is surrounded by a painted round trefoil arch with flower ornaments, which rests on painted columns each having a Corinthian capital. Djordje has been illustrated here with a pearl diadem on his curled hair, scale armour and a spear in his right hand. His military dress is richly adorned. Most probably there was a shield in his other hand, but that side of the wall painting has disappeared. He has been painted with a sharp nose, small mouth and heavy eyebrows. We may assume that in a church bearing the name of a saint there were more wall paintings relating to his life and significant events, but unfortunately these have not been preserved.

Next to Djordje on the right is one of the best preserved wall paintings in the church. It shows the Anastasis,[71] the Descent of Christ into Hades (picture 35) to relieve the souls of the dead who had died before Christ himself was crucified, and who were dwelling in the underworld.

Picture 35: Anastasis

The story is extensively told in the so-called Gospel of Nicodemus or Acts of Pilate.[72] It reveals that John the Baptist as the last of the prophets came into the midst of Hades where he taught those who were there that the Son of God would come to release them. Then a voice like thunder sounded that the gates should be lifted up. The gates of brass were broken into pieces and the bars of iron were crushed and all the dead who were bound were released from their chains. The scene is one of the twelve feasts of the Dodecaorton, but it is hardly known in western countries.[73]

The unmistakable triumphal meaning of the Anastasis scene, however, is well known. Iconographically, the Descent into Hell, as it was created in late antiquity, is a replica of allegorical representations of the victorious Roman emperor shown pulling towards him the kneeling or prostrate personifications of the conquered city. The liberator of the vanquished, who were thought to have been torn from the tyranny of their leaders by the Roman emperor, is compared to Christ as victor over the tyrannical prince of death; he liberated and took to himself all the unwilling inhabitants of his kingdom, starting with Adam and Eve.[74] In almost all churches containing an Anastasis scene, Christ has been depicted standing with both legs in the broken wings of the gates of hell. The gates usually lie crosswise over each other.

In this wall painting Christ is in a circular mandorla. He does not stand on the broken doors of hell, but ascends; his himation is fluttering behind him. With his right hand he pulls the aged, half kneeling Adam from a sarcophagus.[75] Christ triumphantly holds a large patriarchal cross in his other hand; the wreath of thorns has been added to the middle of the cross. Behind Adam stands Eve in an attitude of supplication with covered hands. Behind Eve the young man shown in simple shepherd’s dress and with a shepherd’s staff in his hand may be Abel.[76] The prophet-kings, David and Solomon, stand at the other side of the scene in a sarcophagus; they are clad in imperial raiments and crowns, studded with precious stones, like Byzantine emperors.[77] The earliest examples of the composite motif of King David and King Solomon date back to the first quarter of the ninth century and attest to its eastern origin. They figure in the Anastasis representations on the Fieschi Morgan reliquary and (in a mosaic) in the Chapel of San Zeno in the Prassede Church in Rome. The presence of the joint royal portrait in two different images of the Anastasis, in the first quarter of the ninth century suggests that the motif of David and Solomon antedates these works.[78] Behind the kings a bearded man can be identified by his dishevelled hair as John the Baptist, who regularly appears in the Anastasis scene, sometimes in a prominent position. John was preaching in Hades: “Then there came into the midst another, an anchorite from the wilderness and the patriarchs asked him ‘Who are you?’ He replied ‘I am John, the last of the prophets, who made straight the way of the Son of God, and preached repentance to the people for the forgiveness of sins. He sent me to you, to preach that the only begotten Son of God comes here, in order that whoever believes in him should be saved, and whoever does not believe in him should be condemned.”[79] Interest in aspects of the topography of the region where the Anastasis took place was first noted in the early ninth century, mainly focusing on the darkness of the underworld, which is generally placed in the interior of the earth. The scene here is placed between two hills. The meaning of this motif is perhaps best understood in terms of the sceptre cross of Christ. Just as the sceptre rod of Moses divided the waters so the sceptre of Christ shook the earth and tore apart the stones dividing the original single mountain into two hills between which the darkness of Hades stands as evidence of the rending of the earth and the uncovering of the foundation of the world which took place while Christ lay buried.[80]

Not all scenes relating to the Dodecaorton were painted in sequence. Thus Christ’s Ascension has been depicted on top of the triumphal arch. At the top of the west wall, just under the roof, some fragments of a wall painting are visible above a painted scalloped half-round frieze (the fourth row). Although it is not clear what was the original subject of the painting, it may be assumed that they are remnants of the Pentecost, the Descent of the Holy Spirit. The lower part of two rows of men standing in a half-circle can be distinguished, their legs partly covered with chitons, their feet directed to the middle.

Below the half-round frieze some small figures can be seen, but the quality of the paint has deteriorated so badly that the faces can hardly be distinguished. Among them is an emperor wearing almost the same crown as Constantine, the form of the crown usually worn by Comnenen emperors in a later period. The figures appear to point with their hands to what is happening above them. No further explanation can be given about this scene.

The west wall also contains three other wall paintings belonging to the Dodecaorton. They are from right to left the Metamorphosis, the Koimesis and the Baiophoros. The Metamorphosis and the Baiophoros have been discussed earlier.

The relatively large wall painting in the centre relates to the Koimesis (picture 36), the passing away of the Virgin.[81]

Picture 36: Koimesis

She lies on a bier decorated with a cloth. Behind the bier Christ in a mandorla holds the soul of his mother in his arms and looks at her with great sadness. Christ is surrounded by a large number of angels. Michael and Gabriel in imperial garments stand beside him. In the air, two angels, their hands covered by their himation, approach to take the soul of Maria to heaven. Mourning and weeping disciples stand around the bier. Johannes is close to her head; Peter with a censor in his hand is at the side of the bier; Paul in a deeply bowed pose stands at her feet. The other disciples stand around, each in a grieving attitude. Two archbishops in white robes stand beside the angels.

In the third row of the west wall above the scene of the Koimesis Christ has been depicted as the Ancient of Days, enthroned in glory, sitting on a cushion on a richly adorned throne, his feet on a hassock (picture 37).

Picture 37: Christ as Ancient of Days

He makes a gesture of blessing with his right hand and in his left hand he holds a book.[82] He is surrounded by a round mandorla. The throne is richly decorated. Abundant curly white hair adorns his head and beard. He is dressed in a white chiton decorated with clavi and a greenish himation. On each side he is surrounded by three angels, a cherubim, a seraphim and an angel (picture 38-39).[83]

Picture 38: Christ as Ancient of Days, surrounding angels

Picture 39: Christ as Ancient of Days, surrounding angels

The cherubim at the right side has been painted tetramorphically with three heads. The one on the left has one head and holds a long staff in his left hand; the seraphims have six wings, two of which are spread. They both hold long staffs in their hands. The two “normal” angels at the outside kneel before the Ancient of Days. Their fluttering himations resemble those on the angel of the Annunciation.

On the lower row a number of saints have been depicted. Unfortunately many of the figures have decayed or been destroyed over time. In the south-east corner of the south wall three relatively well-preserved paintings of saints can be distinguished. They are from left to right the Slav educators Cyril and Methodius and Cyril of Alexandria (picture 40).[84]

Picture 40: Cyril and Methodius and Cyril of Alexandria

Cyril and Methodius are dressed in priestly garments with the omophorion with three large poloi; each of them holds an evangelarium in his left arm. They are accompanied by Bishop Cyril of Alexandria[85] wearing the phelonion and the omophorion around his shoulders. Additionally there is the epitrachelion and on the sleeves of his right arm is the enchirion. On his head he wears a bonnet,[86] unusually adorned with only one very small trefoiled cross. He makes a gesture of blessing with his right hand and holds an evangelarium in his other hand. Cyril became patriarch of Alexandria in 412. He is famous as the untiring opponent of Nestorius and presided over the Council of Ephesus in 431 at which the teaching of Nestorius was comdemned. He died in 444. He was one of the important Greek churchfathers.

At south wall, a row of seven saints has been mostly preserved. The first two, recognisable by the medical instruments in their hands, are the most venerated physician saints Cosmas and Damian (picture 41).

Picture 41: Cosmas and Damian

heads and part of their chests have been preserved.[87] They each hold a scalpel in their left hand and a medical-chest in the other. Next to them another famous physician Panteleimon has been portrayed (picture 42, left).

Picture 42: Panteleimon and Constantine and Helena

He has a serene face, and a head full of curly hair. He is dressed in a richly decorated tunica. In his right hand he holds a scalpel and in his left hand he too has a medical chest.[88]

Emperor Constantine and his mother Helena stand beside them (picture 42, right). They are depicted together holding between them the Holy Cross that Helena is said to have found when she was visiting Jerusalem.[89] The popularity of the first Christian emperor and his mother as a subject for painters may well indicate a nostalgia for the former greatness and power of Byzantium.[90] They are both dressed in imperial robes richly decorated with precious stones and pearls. Constantine wears the loros and from his spherical crown hangs prependulia. Both figures point to the cross which is decorated with the crown of thorns hanging on the patibulum or transverse beam of the cross. Their faces were most probably painted by one of the more skilful painters. They have large eyes, a small nose and lightly coloured cheeks. Helena looks rather young with a timeless face.

Next to them Joachim and Anna, the parents of the Virgin have been depicted (picture 43).[91]

Picture 43: Joachim and Anna

Joachim stands frontally looking forward holding a scroll in his left hand. He is dressed in a white chiton. Anna is dressed in a dark brown maphorion and holds the young Maria in her left arm while suckling her.[92] The birth of the Virgin is frequently depicted. Usually Anna is shown resting on a bed while midwives are busy with the child. A picture like this where Anna is suckling the new-born baby is rare in Byzantine art. Although probably painted by a less skilful artist, this wall painting is remarkable with its depiction of Anna as aged with sharp lines in her face and greying hair visible from under her maphorion. The little Maria is dressed in the same way as her mother. The maphorions of both mother and child have been defined by a very thin white line.

To the right of the scene of Christ and Maria and John the Baptist on the south wall, there is a fragment of a female figure, dressed in an ochre maphorion which covers her head and body. This could be St. Marina[93] although no mention is made of her name. Hardly anything is known about her. Some identify her with the Marina, a monachoparthenia, a nun who lived in a monastery of men and who dressed as a boy.[94] The fragment shows her head and her right hand in which she holds a double axe, with which she intends to punish Beelzebub.[95] If this is true, this painting is exceptional.

In the west wall is one of the original entrance doors. Around it four rows of wall paintings have been preserved, only somewhat damaged at the lower side. The lowest zone shows three female saints, on each side of the door-opening. There are not very many female saints and to see six on a row is exceptional. To the left of the door, from left to right, are the saints Thecla, Parasceve and Theodora (picture 44).

Picture 44: Three female saints

To the right, from left to right, are Barbara, Cyriace and Catharine (picture 45); they have been indicated by their names. Although none of them has been depicted with the signs of their martyrdom, female martyrs were depicted beside the main entrance as guardians of the church.[96]

Picture 45: Three female saints

Thecla was one of the first females depicted as martyr and is considered to be the arch-martyr.[97] Thecla was a maiden of Iconium, where she heard the preaching of the Apostle Paul and became a Christian. After she had broken off her engagement, her bridegroom and her mother accused her of being a Christian and she was condemned to death by fire. Miraculously she escaped, dressed as a boy, and followed the apostle. Several times she underwent cruel tortures for her faith. Once she was put before wild animals, but they did not harm her. In Iconium she converted her mother. She died peacefully and alone in Seleucia. Here she is dressed in a dark maphorion over a white chiton. She holds an evangelium in her right hand and in the other she holds a small white cross.

Parasceve[98] was the daughter of Christian parents and preached the Christian belief. She was often tortured, but miraculously survived. She succeeded in converting an emperor and preached in nearby countries. She also converted the ruler Asclepius and members of his court, by killing a dragon. Finally she was killed by the sword. She is dressed in the same way as Thecla. In her right hand she holds a white cross and turns the palm of her other hand towards the viewer.

There are a number of female saints bearing the name of Theodora. Most probably the woman depicted here is the nun Theodora.[99] It is said that she was married to Emperor Zeno, but was accused of adultery with a courtier. Therefore she was sent as monachoparthenia to a monastery, where she finally became the abbot. It was only after her death that the monks discovered that she was a female. She is dressed here like a nun in a dark maphorion and around her head a number of veils are cross-wise bound. She stands in orante attitude with both hands raised to her shoulders.

The three women at the right side of the wall have been portrayed in royal dress. They are considered to be queens of the Eastern Church.[100] However, neither canonistically nor hagiographically or iconographically do they belong to a specific group. But usually they are distinguished by their royal dress.

The story of Barbara is well-known. She was locked up in a tower by her pagan father Dioscuros because of her beauty. She espoused Christianity and ordered that, in the bath-house built next to the tower, a third window should be made as a symbol of the Trinity. She explained this symbolism to her father, who accused her of Christianity. She escaped, however, when miraculously a rock opened in which she could hide herself. A shepherd betrayed her, after which she was imprisoned and tortured with whips and burnt by torches. Finally her father beheaded her whereupon he was struck by lightning. Before she died she prayed for all martyrs to be saved from pestilence and death by ordeal. She wears a white chiton and over the chiton a purple mantle attached in front with a round decorated clasp. On her forehead she has a gold diadem that holds a white scarf covering her hair and extending around her neck and shoulders. It is a special garment, named prosoloma that is worn by the daughters of kings and emperors. In her right hand she holds a cross, the open palm of her other hand is turned towards the viewer.

Little is known about the woman saint Cyriace.[101] She was born in Bithynia as a daughter of Dorotheus and Eusebia. During the persecutions under Diocletian she was imprisoned, tortured and killed. She is dressed in the same way as Barbara. Like Theodora, she stands in orante attitude. It is most probably the first time – as far as can be traced – that the saints Barbara and Cypriace have been depicted together and are dressed in the same way, although in later years it became common to do so.

The last female saint is Catherine.[102] She was the daughter of the king of Cyprus and she was tortured in Alexandria at the beginning of the fourth century. At the time this painting was made, her relics had already been enshrined for more than one thousand years in the Orthodox Monastery at the Mountain Sinai that bears her name. She has been depicted wearing a large stemma, an open crown, on her hair. She is dressed in imperial robes. Over a golden yellow decorated chiton she wears a decorated mantle which is framed with a horizontal band adorned with pearls and precious stones. She holds a small white cross in her hands.

Hardly anything has been preserved of the paintings on the north wall. Above the window there is a small painting of the military Saint Demetrius riding a white horse, which is from about the sixteenth century. It is the only painting in this church of a later date, (picture 46).

Picture 46: Demetrius

On the inside of the window in the north wall two saints have been painted. On the left is Onuphrius posed in orante attitude with two raised hands (picture 47)[103]

Picture 47: Onuphrius

He was an Egyptian who lived as a hermit in the desert of Thebais for seventy years. It is said that he was only dressed in his own abundant hair and a loin-cloth of leaves. He has been depicted with very long white hair and a long pointed beard. His body is naked.

On the other side there is a saint whose name has been identified as Euphrosysos or Euphrosinus (picture 48).

Picture 48: Euphrosynos

Nothing is known about the origins or life of this male saint.[104] However, a female saint bearing about the same name, Euphrosyne, is known. Moreover, it is striking that this saint, like Onuphrius, is also known to be from Egypt. According to legend, she was a maiden of Alexandria in Egypt, who lived there as a monk in a monastery. Her sex was not discovered till her death many years later.[105] The figure on the wall painting is dressed like a monk in a dark blue dress wearing a cap in the same colour. From under the cap some curly hair can be seen. He/she has hardly any beard, only some hair on his/her chin. Maybe the painter was not aware of this story.[106]

In the north-east corner below the scene of the Anastasis two saints have been illustrated. One has been identified as Clemens of Ohrid. The portrait is not very well preserved, but the physiognomic features of his face and beard can be recognised. The portrait next to Clemens of Ohrid is of Clement, Pope of Rome, whose relics were discovered by Cyril and Methodius in The Crimea in 863, at the time of their Khazar mission. Clemens of Ohrid was named after Clement the Pope. There is a legend that Clement, Pope of Rome (88-97) was arrested on the orders of Emperor Trajan and sentenced to exile in The Crimea. There he continued his pastoral activity amongst 2,000 Christian miners who were his fellow prisoners.[107] For this he was executed by being tied to an anchor and drowned in the Black Sea. His memory was kept alive by Slavonic teachers and the cult of the saint is exceptionally strong in Macedonia.[108]

His name has been obliterated, but the painting contains all the typological features of the protector of Ohrid. In the history of art this is the oldest portrait of the saint after the one discovered in Sveti Sophia in Ohrid, and as such is of great cultural and historical importance.

The portraits of the two saints are set symmetrically opposite those of Cyril and Methodius on the south wall.

On the outside of the church, some fragments of wall paintings can be seen, although they are in poor condition. In a niche over the south entrance, three figures have been depicted, which form a Deesis (picture 51). Christ is in the middle surrounded by the Virgin at the right side and Djordje at the left.[109]

On the outside of the west wall some remnants of a soldier wearing a shield and a spear can be seen (picture 49).

Picture 49: Demetrius

His name has disappeared, but by comparison with other soldier saints it is supposed that it is Demetrius. On the other side some remnants, of another soldier-saint are recognisable, but it cannot be ascertained with certainty who he is. Most probably it is Djordje.

Thus, Christ Pantocrator on the south wall stands just opposite Djordje, the patron saint of the church, on the north wall. This was planned. Apparently the painters saw conformity in both figures. A similar positioning has been done with the two saints Clemens and Clement who stand opposite Cyril and Methodius. It was Cyril who found the relics of Clement of Rome in The Crimea and took them with him to Rome. The two are, therefore, often associated. Thus, on the triumphal arch of the upper church of San Clemente in Rome a twelfth or thirteenth century mosaic depicts the two saints (pict X 50) while in the lower church is the presumed burial place of Cyril in 869.

Picture 50: Peter and Pope Clement, mosaic from church San Celemente, Rome

The portraits Marina and Euphrosine, the two monachoparthenia nuns, have also been placed opposite each other, although they do not face each other.

A relatively large number of wall paintings have unfortunately disappeared from the walls inside the church in the course of the centuries, but what remains shows that in the Church Sveti Djordje there are a number of remarkable themes which in my opinion have not occurred by chance, but have been well-considered by the painters or their principal(s).

Firstly, there is the careful positioning of certain figures having a particular relationship with each other. Secondly, some scenes are pictured – most probably – for the first time, such as the meeting of Maria and Elisabeth where the two women have been depicted twice, the figure of Marina with an axe above her head; and the depiction of a life-size Christ figure in the paten. Thirdly, there are the strange creatures within Christ’s mandorla in the Ascension scene which have not been repeated in such a way in any other church and for which no reasonable explanation can be given.

Finally, we conclude that, from a close study of the wall paintings in this relatively small church, it appears that the painters or their principal have made well-considered choices on themes and arrangements and have depicted figures and scenes that might have been known in Constantinople or other important Byzantine centres from that time such as Thessalonica, or the nearby located town of Kastoria.

Nicolovski, Antonije, The Frescoes of Kurbinovo, Beograd, 1961; Grozdanov, Cvetan and Hadermann-Misguich, Lydie, Kurbinovo, Skopje, 1992; Hadermann-Misguich, Lydie, Kurbinovo: les fresques de Saint-George et la peinture Byzantine du XIIe siècle, Bruxelles, 1975 ↑

Ljubinkovic, R. in Starinar XV, 1940, p. 101-123 ↑

Manafis, Sinai - Mouriki, Doula, in sub-chapter “Icons from the 12th to the 15th Century”, picture 29, p. 160 ↑

Pelekanides, Stylianos and Chatzidakis, Manolis, Kastoria, Mosaics-Wall Paintings, Athens, 1985, fig. 8 and 9 on page 31 ↑

Manafis, Sinai, p. 108 and fig. 28 on p. 158 ↑

Balabanov, p. 47 mentions three painters by an analysis of the paintings, who differ in both colour and line. He suggests a master and two others. ↑

For a description of the other bishops, see Chapter VIII Sveti Sophia at Ohrid ↑

Lucchesi Palli, E. in LCI 3, p.242-245, s.v. Melismos; Wessel, K. in RbK 1, section B.b, p. 1010-1011 ↑

Walter, Christopher, “The Christ Child on the Altar in Byzantine Apse Decoration”, Actes du XVe Congrès International d’Études Byzantines, Athènes – Septembre 1976, Vol. II, p. 909-913 ↑

St. Matthew 26:26 ↑

Balabanov, p. 47, states that the Kurbinovo painters were the first to paint this scene. ↑

Kaster, K.G., in LCI 6, p.455-457, s.v. Grosser Einzug ↑

The Acts 1:9-11; also Mark 1:19; Luke 24:50-51. The latter mentions Bethany where the Ascension took place; Elliott “The Gospel of Nicodemus or Acts of Pilate”, 16:5 mentions the mountain Mamilch, where Christ was sitting and from where he was taken up; Wessel, K. in RbK II, p.1224-1262, s.v. Himmelfahrt; Schmid, A.A. in LCI 2, p.268-276, s.v. Himmelfahrt Christi; Schiller, Band 3, p.140-164, s.v. Die Himmelfahrt Christi. ↑

Isaiah 66:1 “… The heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool.” ↑

Ezekiel 1:5; Revelation 4:7 ↑

Grozdanov, Cvetan, Hadermann-Misquich, Lydie, Kurbinovo, Skopje, 1992, p.59 ↑

Tatic-Djuric, Mirjana, Das Bild der Engel, Recklinghausen, 1962, p. 37/38 ↑

St. Matthew 16:19 ↑

St. Luke 1:26-38; Elliott, The Protevangelium of James, 11:2-3; Braunfels, W., Die Verkündigung, Düsseldorf, 1949; Wellen, G.A., Theotokos, Utrecht-Antwerpen, 1961, p.37-44; Weitzmann, K., “Eine spätkomnenische Verkündigungsikone des Sinai und die zweite byzantinische Welle des 12. Jahrhunderts” in Studies in the Art at Sinai, Princeton, 1982, p.271-286; Emminghaus, J.H. in LCI 4, p.422-437, s.v. Verkündigung an Maria; Schiller I, p.44-63, s.v. Die Verkündigung an Maria. ↑

The name Gabriel means: My strenghth is God. He is mentioned for the first time in the O.T. in Daniel 8:15 and 16 “… stood before me as the appearance of a man.” And in Daniel 9:21; in the N.T. he is mentioned in St. Luke 1:19 and 26. Lit.: Réau, L. II, p.52-54, s.v. l’Archange Gabriel; Eckhart, T., Engel und Propheten, Recklinghausen, 1959; Tatic-Djuric, Mirjana, Das Bild der Engel, Recklinghausen, 1962; Lucchesi Palli, E. in LCI 2, p.74-77, s.v. Gabriël; Pallas, D.I. in RbK III, p.13-119, s.v. Himmelsmächte, Erzengel und Engel; Timmers, p. 258; Book of Saints, p.232; Davidson, p.117: “Gabriel is one of the two highest-ranking angels in Judaeo-Christian and Mohammedan religious lore. He is the angel of the Annunciation, Resurrection, Mercy, Vengeance, Death, Revelation. Apart from Michael, he is the only angel mentioned by name in the Old Testament. Gabriel presides over Paradise.” – op.cit. ↑

Elliott, The Protevangelium of James, 10:1 ↑

Manafis, Sinai – Mouriki, Doula, in sub-chapter “Icons from the 12th to the 15th Century”, picture 29, p.160 ↑

Maquire, Henri, Art and Eloquence in Byzantium, Princeton, New Jersey, 1981, p.42ff “Descriptions of Spring” refers to a number of metaphors in Greek literature relating to the Annunciation. ↑

Isaiah 11:1-2 ↑

Daniel 11:7 ↑

These pastophoria are used for storing the utensils, the liturgical books and liturgical vestments necessary for the eucharist. ↑

The Acts 6:5-9; Detzel II, p.642-646; Réau III, p.444-449, s.v. Etiene; Nitz, G. in LCI 8, p.395-403, s.v. Stephan, Erzmartyrer; Timmers, p.300. ↑

Painter’s Manual mentions eight holy deacons, of which five should be beardless. ↑