Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

Byzantine Art

In the beginning Christianity developed slowly. In fact all the present day facets had to be evolved, from the Gospels to the liturgy. The early Christians had no need for special building for worship and, for at least a century and a half, were content with the “house-churches” to which there are several references in the New Testament and in the second century.[1] The most important part of the religion was the Eucharist, which was usually celebrated in a room in a private house. Sometimes the place where the people worshipped took on a more permanent character and was called the ecclesia. Jewish melodic recitation may have influenced the mode of chanting the Christian service.[2] There is nothing whatever to suggest that before the reign of Constantine the Great the church had made any attempt to develop a monumental architecture of its own.[3] The situation changed favourably during and after the reign of Constantine the Great. At his instigation building activity started in Constantinople, Rome, Alexandria, Antioch and many other places. Jerusalem, after having been sacked by the Romans, became less important, but the place where Christ had suffered on the cross, and where his body was laid in a sepulchre, could not be forgotten. Consequently, Constantine ordered the construction of the churches of the Holy Sepulchre and of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem and the Nativity Church in Bethlehem. Most of the new churches had a basilica form.

After the initiatives of Constantine early Christianity spread rapidly over large areas of the Roman Empire. It came to the towns that already existed in Macedonia at that time which were known by their old names, like Stobi, Lychnidos, Heraclea Lyncestis, Scupi and others.[4] Ancient cities in Macedonia developed into significant centres of early Christianity, where basilicas and other episcopal centres were erected, or existing edifices were re-used for Christian worship.

An important role was played by the archbishopric Prima Justiniana, which was organised by Emperor Justinian I in 535 - 545. The establishment of the political and ecclesiastical centre Prima Justiniana in the ancient town of Scupi laid the foundations of an independent church organisation in the regions of Eastern Illyricum and Macedonia. It also formed the basis for the further independent development of the church in Macedonia and the whole of the Balkan Peninsula. The first independent church organisation of the Slavs was established exactly in these territories.[5]

Stobi was in turn a Hellenistic, Roman and early Byzantine city. In Roman times it was the largest city of northern Macedonia.[6] Its location about 26 km south of present day Veles at the juncture of two important rivers, the Erigon and the Axius, today known as Crna reka and Vardar, was well chosen to feed its population because it had fertile soil and sufficient water.[7] Its existence is mentioned in sources of ancient times. It was of great military and commercial importance. When in 386 AD it became the capital of the Roman province Macedonia Salutaris the city prospered in welfare and appearance. Soon after the beginning of Christendom the city had its own bishop. The earliest name known is that of Bishop Budios who attended the Nicene Council in 325. Bishop Nicholas is reported to have attended the Chalcedon Council of 451. Between 473 and 483 the city suffered due to a conflict with the Ostrogoths who plundered it in 479 and partly destroyed it. Bishop Philippos ordered the construction of a large new basilica in about the year 500. This was confirmed by the discovery of an inscription to that effect on a portal between the narthex and the naos of the church. A large part of the city of Stobi was destroyed by the same severe earthquake that also destroyed Skupi in 518.

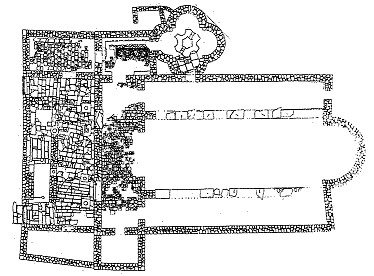

Archaeological excavations have brought to light a large number of secular and ecclesiastical buildings in Stobi: Roman palaces, an amphitheatre, basilicas, an aqueduct and even a sewerage system (pict. VI 1). Most of the buildings discovered in this late Roman city originated in the fourth and fifth century. A relatively large number of important buildings, including a number of basilicas such as the Episcopal Basilica and the so-called North Basilica with a baptistery (fig. 1) had mosaic floors.

Fig. 1 Plan of the North Basilica at Stobi

So too did the “Synagogue” Basilica, mentioned by this name because originally it was an old synagogue that in the fourth century was converted into a Christian temple (pict. VI 2). On one of the walls graffiti has been found in the shape of a menorah. Another example is the Palace of Polyharmos. In the area of the Amphitheatre, the bishop’s palace was found close to the previously mentioned large basilica or Episcopal Basilica. The town was surrounded by thick walls with two gates.

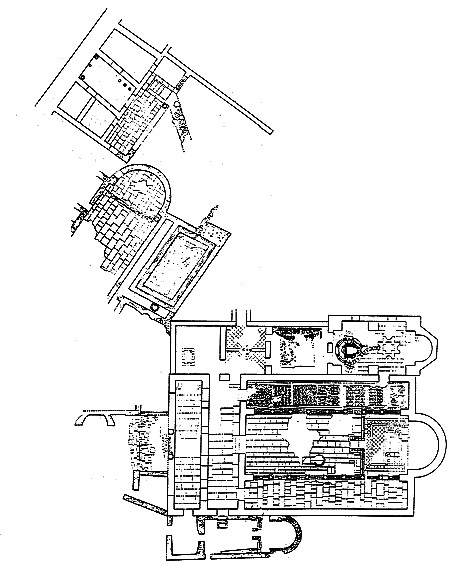

During excavations between 1970 and 1975 archaeologists uncovered about four metres below the Episcopal Basilica an older Christian basilica with three naves containing mosaics with geometrical motives[8] (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Old Episcopal Basilica at Stobi

Below the mosaic floor a coin was found, which was in use during the period 360 to 370. This gives an indication of the date of construction. Other archaeological evidence suggests that the basilica was built some time after 350 A.D., making it one of the earliest well-preserved churches in the Balkan Peninsula with some of the oldest floor mosaics of Macedonia. The mosaic floor contains the abbreviation X and Y for Jesus Christus.

In the floor two texts can be distinguished, one within a rectangle with grapes and ornaments, the other one made in a square within a circle. The first contains a Greek text which reads in English: “The holy church of God has been renovated during the time of his holiness Bishop Eustathios”. This gives a more precise indication of its date, for Eustathios was bishop from about 343 to 381. There are, however, no indications found of a “renovation”. It is possible that there was an older church on the same spot if we bear in mind that Bishop Budios attended the Nicene Council in 325. The other mosaic contains the Greek text reading in English: “Prayers and alms, giving and fasting and repentance from a pure heart, save from death”.

It can be concluded from the excavations that the church was extended in an easterly direction at a later period. Attached to the older church, was a Baptisterium located at the southern side and dating from the end of the fourth century. It was built in quatrefoil and in the centre was the piscine for baptism (pict. VI 3). The floor of the baptistery is covered with beautiful mosaics made of white and black tesserae bearing an ornamental decorative pattern with birds and deer (pict. VI 4 and 5).

Inside this baptistery excavators found fragments of wall paintings, from which the conservators, with diligence and meticulousness, have reconstructed the complete composition, which was originally painted in one of the four niches.

“In the centre of the composition a semicircular niche is shown, containing the figure of a young saint, whose body is en face, but whose head is turned to the right. The figure is visible above the waist, revealing that it is clothed in a pale blue chiton with a bright ochre cloak thrown over the left shoulder. He holds a finely carved and richly ornamented wooden box, the corners of which are held together by three decorative metal staples. The sides of the box are decorated with dark grey triangles meeting at their points in imitation of encrustation. To the right of the central figure, five saints in a row can be distinguished: a middle aged saint with a short beard, a moustache and hair which covers part of his forehead. He is facing the central figure and has raised his right hand. Next to him is a somewhat younger saint who can hardly be made out due to damage to the face, and three others, two of them clean shaven. Part of their clothing has been preserved and shows that it resembles that of the other saint. Around the head of the central figure, a skilful shading of the background produces a brighter circular segment which is not outlined. This does not appear around the heads of the other saints. It can be concluded that the central figure wears a halo. In the background, above the drawn niche, are decorative curtains in two colours, raw and burnt ochre. At the top, on the curtains, the signature (H)ERM[O]LAOS - in Greek letters - appears in two parts, forming a semicircle. The first part of the signature (H)ERM[O], consists of five letters, of which three and a part of the fourth are visible. They are written in very dark burnt ochre on a grey ochre background (the colour of the curtains). The second part of the much more readable signature, LAOS, of four letters, is written in white on a curtain of burnt ochre. Thus the entire signature reads HERMOLAOS. The deciphering of the oldest fresco so far discovered in the Republic of Macedonia has been made much easier by the discovery of the first part of the signature and by the central figure holding a large ‘wooden’ box in his hand” [9].

It is known that such boxes are held by saints known for their healing powers, such as Panteleimon, Kuzman (Cosmas) Damjan (Damian) and others. There are many examples of this in medieval frescoes. The holy martyr Hermolaos is one of the Nicomedian[10] priests, who, in the time of the Roman Emperor Maximian,[11] was condemned to be burnt in the church along with 2,000 other Christians in which they had taken refuge from their persecutors. Hermolaos, however, together with two other priests, Hermippus and Hermocrates managed to escape death. This is recorded in his hagiography (his day is celebrated on the 26th of July). The martyrdom of the 2,000 Christians burnt in the church is celebrated on the 28th of December.

At this time, the saint and martyr Panteleimon was also living in Nicomedia, practising medicine. According to his hagiography his father Evstorij (Eustorius) was a pagan, but his mother Evula was a Christian. Panteleimon was summoned by Hermolaos, was taught the Christian faith and was baptised. Later, after Panteleimon had become renowned for several miracles of healing, he, Hermolaos, Hermippus and Hermocrates were condemned to death and executed together on the 27th of July 304 AD.

These saints are mentioned in the prayers which accompany the blessing of the holy water and the baptism, and therefore their presence of their images in the Baptistery is, theologically, quite logical. The frescoes have been dated to the end of the fourth century or the beginning of the fifth.

It is remarkable that Hermolaos has been illustrated as a relatively young man with a pointed beard, because literature generally refers to him as an old priest. He belonged to the so-called Anargyroi, physicians who healed without asking for money.[12]

Heraclea Lyncestis – close to the present town of Bitola in the Republic of Macedonia - is said to have been founded by Philip II of Macedonia, in about the year 350 BC. The fertile surroundings brought prosperity to the town, which later became a prominent community alongside the Via Egnatia after it fell under Roman rule in 168 BC. It flourished as a Roman city. When Christianity was spreading to this region Heraclea became a bishopric. Bishops from here attended among others the Councils of Nicaea in 325 and Chalcedon in 451.

The old town has been partly excavated (pict. VI 6). Besides Greek and Roman finds, a number of secular and religious buildings have been found, among them a small episcopal basilica (pict. VI 7), a large basilica with aisles and the episcopal residence. The floor of the small basilica was covered with a mosaic laid down in the opus sectile technique, whereas the apse had a brick floor with tiles. A low marble iconostasis separates the sanctuary from the church. The small basilica is thought to have been in use from the end of the fourth to the end of the sixth century. It underwent a number of reconstructions. The outer narthex had a fine mosaic floor dating from the fifth century.

Fig. 3 Mosaic narthex large basilica Heraclea Lycestis The large basilica had monumental proportions: it contained a nave with a semi-circular apse at its eastern end and two aisles. At the end of the aisles were a diaconicon and a prothesis; the narthex was on the western side. The floor of the narthex is covered with a mosaic of good quality laid down in the opus tesselatum technique with geometric, floral and animal motifs, made by skilful artists, surrounded by a complicated meander border with octagonal forms with sea animals or birds included (fig. 3). It is of the finest artistic quality. The spiral interlacings contain geometrically-patterned borders of squares and hexagons and inside the border is a line of ten trees of different species, some bearing fruit, placed on either side of the central composition. Under the trees are smaller plants, including roses. An amphora in the centre is surrounded by a deer and a hind; two peacocks are facing each other at the upper side. Wine-tendrils bearing grapes also surround the amphora. Between the trees a number of animals can be seen: a goat, a hunting lion, a bull and a deer (pict. VI 8, 9 and 10). Of interest is a dog tied up to a tree. An attempt has been made to give a Christian interpretation to these mosaics. Thus the dog Cerberus, the guard of the Hades, has become according to this interpretation the protector of Paradise.[13] |

A somewhat more exaggerated interpretation is that the depiction in the mosaics of an amphora flanked by pairs of stags and birds should be understood as the Earthly Paradise. It seems difficult to explain a lion attacking a bull, or a leopard tearing apart a dead deer as a form of Christian salvation. There is little to indicate that the trees and their associated creatures were intended in any more than their literal sense; that is, they illustrated terrestrial nature red in tooth and claw and in all its changeability.[14] The composition represents the earth surrounded by a border of water creatures. The central composition (with the amphora) cannot be a literal portrayal of the Garden of Eden, for the motifs enclosed within the wreath fit neither the biblical nor the patristic descriptions of the Earthy Paradise, which was furnished with a variety of fruit trees and with the four rivers, which flowed from a single river, or from a fountain.[15] In the mosaic at Heraclea, however, the central composition does not enclose fruit trees, but only a vine and smaller plants, nor are streams or rivers to be seen. It is therefore difficult to read these motifs as a portrayal of the Earthy Paradise in its literal sense.[16]

The border of the mosaic, composed of 36 octagonal fields, can also be seen in other Roman mosaics. They do not bear any inscriptions.

These kinds of mosaics – not having any directly specific Christian meaning - were well-known in the Roman Empire. It might be assumed that these buildings were founded before Christianity became the religion of the city and that new buildings were either rebuilt on the same spot or re-used for Christian purposes.

In the fifth century the town was plundered by the Ostrogoths.

Lychnidos,[17] located on the hill above present Ohrid, was the centre of an Illyrian tribe in the fourth century BC. It is not known when it was founded, but it was already mentioned in old Roman records. An ancient legend tells that Cadmus, King of Thebe, when he was banished from his homeland, fled to the shores of the lake and founded Lychnidos.[18] The town was conquered by the Romans in 148 BC. When the Romans built the Via Egnatia, Lychnidos was one of the places along it. Excavations proved that it was already a town of importance by the discovery of its own minted coins from the second century. These coins had a characteristic design of a Macedonian shield with a star in the middle on one side and on the other a ship with an ornamental prow and the Greek inscription “Lychnidion”.

The first Christian missionary who is said to have come to Lychnidos was Erasmo of Antioch. By the third century some early Christian churches probably already existed there. On the hill, in the area now called Plaosnik above the present town of Ohrid, one can find the remnants of an old Christian basilica, most probably built in the fifth century, when Lychnidos became an important episcopacy. It was built partly of stone blocks reused from Greek/Roman buildings and partly of brick. The walls have been preserved up to a height of about one metre. The floor of the church contains mosaics from the same period with figurative plant, flower and animal motifs. About one hundred square metres of these mosaics have been preserved. The church had three apses, a narthex, an atrium and a baptistery. Most probably this church was the seat of the Bishop of Lychnidos. It is generally accepted that the walls of this church were covered with mosaics as well. The basilica collapsed after a severe earthquake in the sixth century. Just beside this sanctuary one can see the foundations of a trefoil building built on the foundations of an older building and the foundations of a single nave church.

A hundred metres lower down the hill Clement built his Sveti Panteleimon Church. After his death the saint was buried inside the church in a sarcophagus which he designed himself. Some centuries later the Turks built the Imaret mosque over the ruins of this old church. The remains of the saint were disinterred before the building of the mosque and were taken to a small church bearing the name Old Sveti Clement’s Church. His relics were later placed in the church Sveti Bogorodica Peribleptos, which became better known under the name Sveti Kliment.

In 2001/2002 new excavations started. It was expected that remnants of the old town would be found on the hill and this was confirmed. The trees and about one metre of earth and stones were removed and the Imaret Mosque was dismantled. It was discovered that Clement built his church partly on the walls of an underlying Roman basilica. Roman houses were discovered with some column feet (torus). Of interest is the discovery of an early Christian baptistery with a floor covered with mosaics, located east of the Roman basilica, having about the same form as the one found in Stobi. The piscine was covered inside with marble slabs; some steps led down to the water.

Most probably remnants of Clement’s old university were discovered as well. The space between the fifth century Christian basilica and Clement’s Sveti Panteleimon was used between the eighth and the thirteenth century as a cemetery. A large number of graves from these periods were discovered; the bones were removed for reburial after having been studied.[19]

The old walls surrounding the town have recently been renewed and partly rebuilt. It may be assumed that they too originate from Roman times, or perhaps are even older.

On the site of the Roman basilica, where Clement built his church and the Turks a mosque, a completely new church has been erected, built in a fantasy style that attempts to re-create the appearance of an old Christian church (pict. VI 11). It is questionable whether at the present time it is archaeologically justified to build a new edifice on old foundations, but the new parts of the walls are at least separated from the old by a thick layer of lead sheeting. The new walls of the church have been built on these sheets. The church was consecrated on August 11, 2002. A special ceremony was held for the reburying of the saint’s remains in a special sarcophagus.

Scupi is the old Illyrian name of present day Skopje.[20] It came under the sway of the Roman Empire at a rather late date, somewhere during the time of Emperor Augustus. Veterans of the Roman seventh legion settled here, which had an impact on the ethnic Illyrian population. In 346 AD a bishop of Scupi is already mentioned, which proves that Christianity had penetrated here at an early date. A large earthquake, most probably in the year 518, destroyed everything in old Scupi, including the basilica, other churches and the bishop’s residence. The old town was never rebuilt. The population that survived fled to the mountains. Only a number of years later during the reign of Emperor Justinian I (527-565), a new town was built on the banks of the River Vardar, about five kilometres from the ruined town, which is now known under the name Skopje.

Not far from the monastery at Zrze, about 30 kilometres from Prilep, an early Christian basilica has been found dating from the fifth-sixth century, about which no information is available.

A large episcopal basilica was excavated at Bargala,[21] about 10 kilometres north-east of Štip. This work took place during the years 1966-1969, on a site known as Goren Kozjak. Although completely unknown today Bargala was an important centre in the valley of the Bregalnica River. The town was surrounded by a fortified wall. The basilica was built about the end of the fourth century and most probably remodelled in the fifth-sixth century. It contained a naos and two naves, an apse, a narthex and an exo-narthex, while at the northern side a baptistery was added (fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Bargala, Episocpal Basilica, M. Milojević

From an inscription on an impost block in the west facade it may be conjectured that the church was founded by Bishop Hermias. Another name from the past is that of Bishop Dardanius, who attended the Council of Chalcedon.[22] From the discovery of tesserae in the apse it may be concluded that part of the apse and the triumphal arch were covered with mosaics. It is believed that the town was attacked and destroyed in about the year 585.[23]

Fig. 5 Church Martyrium at Konjuh

Other old churches which have been excavated in other places include a martyrium church at Konjuh near Kumanovo.[24] Its foundations at Konjuh are remarkable (fig. 5) because of their rhomboidal form. The inside of the naos has the shape of a horseshoe, closed at the east end. On top was a large dome, which is evidenced by the foundations of the pillars. It is assumed that the altar contained relics of a martyr. The narthex with an entrance in the western wall consisted of three parts. The remnants are in very bad state, and almost completely ruined.

In addition to for the towns mentioned so far, other locations with Christian basilicas have been discovered and excavated. It may be supposed that each basilica served the people within its area but hardly anything is known of the circumstances or the relevant environment.

An early Christian basilica has been found near the village Radolišta, a small town in the vicinity of Struga. It was a basilica with two aisles and a large semi-circular apse. The floor was decorated with mosaics, a small part of which has survived. On the basis of these mosaics the basilica has been dated as fifth or early sixth century. The mosaics are not on view.

In the same district of Struga, in the village Oktisi located about 10 kilometres north, another old Christian basilica was discovered in 1927. This one had a narthex and a sacristy. In the narthex, mosaics were found which could be dated to the late fifth or beginning of the sixth century. These mosaics are covered with sand and are hidden from view.

In the vicinity of the village Vraništa, some five kilometres north of Struga, another large basilica has been discovered from a somewhat later period. Parts of the surviving walls are up to four metres high. The rest the building is in a ruined state and no decorations have survived. Moreover, there are no written records from which any information can be gathered about the construction. On the basis of its architectural features it is assumed that this basilica dates from the tenth or eleventh century.

The Basilica of the Fifteen Holy Martyrs of Tiberiopolis - bazilikata Sveti Petnaeset tiberiopolski mačenici - near Strumica was excavated in 1973. The basilica was built in two stages: the first in the fourth and fifth centuries, the second in the seventh century when the relics of the martyrs were brought here (fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Basilica of XV Tiberiopolis Martyr, Strumica. V Liličić

A small wall painting discovered in a necropolis at the site of the Fifteen Martyr-Saints of Tiberiopolis,[25] has been dated by researchers as belonging to the end of the ninth or beginning of the tenth century. Who the martyrs were is not exactly known. It is said that they perished during persecutions in the short reign of the Roman Emperor Julianus Apostata (361-363), whose study of neo-Platonism turned him against Christianity. That they were martyred is remarkable, because Constantine the Great had already confirmed the Edict of Toleration in 313, allowing Christians to practise their religion. Theophylact, the Archbishop of Ohrid,[26] (ca 1088-ca 1110) tells about seven hundred years later, most probably on the basis of older sources, that the martyrs were buried in the Strumica public cemetery, where a church and a sepulchre were later erected. This could be proof that the cult of these saints was popular among the inhabitants of Strumica and of special importance to the town of Strumica.[27]Over the course of centuries efforts have been made to remove the relics of these saints, and others to the seat of the Bregalnica bishopric. This was considered unacceptable to the people of Strumica, but a compromise was reached in the ninth century[28] whereby the people of Strumica gave up the relics of just three of the fifteen martyrs. Other attempts to transfer the relics were made in later periods. These were only partly successful. Some authors in the past have given names to the martyrs. It is, however, difficult to find any reference to these martyrs in generally available literature, which is an indication that the saints are only venerated locally in the Strumica/Bregalnica region.[29]

Hardly any information is available regarding the people, situation or circumstances in the ancient region now known as Struga or Bregalnica. But the discovery of a relatively large number of old basilicas/churches indicates that Christianity already existed on Macedonian soil in the early centuries, even in remote places.

(figures 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 from Blaga Aleksova – Loca Sactorum Macedoniae; figure 3 from Rbk V, Sv Makedonien, p. 1156)

Beckwith, p. 13 (with note 1) ↑

Beckwith, p.15 ↑

Beckwith, p. 14 (with note 3) ↑

See RbK V- Makedonien, B I a, p. 1008-1071 – Denkmäler, Architktur, Spätantike-frühbyz. Zeit, and B II a, p. 1152-1158 - Fuszbodenmosaieken ↑

Aleksova, Loca Sanctorum, p. 260/261 ↑

Aleksova, Loca Sanctorum, p. 91 ff; Kitzinger, Ernst, “A survey of the early Christian town of Stobi”, DOP 3, 1946, p. 81-162 ↑

Author’s note: it is to be remarked that the site is very difficult to find at present; there is no indication whatever on the roads. ↑

Kolarik, Ruth E., “Mosaics of the early church at Stobi”, DOP 41, 1987, p. 295-306 ↑

Balabanov, p. 12; an extensive description of this wall painting has been given by Dr. Kosta Balabanov, which is partly reproduced here with his permission, although not literally and with some alterations. ↑

Nicomedi was a town in Asia Minor (author’s note) ↑

Note Balabanov: Maximian was a co-ruler with Diocletian. It is known that with the division of the Empire, Diocletian ruled over the eastern part, which included Nicomedia, and Maximian ruled over the western part. ↑

Painter’s Manual, p.59 indicates him as an old priest with a pointed beard; RbK II, p.1077, V s.v. Hl. Ärtze, reveals that although Hermolaos is depicted in the clothing of a priest, he belongs to the Anargyroi; Müsseler, A. in LCI 5, p. 255-259, s.v. Ärzte, heilige; Boberg, J. in LCI 6, p. 511-512, s.v. Hermolaus mit Hermippus und Hermokrates; Book of Saints, p. 268, Hermolaus, an aged priest of Nicomedia, having succeeded in converting St. Panteleimon, the imperial physician, was martyred with him and with the two brothers Hermippus and Hermocrates. ↑

Cvetković Tomašević, Gordana, “Sur la chronologie des mosaïques de pavement du milieu du Ve s. jusque’ a la fin du VIe s.”, Actes du XVe Congrès International d’Études Byzantines, Athènes-Septembre 1976, Vol II, p. 807-822, considers the greater part of the Heraclea mosaics as representations of the micro-cosmos, and the trees, the flowers and the birds as a Christian paradise. ↑

Maguire, Henry, Earth and Ocean, the Terrestrial World in Early Byzantine Art, Urbana, Illinois, 1987, p. 36-40, s.v. ’The large basilica at Heraklea Lynkestis’ ↑

ibid, p. 37 ↑

ibid (with note 45) ↑

Aleksova, Loca Sanctorum, p. 177 ff ↑

Cadmus was the brother of Europa, who was abducted by Zeus in the shape of a bull. ↑

From the author’s own observations during the spring of 2002. The excavations were too recent for publication at that moment. ↑

Aleksova, Loca Sactorum, p. 223 ff ↑

Aleksova, Blaga and Mango, Cyril, “Bargala: a preliminary report”, DOP 25, 1971, p. 265-281; Aleksova, Loca Sanctorum, p. 132 ff ↑

Aleksova and Mango, p. 266 with note ↑

ibid, p. 273 and 277 ↑

Aleksova, Loca Sanctorum, p. 229 ff ↑

Grozdanov, Cvetan, Portraits of Saints in Macedonia from the 9th to the 18th Centuries, Skopje, 1983, p.93-96 (in the Macedonian language); Balabanov, p. 29ff. ↑

Angold, Michael, Church and Society in Byzantium under the Comneni 1081-1261, Cambridge 1995, p. 158-172, s.v. Theophylact of Ohrid ↑

Balabanov, p. 29-30. ↑

Balabanov, p. 30 ↑

Aleksova, Blaga and Mango, Cyril, “Bargala, a preliminary report”, DOP 25, 1971; they mention in the appendix (p.278-281) to their report 40 sites where medieval churches in the Bregalnica region can be found. ↑