Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Drawing by Natalia Kičeć

On the hill above the town of Ohrid, not far from the Gorna porta, which is the north or upper gate in the old wall that surrounds the town, one can find the Church Sveta Bogorodica Peribleptos, nowadays usually called Sveti Kliment (picture 1-3).

Picture 1: Sveti Kliment, entrance

Picture 2: Sveti Kliment, southern side

Picture 3: Sveti Kliment, view from the north eastern side

The order for the construction and decoration of this church was given by the Byzantine General Progon Zguros and his wife Eudocia in 1295. He was a deputy of the Byzantine Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologos (1282-1328) and related to the latter by a marriage with the daughter of the emperor. An inscription in Greek letters above the main entrance of the church in the narthex reveals their order for the construction. It was built only thirty years after the re-conquest of the Latin Kingdom of Constantinople in 1261 by the dynasty of the Palaeologen, during the reign of Archbishop Makarije of Ohrid.

Its original name is Sveti Bogorodica Peribleptos, which means Our Lady the Most Glorious, under which name it is known best in academic circles. At the end of the fourteenth century Ohrid was conquered by the Osmanli Turks. Instead of building their own religious centres the Turks found it easier to transform existing Christian churches into mosques. Consequently the Church Sveti Sophia, the archiepiscopal church of Ohrid, became a mosque. Some time later, at the end of the fifteenth century, Clement’s old foundation, Sveti Panteleimon (built by him in 893), was partly broken down and on the same place a mosque was built. The saint’s relics, after having been temporarily interred in another church, were transferred to the Sveti Bogorodica Peribleptos, and since that time the second name of Sveti Kliment was given to it by the population of Ohrid. In 1943 during archaeological excavations inside the Imaret Mosque the foundations of the old Church of Sveti Panteleimon were discovered and also the original place of Kliment’s tomb.[1] In August 2002, the saint’s remains were re-buried in the new cathedral built at Plaosnik.

In the absence of a main church for the archbishopric the Sveti Bogorodica Peribleptos became the cathedral and the see of the archbishops who succeeded in maintaining their power during the greater part of the Turkish occupation. A monastery complex was built around the church as well as a palace for the archbishop nearby. Both were burnt down in the nineteenth century.

Many religious treasures of the churches, which had been confiscated by the Moslems, were brought to this church including icons, hand-written manuscripts, eucharistic vessels and the oldest music notations of Byzantine Church singing in Macedonia. The greater part of the icons is now in a museum opposite the church.

Architecturally the church is not very large. It is a domed cross-in-square church with a central cupola and a narthex on the west side. The church itself has a length of about 17 metres. It is built of alternating layers of stone, bricks and mortar, laid in such a way as to give interesting compositions of chess-fields and crosses, which can best be seen at the rear of the church (picture 4).

Picture 4: Sveti Kliment, view from the eastern side

Two separate annexes were built onto the church in the fourteenth century. Their construction differs somewhat from the rest of the church. From the outside it looks as though they function as diaconicon and prothesis. However, it is not possible to enter them from the bema. In the south and north wall of the naos a door leads to the exo-narthex and from there one can enter the annexes (parekklesia). The exo-narthex was built around the church, starting at the annexes, encircling it until the present day. The exo-nathex, which was constructed as an open porch in the fourteenth century, changed the picturesque aspect of the church considerably. The main entrance to the exo-narthex, the narthex and the church itself is on the west side at the top of a flight of steps. The roof above the entrance rests on a number of pillars, which are apparently reused spolia from Roman times.

The interior of the church is completely covered with wall paintings which have been almost entirely preserved although, under the influence of calcining, some flaking has occurred especially in the higher parts. The wall paintings are remarkably bright. The sequence of the paintings differs somewhat from that in other churches. The paintings belonging to the dodecaorton have been mainly painted on the barrel vaults of the cross arms of the church. The painters have paid special attention to the passion of Christ, to be found in the third row. It is no surprise that a church dedicated to the Virgin contains a series depicting her life. The painters have made a series of at least fifteen different scenes in the second row, some of which have been made for the first time. The painters have filled a few unused places on the walls with some scenes from the life of Christ. The lowest row contains, as usual, a long line of different saints while others can be found on the pillars supporting the cupola. The separate narthex contains a number of remarkable paintings.

In this church the painters did not wish to remain anonymous but have incorporated their names in a number of the paintings. This practice is not very common: usually there is an attempt at concealment, for example the folds on a sleeve or the glistering of a sword may appear as letters. The paintings here were made by Michael and Eutychius,[2] who most probably came from Thessalonica. Another name, Astrapas, has also been found, but academic opinion is divided on whether it is that of a third painter. Astrapas may have been the family-name of one or both of the painters.

It seems likely that Michael and Eutychius worked on the painting of the church along with a team which was comprised of assistants and apprentices.[3]

The painters in this church used a new style of painting, called the Palaeologan Renaissance. It is generally accepted that this style started about the year 1265 in the Serbian church at Sopoćani where it served as a model for many other churches in the Byzantine sphere of influence.

The style of painting of Michael and Eutychius differs from previous periods and could even be described as anti-classical[4]. Their compositions have been shaped magisterially. There is certainty in their drawing and freshness in their colouring. There is no earlier example of their rather individual way of painting, which shows fine expression in the faces, soft and delicate with the women, forceful with the men, who have full cheeks and athletic bodies with strong necks. The figures are linear, but in some instances spectacularly voluminous, or even bulky. The painters had a predilection for extensive narrative scenes with a large number of people. In these dramatic scenes the faces are full of sorrow or fear, with expressive movement of hands and raised arms. The paintings reveal attention to small realistic details, graceful and new.

Most of the scenes are not bordered with lines but overlap. The figures at the edges of a painting could equally well belong to the adjacent painting. The stories rendered are not defined but form a continuing narrative. The painters have systematically created a number of cycles relating to christological scenes about the life and death of Christ, apocryphal scenes about the life of Maria and Old Testament prefigurations of the incarnation of Christ, all of which will be discussed more extensively below.

The calotte of the cupola contains a painting of Christ Pantocrator inside a medallion (picture 5).

Picture 5: Cupola, Christ Pantocrator

On the white circle surrounding the medallion words have been painted. In his right hand He holds a jewel studded book and with his other hand He makes a gesture of speaking. Six floating angels with outstretched hands hold the medallion. Beneath them, between the four windows of the octagonal tambour, life-size figures of prophets have been painted in groups of three. On the four pendentives supporting the tambour and the cupola the evangelists have been painted in the act of writing their gospels, Matthew on the south-east pendentive, Mark on the south-west, Johannes on the north-east and Luke on the north-west. The paintings have not been well preserved.

The paintings in this church that attract most attention are those seen when entering the apse. The view of the paintings (picture: wall paintings in the apse, photo by Blagoja Drnkov is missing) shown here is, however, now obscured.

It was photographed during the time of the former socialist republic before the Republic of Macedonia became an independent state and the churches were given back to the Macedonian Orthodox Church. This church is now in use again as a place of worship and an iconostasis placed between the bema and naos hides most parts of the paintings from view. The splendid wall paintings, fortunately, have been saved entirely.

In the half cupola of the apse Maria has been depicted (picture 6) standing on a suppedium with her hands raised in an orante attitude, her palms open towards the viewer, a so-called Mother of God Blachernitissa.[5]

Picture 6: Maria

This name goes back to a similar depiction in the Blacherne Church in Constantinople, which is most probably of Syrian origin. This way of showing the Virgin was popular before the time of iconoclasm, but after that period more preference was given to other forms of depictions. She is the intermediary between the faithful and Christ Pantocrator. The faithful are shown in the church below Christ’s picture in the cupola.[6] Maria is dressed in a purple maphorion over a light blue chiton. She is painted against a blue background symbolising heaven, while the suppedium rests on green ground: symbolising the earth.

Below this scene the Communion of the Apostles has been painted. Christ has been depicted twice, standing behind an altar table covered with a red cloth embroidered at the corners and the hem, and at the front with a cross (picture 7).

Picture 7: Apse, Communion of the Apostles

He stands under a ciborium which rests on three decorated pillars. To the left and right two rows of disciples wait for the metadosis and the metalepsis. On the left Christ takes bread out of the paten and gives it to the first apostle in the row (metadosis).

This is most probably Peter to judge by his physiognomy. Five others stand behind Peter in the same attitude, a little bent in supplication, except for one who stands erect with his arms crossed over his chest looking at the viewer. On the right the others await for the chalice of wine which Christ offers to the first in the row (metalepsis) . Usually this would be Paul, but here another apostle, possibly Johannes, has been depicted. They have covered their hands or are busy hiding them in their himatia. On the far right, two are in conversation. Christ is assisted by two angel deacons dressed in white tunicas, each holding a flabella in their hands. The background of the scene shows some houses. Christ is clothed in a purple chiton under a blue himation, which he wears over his left shoulder. The clothing of each of the apostles is of a different colour and sometimes two colours are used giving a freshness to the colouring, for which the painters of this church are known.

Below this scene a row of seven bishops can be seen, painted in half length (picture 8).

Picture 8: Five bishops

They are from left to right: Germanos I, Tarasios, Methodios, three bishops of Constantinople, Jacobus (James), brother of Christ and the first bishop of Jerusalem, Sylvester and Clemens, both popes of Rome and Bishop Metrophanes of Constantinople. They have been identified by name. [7] The saints are all dressed in exactly the same way with a polystaurion and an omophorion. Each of them holds a richly decorated book in his hands, except Bishop Jacobus, who is only partly visible because of a window in the apse.[8] Little is known of Germanos I and Tarasios. Bishop Methodios I, known as the Confessor of Constantinople, has been depicted with a bandage on his head. This bandage, decorated with a cross, was placed there to support his broken jaw. The iconoclast executioners have disfigured Methodius.[9] Pope Sylvester (314-335)[10] has become known from a fifth century legend which tells that he baptised Constantine the Great (306-337), most probably because both leaders were active in their respective functions at almost the same time. The life of this pope is depicted in a series of wall paintings in Rome in the Chapel of Sylvester, which is part of the Santi Quattro Coronati, painted in 1246. One of them shows Constantine the Great in a submissive position handing over to Pope Sylvester the tiara as the leader of Christendom. It is a fictitious and misleading illustration in support of the idea of Roman Catholic rule over all Christians in the world.

About Bishop Metrophanes of Constantinople hardly anything is known.[11]

The row of bishops depicted in half length in the apse, below the Communion of the Apostles, continues on the north and south walls. On the north wall the bishops Dionysius the Areopagite,[12] Hiërotheus of Athens,[13] Michael Homologetes, Eutychius of Constantinople[14] and Paul Homologetes[15] have been painted.

On the south wall the bishops John the Almsgiver,[16] Meletius of Antiochia,[17] Epiphanius of Constantia from Cyprus,[18] Andrew from Crete, archbishop of Gortyna and an eminent poet[19], and probably Amphilocius of Iconium[20] are portrayed (missing picture).

Below the row of busts of bishops in the half cylinder of the apse, four officiating bishops have been shown. The two on the left, Basil the Great followed by Gregory of Niazanz, turn to the right (picture 9), while on the other side Ioannis Chrysostomos and Athanasius of Alexandria turn to the left (picture 10).

Picture 9: Bishops Basil the Great and Gregory of Niazanz

Picture 10: Bishops Ioannis Chrysostomos and Athanasius of Alexandria

They have been painted as robust figures and have heavy long beards, except for Ioannis, who, like Athanasius, has been portrayed as almost bald. All four wear richly adorned poloi on the omophorion and a polystaurion, which are completely structurally covered with multicoloured poloi. They stand in three-quarter pose. An enormous and very heavy chair has been put before them in this scene. What they are celebrating or attending is not clear, although it may be a Eucharist with a Melismos, the Christ-child lying on the paten.[21] They are dressed in the same way as the bishops depicted above them. Each of them holds an unrolled scroll in his hands. Basil the Great holds a scroll with the translated Greek text: “None of them who are bound by fleshly lusts is worthy”[22]. Gregory of Niazanz’ scroll carries the words: “Master, our Lord, you who has drawn up the lines in heaven”[23]. The text of Ioannis Chrysostomos is: “You who has given us common and unanimous prayers”[24] and that of Athanasius the Great is: “Lord, our God, whose power is incomparable and the glory”[25].

On the walls of the bema other bishops have been depicted, together with the bishops in the apse forming a so-called Great Entrance.[26] Since most of their names have disappeared they can no longer be identified. From left to right on the north wall are two unknown bishops. The second one is wearing a beehive head-dress.[27] He is followed by another unknown bishop with Gregory of Nyssa in the corner.

On the south wall are the bishops Gregory Thaumaturgos and Antipas together with another unknown bishop[28] (picture 11, is this the correct image because the unknown bishop is missing).

87

Picture 11: Bishops Gregory Thaumaturgos and Antipas

On the north-east pillar, just behind the iconostasis, St. Nicholas has been depicted (picture 12) and on the south-east pillar there is a rendering of Cyril of Alexandria (picture 13).

Picture 12: Bishop Nicholas of Myra

Picture 13: Bishop Cyril of Alexandria

The scroll of St. Nicholas carries, in Greek, the words: “So as under your power we are always protected, we glorify you”. The scroll of Cyril of Alexandria carries the text: “Exception made to the Virgin, the most immaculate, the most blessed”.

The triumphal arch contains a large number of medallions. At the top in the middle a youthful beardless Christ Emanuel has been illustrated, flanked on either side by the archangels Michael and Gabriel. The long row continues with ancestors of Christ. This includes a number of crowned heads and bearded saints, among a relatively large number of judges. Christ has been depicted on a yellow background. The background of the respective medallions is alternately yellow or red.

On the wall to the left of the triumphal arch Archdeacon Romanos de Melode[29] has been shown and on the other side is Deacon Stephen, the first martyr.[30] There is a legend that one day the Virgin appeared to Romanos in the Blacherne Church in Constantinople. It is generally accepted that the Akathistos hymn was created by him. Opposite Deacon Romanus, Deacon Euplos has been depicted on the north-east pillar and Deacon Laurentius is opposite Deacon Stephen on the south-east pillar.

On the side walls of the bema and on the ceiling there are a number of scenes relating to the dodecaorton, which will be dealt with later.

The Annunciation is usually depicted on the wall beside the triumphal arch, but because of the lack of space, the scene has been painted here on the southern cross arm. It will be discussed later in connection with the long and interesting cycle of paintings relating the birth and life of the Virgin.

The scene of the Birth of Christ (picture 14) has been painted on the ceiling of the southern cross arm of the church.[31]

Picture 14: Birth of Christ

The painting is somewhat flaked on the lower side, but it clearly reveals the events that are taking place. In the middle of the scene the Virgin sits rather than lies on a mattress with a large number of figures circling around. She appears to be looking at what is happening on the right. She is dressed in a blue maphorion and her left hand rests on her leg. Behind her in the cave lies the Christ-child in a manger, his head close to his mother. The ox and donkey stand behind the manger. Just above the entrance to the cave a star projects a beam of light from heaven. At the top angels are praising God, and on the right an angel bends towards two shepherds to announce the birth. The younger of the two looks up to hear what the angel is telling him. Just above the cave one angel points with his hand to the Child. On the left of the scene another angel addresses himself to the three wise men who approach led by the star. At the bottom, which is badly flaked, Joseph can be distinguished sitting on the left side looking at the bathing of the Child; Joseph has been depicted rather voluptuously. On the right the midwife can be seen bathing the Child. Between Joseph and the midwife another figure can be seen, but it is no longer possible to discern whether it is a midwife or a small boy who is in conversation with Joseph.

The Hypapante has been painted on the ceiling of the same arm opposite the Gennesis. The scene is in poor condition caused by calcining (picture 15).

Picture 15: Presentation of Christ in the temple

On the left are Joseph, who holds two doves, and Maria, who carries the Child. It is unclear what the Child is doing. On the right are Simeon and the Prophetess Anna. Simeon has covered hands outstretched towards the Child. Both Maria and Simeon stand before a ciborium.

As already stated the scenes relating to the Dodecaorton have not been depicted in a continuous sequence. The Baptism of Christ has been painted on the barrel vault of the north arm (picture 16).

Picture 16: Baptism of Christ

The River Jordan streams through a cleft formed by huge mountains on either side. On the left of the scene Christ and John the Baptist stand opposite each other in a hollow in the mountain and discuss who is to be baptised;[32] it looks as if Christ is baptising John. In the centre the undressed Christ stands in the water up to his head. John stands on a rock on the left bending deeply in order to baptise Christ. From heaven, symbolised by a white circle with a blue centre, beams of light radiate and one beam focuses on the head of Christ. In the middle of the beam a dove is shown as the symbol of the Holy Ghost. In the blue centre of the circle the hand of God points down to his Son. On the right seven angels, their hands covered by their himations, stand waiting. The painters in this church have a preference for extensive scenes and have consequently included more than the usual two or three angels. On the left bank of the river the Personification of the water holds a large stone bottle from which the water flows that feeds the river. Children play and swim in the water and a small boy sits on the left looking at his friends. Somewhat below John a tree can be seen and at its foot lies an axe. “…the axe is laid unto the root of the trees: therefore every tree which bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire.”[33] The representation of an axe at the foot of a tree originated in the Middle Ages. One of the earliest examples is a mosaic which can be found in the katholikon of the Monastery Hosios Loukas from the eleventh century.

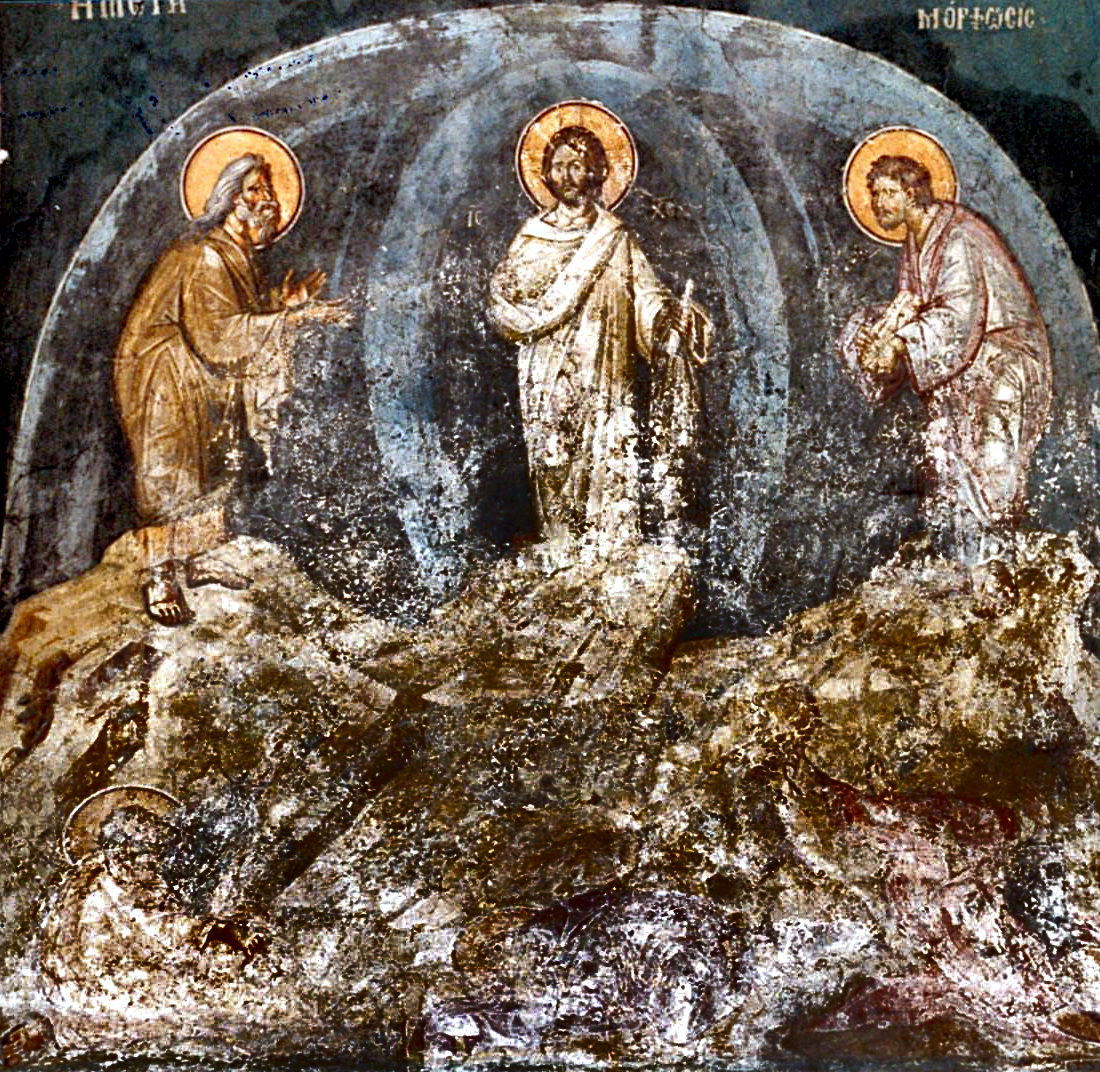

Opposite, on the barrel vault of the same cross arm there is a depiction of the Metamorphosis of which only the upper part has been preserved (picture 17).

Picture 17: Methamorphosis

It shows Christ in a mandorla standing on the top on a mountain making a gesture of blessing. Elias and Moses are on the right and left, respectively. Three accompanying disciples can be seen very indistinctly at the foot of the mountain.

Below these scenes the Raising of Lazarus (picture 18-19) has been illustrated on the north wall at the end of the cross arm.[34]

Picture 18: Raising of Lazarus

Picture 19: Raising of Lazarus

The painters have ingeniously made use of a window in the wall by depicting the scene on both sides of it and including the background of a mountainous landscape around the window. On the left of the scene, Christ, in a purple chiton and a blue himation, is followed by a number of his disciples. Four faces are visible. Christ stretches his right hand towards Lazarus, as if saying: “Lazarus, come forth.”[35] On the far right a man is on his knees ready to put down the heavy lid of the sarcophagus. Lazarus stands upright in the open sarcophagus which has been depicted inside a cave. He is completely bound in grave clothes, except that his face that is covered with a napkin. He is looking at Christ. To his left a man is busy loosening the grave clothes from his body, in accordance with the words of Christ: “… Loose him, and let him go.”[36] The man holds one hand to his nose against the smell. In front of the sarcophagus the sisters Martha and Maria are, with covered outstretched hands, in proskynese before Christ. In the background a number of Jews observe what is happening. One of them holds a lamp in his hand. The painters have succeeded in depicting, in great detail, the story as told by the Evangelist Johannes. The faces look serious, impressed by the sorrowful event. The disciples look at each other with gesticulating hands as Christ moves towards the tomb. The sisters look up at him in anticipation, while the Jews deliberate whether they should inform the Pharisees.

A complicated wall painting not belonging to the series of the Dodecaorton can be found on the north wall (picture 20).

Picture 20: Scenes with Christ

The painters have tried to depict a number of successive scenes, with the result that the figure of Christ has been painted three times in close proximity. Although the colours have disappeared on the left, the surviving part of the wall painting shows Christ seated. In his left hand he holds a scroll and at his feet stands a bottle and a vague figure can be noticed in front of him. The next scene in the centre shows Christ standing and a woman with raised hands in supplication in front of him. With his right hand He makes a gesture of blessing. Behind him three men can be noticed without nimbi and behind that group Christ again and two men with nimbi. In my opinion this is a depiction of the story told by Luke.[37] Christ was invited to come to the house of one of the Pharisees, named Simon, who desired that he would dine with him. A woman in the city, known for her sins, knowing that He would eat in that house, came in, bringing with her an alabaster box of ointment. With her tears she washed his feet, wiped them with her hair, kissed his feet and anointed them. That part of the painting is unfortunately no longer visible. The next scene shows Christ blessing the prostrate woman, saying that her sins are forgiven. The middle part shows the Pharisees talking to Christ, wondering whether He as a prophet should know about the woman, whereupon Christ tells them a short parable. The top of the scene shows Christ again reproving two men, one of them may be Judas Iscariot, who is complaining about the waste of money that could have better been given to the poor.[38] The Gospels reveal other women anointing Christ. Since the time of Gregorius I [39] one is identified in the West as Maria of Magdela.

On the right side of the wall painting Christ, followed by his disciples, meets a woman who had been crippled for eighteen years. She was bowed down, and could not lift herself up.[40] Christ laid his hands on her and immediately she was made straight.

On the west side of the northern barrel vault, the Entry into Jerusalem has been painted.[41] The surface of the painting is very badly calcined. In the left hand corner one of the disciples, leading two colts is shown leaving a house standing behind a mount. In the middle of the scene Christ seated on a colt and surrounded by his disciples rides to the right, descending the mount. He looks back in the direction of the gate of Jerusalem where a crowd of people await him. Two children are busy cutting off branches from a tree while others are spreading their clothes on the road.

In the middle of this ceiling there is a painting of the Ancient of Days surrounded by a three-coloured mandorla[42] (pict. XI 21). It is remarkable that the Ancient of Days has been depicted without a cross in the nimbus and without the abbreviation IC XC, or any angels or other figures that usually surround him. A few years earlier such a depiction would not have been possible, but most probably under western influence (the occupation of Constantinople by the Franks ended in 1261) God the Father rather than Christ, has been pictured as the Ancient of Days. This is one of the first examples in Macedonia. The artist has succeeded in painting a timeless face, surrounded by grey hair, beard and moustache. His eyes look benevolently but attentively at the people on earth whom he blesses with his right hand. He holds a closed book on his left arm. He wears a brown rather than a white himation over a white chiton.

On the north wall Christ is shown cleansing the temple by casting out all those who were selling, buying and money-changing[43] (pict. XI 22). “And when He had made a scourge of small cords, he drove them all out of the temple …”[44] The painting shows Christ on the left, with a long rope running towards the merchants. The centre of the wall painting is damaged and calcined, but it is still possible to see overturned tables and the people running away taking their merchandise with them. The architecture in the background suggests the temple.

In the Gospel of John reference is made to the words of Christ: “… Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up”, words that were used against Him after His arrest.[45]

The painters have paid more than usual attention to the Passion of Christ.[46] It is not known whether or not they did so on the instructions of General Progon Zguros, who commissioned the building of the church. More likely they were advised by the Archbishop Makarije of Ohrid, during whose reign the church was built. In any event it is almost certain that they worked according to a well devised plan and did not have a free hand to do what they liked.

The series based on the Passion of Christ starts with the Last Supper or Mysticos Deipnos[47] (pict. XI 23). The painting has been done on the south wall partly in the bema, partly in the naos. Scenes like this are not frequently portrayed and most of the time the Communion of the Apostles, which much better expresses the meaning of the Eucharist, is preferred. In this church, however, both scenes have been done. The scene of the Last Supper has generally no fixed place in the church, although one might expect to find it in the bema. When it forms a part of the Passion sequence it could be located in various places. In the background some architecture has been painted suggesting a closed room. In the centre stands a large round table on which there are a plate for the bread, some decanters and glasses for the wine, pieces of bread, vegetables and some knives. The disciples recline around the table, lying on the stibadium, talking to each other. In the centre of the background Christ has been depicted, holding a scroll in his left hand and with his right to his chest. Johannes, the youngest of the disciples, is bending towards him, raising one hand in a gesture of speaking, as if he wants to convince Christ of something. In the foreground Peter reclines alone. On the right Judas stretches out his hand to take a piece of bread from the plate; he has been depicted en profile which has a negative meaning. Moreover, Judas is the only one who has been depicted without a nimbus.

The mosaic in the Church of Apollinare Nuovo at Ravenna is considered to be one of the oldest depictions of the Last Supper. It shows the old fashioned way of reclining at the table with the attendants serving on the left. From the view of the observer the place of honour was seen on the left. In the wall painting of this church only Peter reclines in the old fashioned style, leaning with his left arm on the table.

Much older wall paintings in the catacombs are sometimes considered to depict the Last Supper, although if indeed they have a Christian meaning, the paintings relate to image signs like the miracle of the feeding of the five thousand, or the Wedding at Cana. It is a very old custom to serve a meal after the burial of the deceased and it is understandable that such a depiction was painted in a catacomb as a remembrance. Those who planned the mural paintings in the catacombs were probably not entirely averse to a certain ambiguity in their image-signs, since the feeding of the five thousand, for example, was regarded as a symbol of the agapae of paradise or a figuration of the Last Supper.[48]

On the wall of the southern cross arm a poorly preserved wall painting depicts the Washing of the Disciples’ feet[49]. Christ standing at the left side of the scene is busy washing the feet of Peter in a round basin that resembles a baptismal font. The latter sits on a bank, the other disciples behind him; Peter’s sandals are on the ground in front of him. The poor quality of the wall painting does not allow an extensive description.

At the end of the southern cross arm one can find a beautiful and impressive, narrative picture of the Prayer at Gethsemane,[50] which forms part of the Passion of Christ (pict. XI 24). It consists of three episodes. At the top in the middle of the scene, Christ, dressed only in His chiton, kneels with His face to the ground saying His first prayer: “O my Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me, but not as I will, but as you will.” On the left He stands again in agony, one hand held out as in supplication, the other at His chin, praying his second prayer: “O my Father, if this cup may not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done.” The text of his prayers has been painted on the wall. He has cast his himation before Him on the ground. Two pairs of angels from heaven fly behind to support Him. On the right He comes back to the disciples, and asks them why they could not watch with Him for one hour.

The mountain is bare except for some clusters of trees and bushes. In the foreground the weary disciples sit or lie in different poses. Some are yawning while others are still fast asleep. Some of them are wrapped in their himatia. In the foreground one disciple lies on the ground in a recumbent position with his head resting on the body of another one, while another lies with his head on the body of the disciple in the foreground. In the centre one of them is awakening his neighbour. Peter, with his back to the viewer, and Johannes have just woken up. Peter’s hands suggest apology for their falling asleep, while Johannes, who sits opposite him on a piece of the rock, makes movements with his hands as if speaking to Peter. Each of the men wears garments of a different bright colour and the folds have been modelled to indicate exactly their pose. The linear slender figure of Christ is in contrast to the somewhat voluptuous depiction of the disciples. The poses in which the painters have shown the sleeping disciples are lively and natural, demonstrating the high quality of their craftsmanship. They have also succeeded in the use of perspective foreshortening in the depiction of some of the figures, one of the first examples of this technique in Byzantine art. The technique was not repeated again for about one hundred years: it can be seen in a corresponding wall painting in Sveti Andreas[51] and in northern and western countries.

On the west side of the southern cross-arm the Betrayal of Judas and the capture of Christ, called the Prodosia, have been painted[52] (pict. XI 25). The upper part of the wall painting has been preserved but is in bad condition. Christ stands in the centre, holding a scroll in his left hand; Judas, standing to the left of Christ, embraces him by putting his right hand on Christ’s shoulder and kisses him. The face of Christ is grave; He is not looking at Judas but at the observer in the church. The face of Judas has been pictured en profile to express the negative significance of what he is doing. All around them circle a mass of people with grim faces; soldiers with drawn swords come nearer to arrest Christ. In the corner at the right side Peter has seized Malchus the servant of the high priest[53] and is in the act of cutting off his ear. In the background on the left, the other disciples are pictured fleeing.

At the west end of the south wall there are a number of scenes relating to the Passion of Christ, including Christ before High Priest Caiaphas (pict. XI 26), followed by the denial of Peter, the mocking and, in the corner, Christ before Pilate.

In the first scene Christ, His hands bound, stands before a table covered with a pink cloth, on which lie a book, a pencil and a piece of paper containing the accusation. Behind the table the High Priest Caiaphas sits together with the scribes and elders, who are questioning Him about His doctrine (pict. XI 26 left).[54] A man in front of Christ raises his fist to punch him. All around Christ soldiers and a number of people look and listen. In the corner on the left a man has been painted who is looking from afar, one hand raised in astonishment towards a maid who is pointing at him. This is Peter who followed Christ and was present in the high priest’s palace. On the right Peter sits near the fire to warm himself. A servant behind him and other servants around the fire point at him, saying that he was one of the followers. But Peter sitting there in an attitude of innocence looks amazed at the people opposite him and he denies his association three times. Then a cock crows and Peter remembers the words of Christ.

The scenes overlap and continue with a group of Jewish priests behind Christ who are accusing Him before Pilate, the Roman governor. Pilate stands behind a table washing his hands and says: “I am innocent of the blood of this just person.” The painters have deliberately paid much attention to the hands of Pilate.

The passion cycle continues on the opposite north wall with the Mockery of Christ (pict. XI 27). “Then the soldiers of the governor took Jesus into the common hall, and gathered unto him the whole band of soldiers. And they stripped him, and put on him a scarlet robe. And when they had platted a crown of thorns, they put it upon his head, and a reed in his right hand: and they bowed the knee before him, and mocked him, saying, Hail, King of the Jews!”[55] In this scene Christ stands in the centre surrounded by a crowd of people. Some are kneeling in front of Him. On the left a man is seen playing a drum. It must be assumed that this scene relates to the second mocking.

The slightly calcined wall painting continues by showing Christ with hands bound walking beside Simon of Cyrene who was compelled to bear the cross (pict. XI 28). Behind Christ some women are following. The cortège arrives at the already erected cross where Jewish priests with long white beards and other people await the execution. In front of the cross a man holding a large chalice attempts to give Christ vinegar to drink, but he has turned his head away and looks at the viewer.[56] Christ is dressed in a collobium. One man stands on the cross doing some work and at the foot another man is busy hammering wedges between the rock and the cross to support it. This small scene, which has seldom been pictured in this way, reveals more than words can say, and shows the resourcefulness of the painters who have succeeded in expressing and combining the events told by the evangelist.

The cycle continues inside the cross arm with a scene that so far has not been depicted. Christ naked but for a sublicagulium, or loin cloth, takes a large step to climb a ladder that has been put against the cross (pict. XI 29).[57] On the left the Jewish priests and people look on. The first man in the row points his finger at the cross. Beneath the cross three men look at two soldiers throwing dice for the clothing of Christ. One of them has a drawn sword in his hand.[58] In the distance on the right the mother of Christ and Johannes look shocked at what is going on. It is possible that the painters may have seen a similar scene before in Constantinople, or elsewhere, and have applied their experience in this church. It is, as far as I know, the first time that such a depiction has been painted in Macedonia.

The Crucifixion itself shows a dead Christ hanging on the cross, His head resting on His right shoulder.[59] The wall painting is calcified somewhat on the centre and on the right side. Consequently it is not quite possible to see exactly what has been depicted. His arms are slightly bent; His contorted body is naked except for a sublicagulium. His feet have been nailed to the suppedaneum. From His feet blood drips onto the skull of Adam which lies in a hole in a mountain-like place beneath the cross. On the left two women can be distinguished, the first of them is Maria, his mother; on the right Johannes stands in deep grief.

One of the most dramatic and beautiful scenes in this church is the Lamentation of Christ, the Threnos, which can be found at the north end of the cross (pict. XI 30). Two features of the painting are of particular interest. First, Christ is lying on a stone, the so-called ointment stone, or lithos.[60] There is a legend that after the death of Christ He was laid on a flat stone to be embalmed and His body prepared for laying in the sepulchre. Full of sorrow at Christ’s death, Maria of Magdala went to Rome to accuse Pontius Pilate before Emperor Tiberius for his part in the death of Christ. As proof she took the ointment stone with her as far as the harbour of Ephesus. On this stone the marks of the tears of the Virgin had remained unwashed and were still visible “white as milk”.[61] The stone was kept in the church of Ephesus until it was brought to Constantinople, most probably in the year 1170, by Emperor Manuel I Comnenos (1143-1180). He is said to have carried it on his shoulders from Ephesus in a solemn procession recalling the procession of Simon of Cyrene who carried the cross of Christ. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 the stone was lost. Only after the date of its arrival in Constantinople did the stone begin to be pictured in lamentation scenes. The scene in this church shows Christ lying on a cloth that covers the lithos, naked except for the sublicagulium around his waist, in which he was crucified. Johannes in a sombre pose holds, with both hands, the right hand of Christ to his mouth. Joseph of Arimathea kneels at the far end of the lithos as if he is intending to wrap the feet of Christ in the cloth; next to him stands Nicodemus.

The second feature of interest is that Maria does not lament with the dead body of her son in her arms as the scene is usually depicted, but she looks up, supported by other women, as if she is no longer able to bear her sorrow. On the right behind the head of Christ, one standing woman has in deep sorrow loosened her hair and her face bears an expression of deep anguish. It is most remarkable that the painters have shown deep human grief in such a way. Such detailed emotion had never been seen before. It is possible that she is the woman who washed the feet of Christ with tears and wiped them with her hair and anointed them with ointment.[62] This woman may have been Maria of Magdala. A large number of wailing women standing or sitting around and behind the ointment stone in all kinds of postures express their sorrow at the death of Christ. Remarkable is the woman at the back who has raised her arms. It is this detail that gives the composition as a whole its dramatic effect. Three groups of three small angels float in the air, one of them is holding his hands to his mouth to express his grief. At the corners two large individual angels with outstretched hands look down at what is happening on earth. In front of the scene the painter has depicted the arma christi, the thorn-crown, a basket with the nails, the vessel with vinegar and two sticks with the sponge and the spear, respectively. It is in such scenes that the painters could express their craftsmanship, showing in particular their preference for large groups.

On the south wall, at the right side of the arm of the cross, the Anastasis has been painted[63] (pict. XI 31). This painting has also been somewhat flaked by calcination, but the main features are clearly visible. Christ, in a descending movement, leans forward to pull, with his right hand, Adam out of his sarcophagus. In his left hand He holds a scroll and He stands on the broken doors of Hades. He does not hold his cross triumphantly in his hand as usual, but instead the painters have extended the cross in his nimbus with light beams to suggest a large cross behind him. Behind Adam stands Eve in a red maphorion and beside her Abel has been depicted. On the right the prophet-kings David and Solomon in imperial garments with crowned heads are talking to each other and behind them John Prodomos points with his right hand at Christ. In the background two mountains have been painted.

To the right of this scene the Women at the Empty Sepulchre have been depicted (pict. XI 32). At the lower side two myrrophores can be seen standing before an angel with wide outstretched wings, who sits on a stone pointing at the empty sarcophagus with the grave clothes. The two women at the empty sepulchre are usually identified as Maria of Magdala and the other Maria. At the upper side the two women kneel before Christ, who in turn stands somewhat higher up the slope of a hill. At first they are unaware that it is the Lord. “And as they went to tell his disciples, behold, Jesus met them, saying, All hail. And they came and held him by the feet and worshipped him…”[64] Christ points with his right hand as if He is saying: “Go tell my brethren that they go into Galilee, and there shall they see me.” In the corner on the right there are the keepers of the sepulchre, who for fear of the angel shake and become as dead men. They are huddled together hiding behind their shields, their spears standing upright between them. Two huge rocky mountains rise up in the background.

On the north wall of the bema there are two depictions of the Appearance of Christ to His disciples. On the left Christ stands on a flat stone before them and blesses them with His right hand while holding an unrolled scroll in His other hand (pict. XI 33). It carries the Greek text, which in translation reads: “…All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth”.[65] It is remarkable that Christ does not appear in a closed room or at the Sea of Tiberias but somewhere outside.[66] Peter, the first in the row of the disciples, has stretched out his hands in supplication.

This relatively small scene flows into to the next scene, the doubting of Thomas (pict. XI 34).[67] Christ stands before a closed door inside a house. On the right and left there are two groups of six disciples. Christ has raised His right arm and shows Thomas the wound in His side. Thomas with an outstretched right arm has put his finger there. All the disciples are looking at Christ and Thomas.

The Ascension of Christ or Analepsis can be seen on the ceiling of the bema (pict. XI 35)[68]. In the centre Christ and two angels together in one mandorla against a blue background are being carried upwards to heaven by four angels. Christ is standing and makes a gesture of blessing with both hands. He is dressed in a gold shining chiton and himation. The two angels bow slightly towards him with open hands as if they are intending to carry him. Each wears a blue chiton and a purple himation. Their wings follow the downwards curve of the mandorla. The heads of the four surrounding angels are just visible above and below the edge of the mandorla; their two coloured wings are spread wide. Each angel has a tania in his hair.

On the west wall above the Koimesis, on both sides of a window and just below the ceiling of the church there is a picture of the Pentecost.[69] On each side of the window two rows of six apostles are seated in a half-circle on throne-like chairs. There are no “cloven tongues like as of fire” on each of them to indicate that they have all been filled with the Holy Ghost, but instead they have been pictured gesticulating and talking to each other. At the top of the two rows Peter, on the left, and Paul, on the right, can be distinguished. The latter stretches his right hand in the direction of Peter.

The Assumption of the Virgin or Koimesis is usually depicted on the west wall of a church, but here the painters made an exception by starting the scene on the south side. Archangel Gabriel announces to the Virgin her future passing away. The story is extensively revealed in a Greek narrative, entitled: “The discourse of St. John the Divine concerning the Falling Asleep of the Holy Mother of God.”[70] It states: “When the all-holy glorious mother of God and ever-virgin Mary, according to her custom, went to the holy sepulchre of our Lord to burn incense, and bowed on her holy knees, she besought Christ our God who was born of her to come and abide with her.” Verse 3 continues: “Now on one day, which was Friday, the holy Mary came as usual to the sepulchre, and as she prayed the heavens were opened and the Archangel Gabriel came down to her and said, ‘Hail, you who bore Christ our God; your prayer has passed through the heavens to him who was born of you and has been accepted, and henceforth according to your petition you shall leave the world and come to the heavenly places to your Son, to the true life that has no successor.’ And when she heard that from the holy archangel she returned to Bethlehem the holy, having with her three virgins who ministered to her. And when she had rested a little, she sat up and said to the virgins, ‘Bring me a censer that I may pray.’ And they brought it as it was commanded them.” The wall painting shows the Virgin sitting on a throne-like chair with her feet on a cushion. She looks up at the archangel coming down from heaven (pict. XI 36). Unfortunately the paint of the angel has disappeared. At the other side of the scene the Virgin is shown standing with both hands open as a sign of receiving the message. On the right the Virgin is depicted again sitting on a throne-like chair surrounded by more than three women. The Coptic version of this story[71] tells that Salome and Joanna and the rest of the virgins lived with Maria. The Virgin, dressed in a red maphorion, talks to the women in front of her, telling them what she had heard from the archangel and she bids her women friends farewell (pict. XI 37). The women around her listen in astonishment; their hands and faces express sorrow and grief. They are all, except one, clad in a dress of the same grey-blue colour. The unframed scene continues on the right towards the depiction of the Koimesis proper, the two scenes being linked by one of the disciples who stands round the bier of the Virgin but has also turned back, one hand to his chin, to listen to what the Virgin is saying. The narrative continues by telling that the Virgin prayed to her Son that the Apostle Johannes and the rest of the apostles “both those who have already come to dwell with you and those who are in this present world, in whatever land they may be, by your holy commandment, that I may behold them and bless your name that is greatly extolled, for I have confidence that you hear your handmaid in everything.” Verse 12 ff: “And the Holy Ghost said to the apostles, ‘All of you together mount up upon clouds from the end of the world and gather at the same time at Bethlehem the holy because of the mother of our Lord Jesus Christ’. Peter came from Rome, Paul from Tiberia, Thomas out of the inmost Indies, James from Jerusalem. Andrew the brother of Peter, and Philip, Luke, and Simon the Canaanite, and Thaddeus, who had fallen asleep, were raised up by the Holy Ghost out of their sepulchres. The Holy Ghost said to them ‘Do not think that the resurrection has occurred. The reason why you have been raised from your graves is so that you may go to greet with honour and wonderful signs, the mother of your Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. For the day of her departure has arrived, and she is going to abide in heaven’. And Mark, who was still alive, came from Alexandria with the rest, as has been said, from their various countries.” The scene as painted is of enormous size and by its magnitude honours Our Lady the Most Glorious, the Bogorodica Periblebtos (pict. XI 38). The Virgin lies on a bier which is surrounded by the apostles, six on each side and three archbishops in multi-crossed chasubles.[72] Christ, resplendent in golden himation within a round white-shining mandorla, stands behind the bier and holds in His arms the soul of His mother, which has been depicted as a miniature version of the Virgin, clad in white garments with small wings like an angel and sitting with her arms crossed. To the left and right of Christ stand six angels, some of them with candles lit, as the heavenly court that honours the mother of God. He is also accompanied by innumerable multitudes of the heavenly host descending from the open gates of heaven, which are depicted in a hyperbola at the top of the wall painting. In the air clouds bring the apostles to the place where the Virgin is going to abide: to heaven. On one of the clouds on the right the Virgin together with an angel ascends heavenwards. This refers to another apocryphal story,[73] which tells that all the disciples arrived on clouds, except Thomas. Verse 17: “Thomas was suddenly brought to the Mount of Olives and saw the holy body being taken up, and cried out to Mary, ‘Make your servant glad by your mercy, for now you go to heaven’. And the girdle with which the Virgin had girt her body was thrown down to him; he took it and went to the valley of Josaphat. When he had greeted the apostles, Peter said, ‘You are always unbelieving, and so the Lord has not suffered you to be at His mother’s burial.’” Verse 20 continues: “Then Thomas told them how he had been saying mass in India (and he still had on his priestly vestments), and how he had been brought to the Mount of Olives and seen the ascension of Mary and she had given him her girdle; and he showed it. They all rejoiced and asked his pardon, and he blessed them and said ‘Behold how good and pleasant a thing it is, brethren, to dwell together in unity.’” On the wall painting Maria can be seen throwing down her girdle to Thomas. Out of the windows of cuboid houses, which have been depicted on both sides of the descending angels, three women with sorrowful faces are looking down at what is happening. It is supposed that they are the three virgins who ministered to the Virgin.

On the right, the scene continues showing how the apostles carry the bier with the body of Maria to the sepulchre (pict. XI 39). A link between the two scenes is formed by an angel raising his sword to punish Jephonias, who is the man in red behind the bier. The story is told in the continuation of the Greek narrative of St. John the Divine. Verse 46 runs as follows: “And behold, as they carried her, a certain Hebrew named Jephonias, mighty of body, ran forth and attacked the bed as the apostles carried it, and lo, an angel of the Lord with invisible power struck his two hands from off his shoulders with a sword of fire and left them hanging in the air beside the bed. And when this miracle came to pass, all the people of the Jews who beheld it cried out, ‘Verily he is true God who was born of you, Mary, mother of God, ever-virgin.’ And Jephonias himself, being commanded by Peter that the wonderful works of God might be shown, stood up behind the bed and cried, ‘Holy Mary, who bore Christ who is God, have mercy on me,’ And Peter turned and said to him, ‘In the name of him who was born of her hands which were taken from you shall be joined back on.’ And immediately at the word of Peter the hands that were hanging beside the bed of our lady went back and joined Jephonias; and he also believed and glorified Christ, the God, who was born of her.” After this miracle the apostles carried the bier and laid the body of Maria in a new tomb at Gethsemane. This scene has been depicted on the right of the Koimesis. The narrative of St. John the Divine tells in verse 48, that for three days the voices of invisible angels were heard glorifying Christ. “And when the third day was fulfilled the voices were no more heard, and thereafter we all perceived that her spotless and precious body was translated into paradise.”

In this church there is a fine, fairly well-preserved series of wall paintings which relate to the life of Maria, as described particularly in the Protevangelium of James.[74] This apocryphal book is the main source of information about the life of the Virgin and is of great importance to the history of art. Its influence on the development of doctrines of Mariology was immense.[75] Although Luke gives some information about Maria and her parents Joachim and Anna, the Protevangelium of James narrates the birth of the Virgin, her life in the temple, how Joseph took her in his house, the Annunciation, and their travel to Bethlehem to be taxed and the birth of Christ. Parts of the Protevangelium which corresponds to the scene depicted on the wall paintings of the church will be cited here.[76] It starts on the wall in the bema below the Last Supper and continues along the south and north sides of the naos on the second row from the bottom.

The first two scenes show Joachim and Anna offering in the temple and their return home. “Joachim was a very rich man and he brought his gifts to the Lord twofold. The day of the Lord drew near and the children of Israel were bringing their gifts, but Joachim was informed: ‘It is not lawful for you to offer your gifts, because you have begotten no offspring in Israel.’” When checking in the record-book of the twelve tribes of the people “he found that all the righteous had raised up offspring in Israel. And he remembered the patriarch Abraham to whom in his last days God gave a son, Isaac. And Joachim was very sad and did not show himself to his wife, but went into the wilderness; there he pitched his tent and fasted forty days and forty nights, saying to himself, ‘I shall not go down either for food or for drink until the Lord my God visits me; my prayer shall be food and drink.’ Anna in her turn was lamenting: ‘I will mourn my widowhood, and grieve for my childlessness.’(2.4) And Anna was very sad, but she took off her mourning garments, washed her head, put on her bridal garments, and about the ninth hour went into her garden to walk there. And she saw a laurel tree and sat down beneath it and implored the Lord saying, ‘O God of our fathers, bless me and heed my prayer, just as you blessed the womb of Sarah and gave her a son, Isaac.’(4.1) And behold an angel of the Lord appeared to her and said, ‘Anna, Anna, the Lord has heard your prayer. You shall conceive and bear and your offspring shall be spoken of in the whole world.’ And Anna said, ‘As the Lord my God lives, if I bear a child, whether male or female, I will bring it as a gift to the Lord my God, and it shall serve him all the days of its life.’” The wall painting (pict. XI 40) shows a slender, youthful looking Anna dressed in a red maphorion standing before a gate with a tied up curtain symbolising her house, her hands open towards a small angel who announces the message to her. In front of her a tree and a well indicate the garden where she was walking. (4.2) “And behold there came two angels, who said to her ‘Behold, Joachim your husband is coming with his flocks for an angel of the Lord God has come down to him and said to him ‘Joachim, Joachim, the Lord God has heard your prayer. Go down from here; behold, your wife Anna shall conceive.’ (4.4) And, behold, Joachim came with his flocks, and Anna stood at the gate and saw Joachim coming and ran immediately and threw her arms around his neck saying ‘Now I know that Lord God has greatly blessed me; for behold the widow is no longer a widow, and I, who was childless, shall conceive.’ And Joachim rested the first day in his house.” The wall painting shows the embrace of the two before a gate (pict. XI 40). (5.2) “And her months were fulfilled; in the ninth month Anna gave birth. And she said to the midwife ‘What have I brought forth?’ And she said ‘A female.’ And Anna said ‘My soul is magnified this day.’ And she lay down. And when the days were completed, Anna purified herself and gave suck to the child, and called her Maria.” A rather extensive scene (pict. XI 41) shows Anna sitting on a bed, the suckling lies in a cradle near to her, already dressed in the way she will always be depicted. A young girl sits near the cradle on the ground and is busy spinning wool. In the background two maidens bring Anna food and another is busy fanning her.

The series continues with a very rare painting: Joachim and Anna, seated on a bench are cuddling the child (pict. XI 42). (6.1) “Day by day the child grew strong; when she was six months old her mother stood her on the ground to see if she could stand. And she walked seven steps and came to her bosom. And she took her up saying ‘As the Lord my God lives, you shall walk no more upon this earth until I bring you into the temple of the Lord.’” The wall painting shows the child dressed in a purple maphorion. She reaches out her hands to her mother Anna, who sits on a throne-like chair. Her hands are ready to hold the child should she fall (pict. XI 43). Behind Maria, a maid carefully guides her. (6.2) “On the child’s first birthday Joachim made a great feast, and invited the chief priests and the priests and the scribes and the elders and all the people of Israel. And Joachim brought the child to the priests, and they blessed her saying ‘O God of our fathers, bless this child and give her a name eternally renowned among all generations.’” Apparently the painters did not know the true story for they mistakenly painted the seven steps of the child first, followed by the feast. The latter painting resembles the Hypapante of Christ: Joachim with the child in his arms and followed by Anna presents the child to three priests who bless her as they sit behind a table laid with food and cups (pict. XI 44). (7.1 ff) “The months passed and the child grew. When she was two years old Joachim said ‘Let us take her up to the temple of the Lord, so that we may fulfil the promise which we made, lest the Lord send some evil to us and our gift be unacceptable.’ And Anna replied ‘Let us wait until the third year, that the child may then no more long for her father and mother.’ And Joachim said ‘Let us wait.’ And when the child was three years old Joachim said ‘Call the undefiled daughters of the Hebrews, and let each one take a torch, and let these be burning, in order that the child may not turn back and her heart be tempted away from the temple of the Lord.’ And they did so until they had gone up to the temple of the Lord. And the priest took her and kissed her and blessed her, saying ‘The Lord has magnified your name among all generations; because of you the Lord at the end of the days will reveal his redemption to the sons of Israel’. And he placed her on the third step of the altar, and the Lord God put grace upon her and she danced with her feet, and the whole house of Israel loved her. (8.1 b) And Mary was in the temple of the Lord nurtured like a dove and received food from the hand of an angel.” The slightly calcined wall painting follows the story revealed in the Protevangelium: at the left side Joachim and Anna are looking at how the child is greeted by a priest, who blesses her on the forehead with his right hand while his other hand is raised in a gesture of welcome. The child stretches her hands towards the priest (pict. XI 45). She wears a white embroidered head-shawl that falls down on her back over a dark red maphorion, under which is a blue skirt. Between her parents and Maria six maidens are waiting and looking with gesticulating arms to what is happening. In the right upper corner of the wall painting with her feet ‘on the third step of the altar’ sits the little child on a throne-like chair while an angel brings food to her. In this way Maria was brought up in the temple until she was twelve years old. The Protevangelium of James continues: (8.2 ff) “When she was twelve years old, there took place a council of the priests saying ‘Behold, Mary has become twelve years old in the temple of the Lord. What then shall we do with her lest she defiles the temple of the Lord?’ And they said to the high priest ‘You stand at the altar of the Lord; enter the sanctuary and pray concerning her, and that which the Lord shall reveal to you we will indeed do.’ And the high priest took the vestment with the twelve bells and went into the Holy of the Holies and prayed concerning her. And behold, an angel of the Lord appeared and said to him ‘Zacharias, Zacharias, go out and assemble the widowers of the people, and to whomsoever the Lord shall give a sign she shall be a wife.’ And the heralds went forth through all the country round about Judaea; the trumpet of the Lord sounded, and all came running.” The painters have combined these events into one scene. The wall painting depicts the high priest kneeling in prayer. Before him are the closed doors of a walled area in which stands a ciborium on four pillars; behind the door rods can be seen. Beside the ciborium stands Maria looking upwards (pict. XI 46). (9.1) “And Joseph threw down his adze and went out to their meeting. And when they were gathered together, they took the rods and went to the high priest. He took the rods from them all, entered the temple, and prayed. When he had finished the prayer he took the rods, went out and gave them to them; but there was no sign on them. Joseph received the last rod, and behold a dove came out of the rod and flew on Joseph’s head. And the priest said to Joseph ‘You have been chosen by lot to receive the virgin of the Lord as your ward.’ But Joseph answered him ‘I have sons and am old; she is but a girl. I object lest I should become a laughing-stock to the sons of Israel.’ And the priest said to Joseph ‘Fear the Lord your God and remember what God did to Dathan, Abiram and Korah,[77] how the earth was split in two and they were all swallowed up because of their rebellion. And now beware, Joseph, lest these things happen in your house too.’ And Joseph was afraid and received her as his ward. And Joseph said to Mary ‘I have received you from the temple of the Lord, and now I leave you in my house and go away to build my buildings. I will return to you; the Lord will guard you.’”

The wall painting shows the high priest on the left with Joseph opposite him (pict. XI 47). The high priest holds a rod in his right hand which he is intending to hand over to Joseph. Just behind is Maria, a flame burns exactly above her head.[78] Joseph holds his hands as if discussing the question over the head of Maria, but it can also be explained that he is receiving her. She stands between them, shown as rather small to indicate that she was only a young twelve year old girl. Behind Joseph a large number of old men stand there listening and discussing among themselves. It is remarkable that none of them have rods.

The next scene is the Annunciation to Maria by an angel (pict. XI 48). She is supported by two women servants. She looks up somewhat amazed at a small flying angel above her who is announcing the message of the Lord to her (11.1 ff). “And (Maria) took the pitcher and went out to draw water, and behold, a voice said ‘Hail, highly favoured one, the Lord is with you, you are blessed among women.’ And she looked around to the right and to the left to see where this voice came from. And, trembling, she went to her house and took the purple and set down on her seat and drew out the thread. And behold, an angel of the Lord stood before her and said ‘Do not fear, Mary; for you have found grace before the Lord of all things and shall conceive by his Word.’ When she heard this she considered it and said ‘Shall I conceive by the Lord, the living God, and bear as every woman bears?’ And the angel of the Lord said ‘Not so, Mary; for the power of the Lord shall overshadow you; wherefore that holy one who is born of you shall be called the Son of the Most High. And you shall call his name Jesus; for he shall save his people from their sins.’ And Mary said ‘Behold, (I am) the handmaid of the Lord before him: be it to me according to your word.’” The wall painting illustrates a well outside a house where a maiden is busy turning a wooden wheel to get the pitcher up (pict. XI 49).

Six months later Joseph came home from his buildings and noticed that Maria was pregnant (pict. XI 49, right side). He was wondering who had betrayed him and defiled her, remarking to himself that he received her as a virgin out of the temple and did not protect her. He reproached her, saying (13.2 b) “‘You who are cared by God, why have you done this and forgotten the Lord your God? Why have you humiliated your soul, you who were brought up in the Holy of Holies and received food from the hand of an angel?’ But she wept bitterly, saying ‘I am pure, and know not a man.’” Joseph was desperately wondering what to do with her and feared greatly being opposed to the law of the Lord. But at night an angel appeared to him in a dream and informed him that what was in her was of the Holy Spirit. The Protevangelium continues by telling that Annas the scribe came to the house of Joseph and saw that Maria was pregnant. Whereupon he went to the priests to inform them that Joseph had secretly consummated his marriage without disclosing it to the children of Israel. Joseph and Maria are questioned and deny every responsibility. They have to undergo the divine judgement by drinking the water of the conviction of the Lord in order to make their sins manifest in the eyes of the priests (pict. XI 50). They are sent into the hill-side and return without being harmed (16.2 b). “And all the people marvelled, because sin did not appear in them. And the priest said ‘If the Lord God has not revealed your sins, neither do I judge you.’ And he released them. And Joseph took Mary and departed to his house, rejoicing the God of Israel.” The somewhat vague wall painting shows Joseph and Maria and a priest. Maria is drinking the water of conviction while Joseph angrily looks on with one hand to his chin.

The last painting of this cycle shows Joseph asleep on a mattress and the angel of his dream, telling to him that Maria’s pregnancy is caused by the power of the Lord (pict. XI 51).

Since both the diaconicon and the prothesis are relatively small rooms it is rather difficult to take pictures of the side walls. The half cupola of the diaconicon contains an impressive John the Baptist (pict. XI 52).[79] With a grave face he looks at the viewer and with his right hand he points at himself. He holds a scroll in his left hand and a staff with a small cross on top under his left arm. The painters have depicted him with dishevelled hair and beard. Below him the busts of Hypatios and another, unknown, bishop have been depicted and below them there is a painting of Bishop Ignatios Theophoros.[80] Inside the small room the walls are covered with paintings relating to the life of John: the announcement to Zacharias in the temple; the meeting of Maria and Elisabeth; the birth of the saint and Elisabeth who is accepting presents from three women; the bathing of the child and the name-giving by his father who writes his name on a writing table. A very different painting in the same small room is the depiction of the three young men in the fiery furnace.

On the other side, in the half-cupola of the prothesis, Maria has been painted holding the Christ-child to her breast, a so-called Maria Znamenie (pict. XI 53). The child is surrounded by a round white medallion. It looks as though he is sitting in it. Also here a stern-faced Maria looks at the viewer. The Christ-child has a nimbus with a jewelled cross. He holds a scroll in his left hand, but does not make a gesture of blessing. Below her the busts of two bishops have been painted. The one on the left is probably Bishop Anthimos with a brown beard and the other with a grey beard is Bishop Parthenios. Below them there is an unknown bishop.[81]

On the second row of the south side wall of the prothesis, can be found a remarkable wall painting (see fig.) with the infrequently painted Vision of Peter of Alexandria.[82] Peter was bishop of Alexandria shortly before Bishop Arius began preaching the heretical doctrine of monophysitism and the Vision usually relates to his condemnation of the teaching of Arius. The wall painting shows Peter standing before the altar on which the Gospel lies. Next to the altar stands an adolescent Christ dressed in only a veil, pointing to the Gospel. The painting resembles the style of ancient figures. Before the altar lies the heresiarch Arius in proskynese. The earliest known version of the Vision is in the Church Santa Maria Antiqua at Rome dating about 757-767. The scene that has been painted in this church is one of the first paintings of this kind made in Macedonia.

Figure from Grozdanov, Etudes sur la peinture d’Ohrid, Skopje, 1990, p. 106

The lowest row inside the naos of the church as well as the columns supporting the cupola, contain portraits of a large number of saints. On the south wall a most remarkable and unique depiction has been painted of Peter bearing a church on his shoulders.[83] Regrettably, the painting is out of sight since, unaccountably, the church authorities have placed in front of it a large immovable cupboard containing informational material, which could easily have been placed in the almost empty exo-narthex. The painting shows Peter carrying a church on his back.[84] The front of the church shows a seraphim with six wings. Peter stands on the prostrate figure of Hades, accompanied by an angel, who pierces the body of Hades with a lance at the upper side. Christ has extended a hand towards Peter. An epigraph on the wall reveals the words: “And I say also unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”[85] The composition appears for the first time.[86] We can only guess as to why Michael and Eutychius rendered this unusual wall painting and whose instructions they followed. There is no other example known in the orthodox world. Immediately next to Peter, the Apostle Andrew has been pictured as an old man with grey hair.[87] Andrew and his younger brother Simon Peter were the first of Christ’s disciples. In his left hand Andrew holds a scroll and a long staff with a small cross at the end like a sceptre.[88] The picture of Peter standing on the prostrate figure of Hades has a doctrinal rather than a historical significance.[89] The scene is undoubtedly intended to show the ultimate triumph of the Church over the evil that originates from Hades and Satan.

Around the neck of Peter hangs a bunch of three keys, in accordance with Christ’s words to him: “And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven; and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth that be loosed in heaven”.[90]

The portrayal of Peter on one side together with his brother Andrew may have a special meaning since a legend reveals that Andrew was the founder of the church at Byzantium. It is therefore significant that he has been placed just opposite the wall painting of Kliment, the founder of the church in Ohrid. Another story tells how Andrew travelled and preached in Macedonia.[91]

Next to this scene there is the door leading to the exo-narthex and the south chapel. Above the wooden beam of a door the busts of three saints have been depicted in one frame. They are from left to right Akakios, Kyrikos and the woman saint Julitta (pict. XI 54). Acacius[92] was a captain in the imperial army of Cappadocia, who was tortured during the persecutions under Emperor Diocletian. He has been pictured here as a young man with a beardless face and long brown hair. Julitta and Kyrikos[93] are usually depicted together as mother and child. Julitta came from Iconium and on her flight she was captured in Tarsus. Julitta was beaten with a throng while her son was forced to watch. The desperate child attacked Governor Alexander and scratched his cheek. The Governor became very angry and threw the three year old Kyrikos down the steps of the palace,[94] fracturing his skull and killing him. Because Julitta, in spite of severe tortures, refused to renounce her belief, she was crucified and afterwards beheaded. The wall painting depicts the young boy in the middle, but not as a child, with short brown hair. His mother Julitta is on the right; she has a young face and her head is covered by a red maphorion.

To the left of this scene the standing figure of Monk Antonius has been painted[95] (pict. XI 55). Antonius, a highly revered saint, is considered to be the patriarch of all monks. Antonius has been depicted as an old man with a short beard divided into two points. His head is covered with a cape forming part of his hairy monk’s habit. He holds an unrolled scroll in his left hand.

Next to him stand two other monks, Euthymius and Arsenius.[96] Euthymius has been depicted as an old man with a long beard reaching down to his thighs. He also holds an unrolled scroll in his hand (pict XI 61). Euthymius was born at Melitene in Armenia in 378. At the age of twenty he went into a monastery near Jerusalem; later he went to Jericho and further into the desert where he established several monasteries (lavras). He died in 473. He is considered to be one of the great fathers of monastic life. Arsenius, painted on the right in this scene, also lived in the desert, where he died at the age of 90 years old in about 449 in the area of Memphis. He was a Roman deacon who was summoned to Constantinople by Emperor Theodosius the Great to become the tutor of his sons Arcadius and Honorius. After ten years he abandoned the court and retired to the desert of Egypt to live as a hermit, weeping over the feebleness of Arcadius and the foolishness of Honorius.

On the left of the door leading to the narthex two saints have been depicted who have been identified as Chariton and Stephan the Younger (pict. XI 56) [97] Chariton has been depicted as an old man with a bald head and a white beard; he wears a monk’s habit. He probably lived in the desert near Jericho where he died in about 350.

Stephan the Younger lived in the famous Auxentius Monastery in Bithynien, where he became the abbot. He refused to accept Iconoclasm and it is said that for that reason he was murdered without trial in 764. He is usually depicted holding an icon in his hand.

Most paintings of saints painted on the north wall are in very bad condition, except for the two saints at the left side of a door. One is an unknown monk, but the other is a well-preserved figure of Bishop Nicholas (pict. XI 57). He has been depicted full length in bishop’s vestments and only three poloi on his omophorion. He makes a gesture of blessing and holds an open evangelarium in his left hand. The painters have succeeded in giving his face a serene but stern expression.

On the other side of the door two other bishops have been painted, who have historical associations with this church (pict. XI 58). On the left is Kliment and on the right is Bishop Kavasilas of Ohrid. Kliment has been depicted with a long grey beard. He is dressed in a phelonion with an omophorion around his shoulders decorated with large crosses. Under the phelonion a decorated epitrachelion and an encheirion, decorated with the face of a saint can be seen. He has an impressive, grave face. His right hand makes a gesture of blessing and in his other hand he holds a richly decorated evangelium. Bishop Kavasilas wears an omophorion over a polystaurion at the sides embroidered in gold. He also holds a decorated evangelium in both hands.